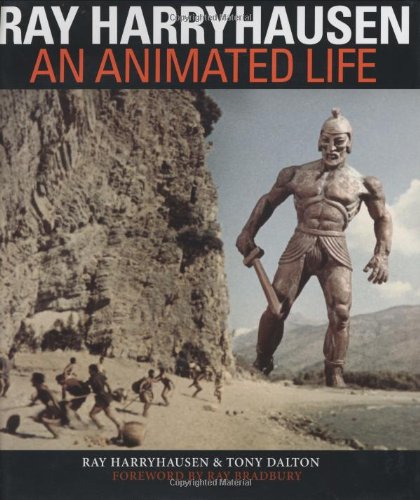

Ray Harryhausen and his films probably appeared on the cover of Cinefantastique more than any other person in the history of the magazine, so I thought it would be nice to update CFQ’s extensive past coverage of Harryhausen’s career with this interview which covers three of Ray’s recent projects: his two beautifully illustrated volumes from Billboard Books, written with Tony Dalton, An Animated Life and The Art of Ray Harryhausen, as well as his fabulous collection of shorts and fairy tales, Ray Harryhausen – The Early Years.

Ray Harryhausen and his films probably appeared on the cover of Cinefantastique more than any other person in the history of the magazine, so I thought it would be nice to update CFQ’s extensive past coverage of Harryhausen’s career with this interview which covers three of Ray’s recent projects: his two beautifully illustrated volumes from Billboard Books, written with Tony Dalton, An Animated Life and The Art of Ray Harryhausen, as well as his fabulous collection of shorts and fairy tales, Ray Harryhausen – The Early Years.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: After years of keeping your effects secrets under wraps, what led you to be so forthcoming in your autobiography of your work in movies, An Animated Life?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: I bare my soul in the book, don’t I? Everybody else is baring his soul, so I thought I might as well do it, too. You never know when the world may be coming to an end. A comet could hit the earth.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Since you actually started working on the book before the millennium, was that also a factor?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: You could put it that way. But I think it’s always been a mistake to tell people how things are done, because then it’s no longer attractive for them. So in the Film Fantasy Scrapbook I didn’t want to talk about the details—that was the point. Half the charm when I first saw KING KONG was I didn’t know how it was done. There were no books available at that time on stop-motion. In fact they tried to hide that stop-motion was a single frame process. I knew it wasn’t a man in a suit, but it wasn’t until later on that I discovered the glories of stop-motion. But nowadays everybody tells you everything about the picture before it’s released and I think it spoils everything. It allows you to start picking the scenes apart.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: That’s true, because if you didn’t know that Todd Armstrong’s voice was dubbed in JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS, you’d never give it a thought. But when you know his voice is dubbed, it becomes much more noticeably, even though it’s dubbed very well.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, we had some very good dubbing for Jason, but the reason for that was because Todd Armstrong’s American accent was a little too strong for all the British accents we had in the picture. So we got an actor (Tim Turner) who narrated a British TV series, A Look at Life to do the voice of Jason. Did you know we also had to dub Gia Golan’s voice in THE VALLEY OF GWANGI?

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Really?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, she was from Poland and we found she had a rather thick European accent, so we got another actress to dub her voice.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: How did you work with Tony Dalton in writing the book?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: After doing the Film Fantasy Scrapbook way back in 1972, I started doing this one on my own, but as I wrote it I found I was saying the same things over and over again, so I thought, “I better get somebody else in to help me.” So Tony Dalton and I sat down and discussed things, and we went through the archives and did a lot of research. During that whole process I remembered a lot of things I had forgotten about.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: It’s nice that you can remember everything in so much detail, because you joke about not even being able to remember what happened to you last week.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, but luckily some of the films are more vivid in my mind than what happened to me last week.

