SALEM, WGN America’s historical horror television series, comes across in its initial episodes as an unholy hybrid of THE CRUCIBLE and THE SCARLET LETTER, lacking the sophistication of either, but with just enough dramatic interest to hold attention. Moody and sinister, with eruptions of sex and gore (apparently obligatory on cable series these days), SALEM is effectively horrifying at times and occasionally compelling soap opera entertainment, if one can overlook the egregious liberties it takes with the historical record it pretends to depict. However, those disturbed by the show’s assault on the truth, which often plays like pandering to the fever dreams of the religious right, will find much to fuel their outrage.

As envisioned by creators and executive producers Brannona Braga (STAR TREK: THE NEXT GENERATION) and Adam Simon (THE HAUNTING IN CONNECTICUT), the Salem Witch Trials were not merely the product of superstition, ignorance, and Puritan fanaticism; there really were witches, seeking to get a toehold in the New World and make it their own. Religious ravings about a Satanic war for the soul of Salem turn out to be accurate, though the fanatics espousing the views are corrupt and vile in their own right. Meanwhile, the secret coven members, far from persecuted innocents, are devious conspirators, manipulating the witch hunts to advance their own agenda, using their powers to target victims who stand in their way.

With this “plague on both your houses” setup, there would be little rooting interest if not for the presence of John Alden (Shane West), a soldier return from war to find Salem in the midst of hysteria and hangings. Agnostic, at least initially, on the subject of witches, Alden is tagged as the good guy by virtue of a sensibility that sounds more appropriate to the 21st century than to 1692 Salem.

On the other side of the aisle is Mary Sibley (Janet Montgomery), who was in love with Alden before he left for war. Since then, she aborted his unborn child with the aide of her Mephistophelean servant girl Tituba (Ashley Madekwe); in exchange for the rendered service, Mary has surrendered her soul and now presides as the head of the coven. Also, she has married former nemesis George Sibley, who is now a mute and paralyzed wreck of a man, involuntarily allowing Mary to wield his considerable political power to her own ends.

SALEM’s dramatic tension flows from the relationship between Mary Sibley and John Alden, who still love each other but now find themselves antagonists (though Alden is initially unaware of this). Though eager to crush her enemies and see her coven take over Salem, Mary yearns for John and sometimes contorts her plans to avoid hurting him. Alden, meanwhile, seeks her help because of the power she wields, gradually realizing that her intervention is counter-productive.

Also on hand is witch hunter Cotton Mather (Seth Gabel), who resolutely believes in his purpose, though occasionally he doubts whether those he has hanged were truly guilty. In a sense, Mather and Mary are the true warring parties in SALEM, with Alden caught in the middle, at various times forming alliances with either of them as he tries to stop the rising hysteria.

The problem with SALEM lies in its confused point of view on the subject of witchcraft and witch-hunting. Witch-hunters, whom we should rightly regard as at least misguided, turn out to be correct in their basic belief, even if their methods are faulty. The witches are even worse, if not in an absolute moral sense, then at least in their ability to do harm.

To some extent we are supposed to sympathize with Mary Sibley, because she was driven to her fateful decision by the patriarchal social order that would have condemned her, had she brought her unwed pregnancy to term. We can almost see witchcraft as the shadowy alter ego to the Puritanism of the Salem elders – an outgrowth they have unwittingly brought into existence by their belief in it. Unfortunately, the existence of Tituba and other witches, even before Mary went to the Dark Side, undermines this interpretation, validating the fears of the Puritans.

Typical for contemporary horror, Evil is portrayed as a real, supernatural force, but there is no counteracting supernatural force for Good. (As Chris MacNeil noted in THE EXORCIST, it seems the Devil keeps a higher profile.) SALEM is somewhat cagey about the exact nature of the sorcery on display; some of it could be hypnosis or hallucinations, perhaps psychic power erroneously designated as Satanic. Whatever the source, it is definitely used as Black Magic, resulting in the deaths of innocent victims.

There is an unpleasantly reactionary attitude in the show’s depiction of “Evil,” which often seems to be associated with lesbian sexuality. Mary’s abortion, with Tituba rubbing oil on her skin and lips, plays out with orgasmic intensity; shots and staging often emphasize the intimacy between the two women, and a later ritual involves a large black phallus. Charitably, one might assume that these images are intended to tweak viewer sensibility, to make us identify with the sensuous females as opposed to the uptight males running Salem. More likely, they included as gratuitous exploitation, serving to excite prurient interest while simultaneous conforming to a conservative view that non-traditional gender roles lead inevitably to damnation.

Unlike Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, which understood both the benefits and harm in Puritanism, SALEM is one-dimensional in its depiction. Even the occasional apparent voice of reason turns out to be a hypocrite or, worse, an agent of the Devil. The result pushes the show in the exact opposite direction of Miller’s THE CRUCIBLE, which sought to condemn witch-hunting hysteria. Here, the message seems to be: all those not for us are against us, and someone expressing an interest in finding the middle ground is probably an enemy in sheep’s clothing.

Fortunately, the show manages to maintain interest thanks to its depiction of innocents caught in the crossfire. The situation is not dissimilar from that seen in Hammer Films’ TWINS OF EVIL (1971), which also showcased religious fanatics in a spiritual war with genuine supernatural evil. That film resolved its dilemma thanks to an agnostic but educated protagonist, who managed to find a middle ground that exonerated the innocent while dispatching the guilty. John Alden has been set up in a similar role. Hopefully, as the show progresses, he can rise to the occasion and find some way out of the sordid sorcery and morbid melodrama plaguing SALEM.

SALEM (WGN America, debut on April 20, 2014). Created by Executive Producers Adam Simon and Brannon Braga. Cast: Joanet Montgomery, Shane West, Seth Gabel, Tamzin Merchant, Ashley Madekwe, Elise Eberle, Xander Berkeley, Iddo Goldberg, Stephen Lang.

[serialposts]

Tag: witches

Cinefantastique's Greatest Movie Cheats: Rosemary's Baby

Hello, fellow movie cheaters! Hm, maybe that’s not the best way to describe fans of movie cheats, but it has a nice ring to it. In any case, I am back with another in an on-going series of the greatest movie cheats in horror, fantasy, and science fiction films. This one is a real gem – and long overlooked (even by me, who is deliberately searching for this kind of thing).

Please recall our definition of a “cheat,” which is a variation on movie terminology used when a prop or set piece is moved from its established position in order to create a more pleasing composition on screen (that is, when you move the camera to a new angle, you “cheat” lamp in the background to the left or right, so that it doesn’t seem to jump from one side of the character to another when the shots are cut together). In our usage, a “cheat” is a piece of cinematic sleight-of-hand that pulls a fast one on the audience, often violating the film’s own internal “reality.” Usually, a cheat works because the trickery is visible, though perhaps subliminal; if you couldn’t see it, the impact would be lost.

Writer-director Roman Polanksi’s 1968 film ROSEMARY’S BABY – based on Ira Levin’s novel, about a young married woman who believes her unborn child has been targeted for sacrifice by Satanists – is generally considered to be one of the great achievements in the horror genre – a subtle exercise in suspense that works because it remains grounded in the real world, its horrors suggested and ambiguous, its supernatural element possibly imagined. What has never been mentioned before (at least until it was pointed out to me*) is that the film features a remarkable movie cheat – one that may be unique. Before we get to the cheat, however, we have to take a look at the set-up.

Midway through the film, before the suspense has set in, the recently pregnant Rosemary (Mia Farrow) attends a party, where she chats with pediatrician Dr. Abraham Sapirstein (Ralph Bellamy). In this scene, Dr. Sapirstein is photographed only from behind; in fact, it is hard to say with certainty whether we are seeing Bellamy or a body double with Bellamy’s voice dubbed in. Whatever the case may be, we get a good look at the back of Sapirstein’s head – enough to recognize the doctor from behind later in the movie.

This recognition takes place during a four-minute sequence during which Rosemary, convinced that Dr. Sapirstein is part of the Satanic conspiracy, uses a phone booth to contact her old pediatrician, begging him to see her. While Rosemary is facing toward camera, her back to the phone booth door, a man slides into view; the audience immediately “knows” it is Dr. Sapirstein.