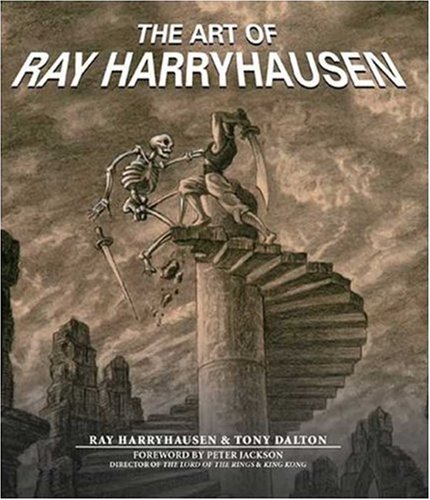

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Your second Billboard book, The Art of Ray Harryhausen, focuses on all of your pre-production drawings, storyboards, models and bronzes, which are all quite beautifully reproduced.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Your second Billboard book, The Art of Ray Harryhausen, focuses on all of your pre-production drawings, storyboards, models and bronzes, which are all quite beautifully reproduced.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, after Tony Dalton and I went through the archives, we found we had so much material we decided we could make two or three volumes, and since it’s a companion volume to An Animated Life we wanted to keep it in a similar format. Now, after doing the second book, we found we still have so many extra pictures, that we’re going to be doing a third book, but it won’t be out for a couple of years. It will be a history of stop-motion animation.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: I imagine you were a big movie fan when you were growing up.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Oh, yes. My parents were great cinemagoers and they took me to the theater when I was very young. I remember seeing the first THE LOST WORLD that Willis O’Brien made and I must have been sitting on my dad’s knee, because I couldn’t have been more than five years old. And I saw many other silent films, like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Siegfried’s Death. Then, later on in the forties, I remember all the Maria Montez pictures – Arabian Nights and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, with Jon Hall and Turhan Bey. But those pictures always left the fantasy elements out. The only one that brought the fantasy elements in was Alexander Korda’s Thief of Bagdad, which was a superb film. So I vowed then and there that every picture I made would stress the fantasy, rather than the gold hunt, or the cops and robbers and those kinds of things.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Of course, as you say in the book, in 1933 you saw the picture that changed your life.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, that’s when I first saw KING KONG. I was only 13 years old and I came out of the theater absolutely amazed. It just goes to show you how much a film can impress a young person. It really did change my life—I haven’t been the same since. It was at Grauman’s Chinese theater in Hollywood, with all the glamorous showmanship they used to put on back then for the opening of a picture. The forecourt was decorated in a jungle setting and they had a full size bust of Kong himself in the forecourt, with pink flamingos roaming around pecking at the sand beneath him. Later on, after KING KONG had made such a big impression on me, on the weekends Ray Bradbury, Forry Ackerman and I used to go down to the old Pathé lot in Culver City. You could still see the standing set of the of the Skull Island wall from the street, so we’d all look up at the wall and chant, “Kong, Kong, Kong.”

Ray Harrhausen, Lawrence French & Phil Tippet

LAWRENCE FRENCH: When you first began to pursue stop-motion animation, how supportive were your mother and father?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: My parents were very supportive, which was very important to me, because there was no information about stop-motion when I started out and there was no career to go into. But my parents always encouraged me. They helped me when I started my first 16mm experiments, when I began making the Mother Goose stories in my garage. I was very lucky that my mother also happened to be very talented with a needle and thread, so she did all the costumes and my father built all the armatures for my early shorts.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: So your first short films were a real family affair.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, and on the credits it looks like I had a big crew, but that’s because I used my Mother’s maiden name, Reske, and my Grandmothers maiden name, Blasauf, since I thought we couldn’t have all these Harryhausen’s in the credits. Today I wouldn’t be worried about that, but in those days I was more modest. So my parents were credited as Martha Reske and Fred Blasauf. And the photographer was credited as Jerome Wray, who was me.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: It isn’t hard to figure out why you billed yourself as Wray, but why the Jerome?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: The Jerome came from Jerome, Arizona, where my uncle owned a gold mine, but unfortunately it petered out.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: So the name was certainly appropriate for King Midas. When you started making feature films, your father continued to make most of the armatures for your puppets, didn’t he?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, I was very fortunate that my father happened to be a machinist, so he made all the armatures for me. I didn’t have the patience to do the lathe work myself, so I farmed it out to my dad. We had a real challenge in doing the skeletons for JASON AND THE ARGONAUTS, because we had to hide the armature within the skeletons. We finally ended up mixing cotton soaked with liquid latex and we built up the bone structure directly onto the metal armatures. The skeleton’s heads were made of plastic resin. Later on, after I lost the original swords we had made for the skeletons, I was in Madrid and I happened to find these wonderful miniature swords for spearing pickles and olives, so the sword you now see the skeleton holding is really a pickle fork.