Finishing her call, Rosemary turns and pauses in alarm when she sees the man. She closes her eyes in fear and desperation; when she opens them again, she is relieved to see that the man has turned around revealing not Dr. Sapirstein but just someone wanting to use the phone (a cameo by producer William Castle).

The scene is deceptively simple: a single, continuous take in close-up, with only a short camera move to emphasize the appearance of the man waiting outside the phone booth. But there is more here than meets the eyes – at least the eyes of the character. I have deliberately omitted a few frames in order to convey what Rosemary perceives, which might also represent the erroneous impression that a viewer could take away from the film: that there was a man who looked like Dr. Sapirstein from behind, but he turned around to reveal an unexpectedly innocent face.

What Rosemary does not notice is that, while her eyes are closed, the “Sapirstein” character walks off-screen, then walks back into the shot – or does he? It may not be apparent on first viewing, but if you go back and look again, the switch takes place a little too quickly for the man to have walked away, done a 180-degree turnabout, and come back.

Instead, this is what seems to happen:

After Mia Farrow closes here eyes, Bellamy (or his body double) exits to the left.

For a brief moment the “Sapirstein” character is off-screen, while Farrow plays Rosemary as if she is silently praying for deliverance.

The “Sapirstein” character appears to re-enter the frame – actually William Castle. It is hard to tell from the brief glimpse we get, but if you pause the film and look carefully, Castle’s hair does not quite match the back of Dr. Sapirstein’s head, confirming that a switch has been made.

As she opens her eyes, Farrow is blocking our view of the actor outside the booth, making it difficult to notice the switch that has taken place. When she finally turns, the movement of her head reveals not Bellamy’s Dr. Saperstein but the smiling stranger played by Castle.

What makes this cheat uniquely interesting is that it may not be a cheat at all. On a superficial level, the gag is that Rosemary and the audience think the man outside the booth is the sinister Dr. Sapirstein, but he turns out to be someone totally innocuous; the “cheat” is achieved by simply having Castle quickly replace the other actor. However, the switch takes place in full view of the camera, leaving the scene open to a second interpretation: that we are supposed to notice the switch, even if Rosemary does not; although we sympathize with her relief when she re-opens her eyes, we have to wonder whether she was right the first time: maybe that was Dr. Sapirstein, and he has simply gone off to alert the other Satanists that he has located Rosemary. In which case, the “cheat” of using Bellamy (or his double) to fool us into “seeing” Sapirstein is not a cheat at all but rather an accurate depiction of what happens in the scene.

There is a delicious ambiguity to this interpretation: Was it, or was it not, Sapirstein? Was it, or was it not, a cheat? And on a meta-level, was it, or was it not, Bellamy’s body double in either or both scenes?

As intriguing as these questions are, there is yet a third, equally intriguing interpretation of the scene. As much as ROSEMARY’S BABY is a story of witches, Satanists, and the Anti-Christ, the film is also a study in paranoia, with Rosemary driven to hysteria by fear for her baby. In the phone booth scene, she thinks Dr. Sapirstein has found her. She closes her eyes as if wishing him away, and it works: when opens her eyes, he is gone – like magic. What we may be seeing in the shot is an externalization of Rosemary’s inner mental state: her fear manifests as the appearance of Dr. Sapirstein; the appearance of the harmless stranger represents a return to a semblance of normalcy, a momentary quelling of paranoia, as Rosemary briefly gets a grip on her emotions that have been driven to extremes by both the events around her and the hormonal changes inside her body. In which case, we’re back to calling the scene a movie cheat, because two actors were switched right before our eyes to create an erroneous impression. The difference is that, in this new interpretation, the switch conveys not a mistaken identity but a paranoid delusion.

That’s an impressive amount of significance and meaning to pack into a single shot, making this scene worth a second look not only to spot a great movie cheat but also to appreciate the subtle tour-de-force machinations of a master filmmaker at work.

Note: This article has been updated to explain our definition of movie cheats, in order to clarify that it is not a derogatory term.

FOOTNOTE:

- A tip of the hat to Ted Newsom for pointing out this overlooked movie cheat.

[serialposts]

The CW's 'Secret Circle'

The CW announced its Fall schedule, with just one new genre show, the “teenage witch” drama THE SECRET CIRCLE.

THE SECRET CIRCLE will join THE VAMPIRE DIARIES on THURSDAYS, while spy-fi series NIKITA will take the departed SMALLVILLE’s Friday 8:00 PM slot, before the returning SUPERNATURAL.

THE SECRET CIRCLE – “Cassie Blake was a happy, normal teenage girl – until her mother Amelia dies in what appears to be a tragic accidental fire. Orphaned and deeply saddened, Cassie moves in with her warm and loving grandmother Jane in the beautiful small town of Chance Harbor, Washington — the town her mother left so many years before—where the residents seem to know more about Cassie than she does about herself.

As Cassie gets to know her high school classmates, including sweet-natured Diana and her handsome boyfriend Adam, brooding loner Nick, mean-girl Faye and her sidekick Melissa, strange and frightening things begin to happen. When her new friends explain that they are all descended from powerful witches, and they’ve been waiting for Cassie to join them and complete a new generation of the Secret Circle, Cassie refuses to believe them—until Adam shows her how to unlock her incredible magical powers. But it’s not until Cassie discovers a message from her mother in an old leather-bound book of spells hidden in her mother’s childhood bedroom, that she understands her true and dangerous destiny.

What Cassie and the others don’t yet know is that darker powers are at play, powers that might be linked to the adults in the town, including Diana’s father and Faye’s mother—and that Cassie’s mother’s death might not have been an accident.

The series stars Britt Robertson as Cassie Blake, Thomas Dekker as Adam Conant, Gale Harold as Charles Meade, Phoebe Tonkin as Fay Chamberlain, Jessica Parker Kennedy as Melissa, Shelley Hennig as Diana Meade, Louis Hunter as Nick, Ashley Crow as Jane Blake and Natasha Henstridge as Dawn Chamberlain.

Based upon the book series by L.J. Smith (author of The Vampire Diaries book series), THE SECRET CIRCLE is from Outerbanks Entertainment and Alloy Entertainment in association with Warner Bros. Television and CBS Television Studios with executive producers Kevin Williamson (The Vampire Diaries, Scream, Dawson’s Creek), Andrew Miller (Imaginary Bitches), Leslie Morgenstein (The Vampire Diaries, Gossip Girl) and Gina Girolamo. Elizabeth Craft (The Vampire Diaries, Lie to Me) & Sarah Fain (The Vampire Diaries, Lie to Me) were executive producers on the pilot which was directed by Liz Friedlander (The Vampire Diaries, 90210).”

'Season of the Witch' — Trailer

Opening tomorrow, January 7th is the medieval supernatural action thriller SEASON OF THE WITCH.

” Nicolas Cage (‘National Treasure’, ‘Ghost Rider’) and Ron Perlman (‘Hellboy’, ‘Hellboy II’) star in this tale of a 14th century Crusader who returns to a homeland devastated by the Black Plague. A beleaguered church, deeming sorcery the culprit of the plague, commands the two knights (Nicloas Cage, Ron Perlman) to transport an accused witch to a remote abbey, where monks will perform a ritual in hopes of ending the pestilence.

A priest, a grieving knight, a disgraced itinerant and a headstrong youth who can only dream of becoming a knight join a mission troubled by mythically hostile wilderness and fierce contention over the fate of the girl. When the embattled party arrives at the abbey, a horrific discovery jeopardises the knight’s pledge to ensure the girl fair treatment, and pits them against an inexplicably powerful and destructive force.”

Directed by Dominic Sena (KALIFORNIA) from a screenplay by Bragi F. Schut (THRESHOLD) , SEASON OF THE WITCH also stars Claire Foy, Stephen Campbell Moore, and Robbie Sheehan. Fan favorite Christopher Lee also appears.

From Relativity Media

Ultra Maniac, Fantasy Anime Online

Viz Media tells us that ULTRA MANIAC debuts today on iTunes, Hulu, and VIZAnime.com

Viz Media tells us that ULTRA MANIAC debuts today on iTunes, Hulu, and VIZAnime.com

ULTRA MANIAC is based on the shojo manga of the same name also published by VIZ Media.