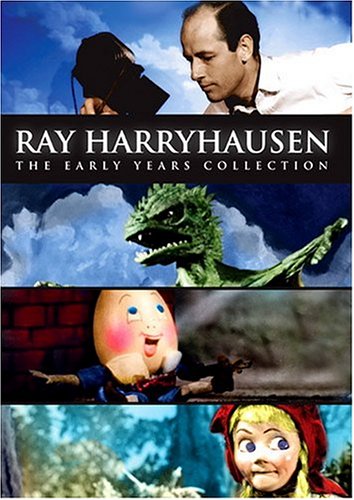

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Your new collection of shorts Ray Harryhausen – The Early Years (on Sparkhill DVD) is really the missing link in your career, because most of these shorts have never been seen before.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, the fairy tales had only been shown in schools in the early days of visual education and nobody has seen them outside of elementary schools. There have been pirated copies, but on the new DVD we have all the originals, while the pirated copies are usually dupes of dupes. So I hope nobody continues to buy the pirated copies. Most of the material was stored at my house in Malibu, but not in good conditions, so thank heavens the Academy Archive restored it all. I had originally shot everything in 16mm, and the Academy blew it up to 35mm. Arnold Kunert approached the Academy and then Scott MacQueen (who heads Disney’s restoration dept.) started the whole process rolling. We finally got the Academy to acknowledge that these fairy tales were quite important and they eventually funded the whole project. Mark Toscano at the Academy did a wonderful job. At the end of the DVD we put The Tortoise and the Hare, so now there are six fairy tales. They were mostly taken from the realm of Grimm’s fairy tales. I started making them after I began doing my early tests and experiments, because I wanted to do a story that actually had a beginning, a middle and an end. I’m very grateful they’ve been restored, because they were shot over fifty years ago, so naturally the color was slightly faded. Now, they look like they could have been made yesterday.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, the fairy tales had only been shown in schools in the early days of visual education and nobody has seen them outside of elementary schools. There have been pirated copies, but on the new DVD we have all the originals, while the pirated copies are usually dupes of dupes. So I hope nobody continues to buy the pirated copies. Most of the material was stored at my house in Malibu, but not in good conditions, so thank heavens the Academy Archive restored it all. I had originally shot everything in 16mm, and the Academy blew it up to 35mm. Arnold Kunert approached the Academy and then Scott MacQueen (who heads Disney’s restoration dept.) started the whole process rolling. We finally got the Academy to acknowledge that these fairy tales were quite important and they eventually funded the whole project. Mark Toscano at the Academy did a wonderful job. At the end of the DVD we put The Tortoise and the Hare, so now there are six fairy tales. They were mostly taken from the realm of Grimm’s fairy tales. I started making them after I began doing my early tests and experiments, because I wanted to do a story that actually had a beginning, a middle and an end. I’m very grateful they’ve been restored, because they were shot over fifty years ago, so naturally the color was slightly faded. Now, they look like they could have been made yesterday.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: What’s amazing is if you did make them today they’d probably cost over $100,000.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: I know it. But I financed them all myself. I had different jobs, and I shot them in my garage during my spare time. Sometimes on the weekends I would work all day on them, but it was mostly done in the evenings. I stayed up until two in the morning sometimes. It varied, but they took me about three or four months to finish each one, depending on how complicated they were.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: The wolf in Little Red Riding Hood was designed and animated so beautifully, it’s too bad you never did a werewolf movie.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: That gets into the category of a horror film and we never made a horror film. We made creatures, not monsters. I made the wolf a semi-werewolf, but not totally. I wanted to have a dramatic ending where he stands up and leaps over the banister before the hunter shoots him. But the original story of Little Red Riding Hood is quite lascivious and bloody, so I had to modify it. The wolf ate both Grandma and Little Red Riding Hood before the hunter splits open his stomach and frees them. You couldn’t show that back in those days, although you probably could today.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Although you never made a horror film, you liked the classic monsters movies, like DRACULA and THE WOLF MAN, didn’t you?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Oh, yes I grew up on all those wonderful pictures, like DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE, FRANKENSTEIN, and THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN. I love horror stories. I think war stories are more of a horror story than some of the horror movies that were made in the thirties.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: I imagine you also had to tone down some of the elements in Hansel and Gretel.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Yes, we had problems with the stepmother, who was very cruel in the original story. There were so many broken families, I thought we should write her out. So I had to change the story around to make it look less evil for stepmother’s.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: How did you come up with the effect for making the gingerbread house materialize?

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: I had to dream that up by myself. There were no books to consult at the time, so you had to use your imagination. I shot falling pieces of glitter photographed at high speed against black velvet, then wound the film back and combined that with the house materializing through dissolves and double exposures. It was all done in the camera, and everything was done on the first take.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: It’s such a wondrous effect.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Beam me up Scottie! I guess they copied that for STAR TREK. But you couldn’t beam up a gingerbread house (laughter). I made the gingerbread house out of real gingerbread and candy and I had it stored in my garage for two years until some mice ate it up.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Maybe it was Mickey and Minnie visiting you from Burbank.

RAY HARRYHAUSEN: Well if was, they got a free meal, because I used real cookies and candy to make it.

[serialposts]

3 Replies to “The Art of Ray Harryhausen: Interview, Part 1”

Comments are closed.