The popular Ayu meets transfer student Nina, who’s got a bit of an odd personality. They become fast friends though, and Ayu soon discovers Nina’s secret – she’s a witch that came from the Kingdom of Magic to study abroad!

Episodes of the first part of season one (13 episodes total) will be available Download-To-Own from iTunes for $1.99 each and Download-To-Rent for $0.99 each; season one part two will be available beginning December 6th.

As a enticement, VIZ is making Episode 1 is available to download for FREE until November 23rd!

VIZAnime.com and Hulu will both be streaming episodes 1-5 for free, and 2 new episodes will launch each Monday.

Inferno (1980) on DVD

This film is a fascinating and frustrating phantasmagoria of the mysterious and the unexplained, a strange journey into realms beyond human understanding, where events happen without rhyme or reason, and little or no explanation is given. Although framed as a conventional horror film (with a protagonists searching for the secret of an evil power lurking in an old building), INFERNO borders on the surreal in its approach. The casual disregard for narrative logic, for the laws of cause and effect, recall Luis Bunuel at his most anarchic; the stylized beauty of the imaginative imagery is reminiscent of Jean Cocteau. However, as an experiment in “Absolute Cinema,” in which form overrules content, INFERNO cannot be reckoned a total success. The combination of the beautiful and the bizarre is hypnotically entertaining, but imagery does not resonate quite deeply enough to compensate for the lack of conventional virtue.

At times the storyline feels simply empty rather than esoteric, and one wishes that more effort had been put into making sense of the whole thing. The saving grace is the lingering suspicion that somewhere, tantalizingly out of reach, just beyond the edge of awareness, is an answer to the mystery. Whether or not this is actually true, INFERNO feels like an intriguing enigma, one that holds interest precisely because it withholds any definite resolution.

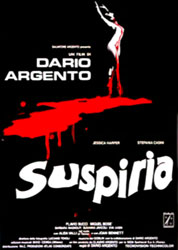

Writer-director Dario Argento had been plying his trade, making horrific psycho-thrillers (known as giallo in his native Italy) since the early ‘70s, reaching his peak with Deep Red in 1975. Then he took a turn into supernatural horror with Suspiria in 1977 and scored his biggest hit in the United States, where it was released by 20th Century Fox (under a subsidiary label). The financial success prompted this 1980 sequel of sorts, which, unfortunately, failed to equal the financial success of the original. Although the film is much less well-known in the U.S. than its progenitor, it is a worthy follow-up that in some ways exceeds the original, even if it is nowhere near as satisfying on a visceral level.

INFERNO tends to disappoint fans of Suspiria – the Argento film for most North American horror audiences. That effort took the visual extravagance of Deep Red and magnified it to an even greater degree, casting aside the psycho-thriller trappings in favor of an Gothic spook show (actually, Baroque would be a better term, considering the architecture on display). Having distilled the story down to a bare minimum, Argento sustained Suspiria on style, and he pretty much succeeded, with shock effects that went way, way over the top. However, the film was unevenly paced, and the Grimm Fairy tale trappings were less deeply disturbing than the psychological horrors of his previous work.

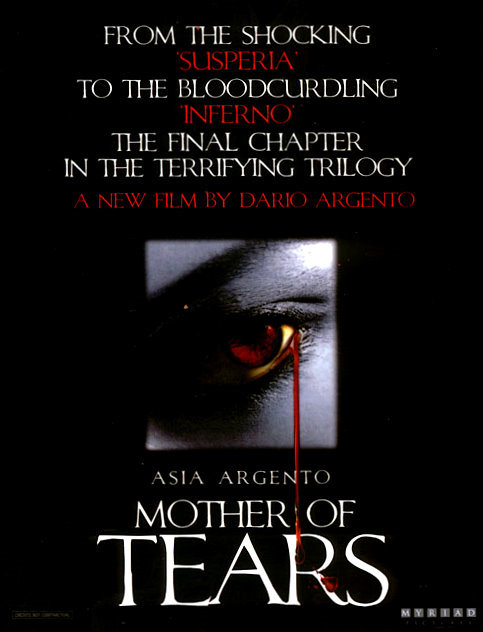

For INFERNO, Argento crafted a sort of indirect sequel, with no continuing characters. Instead, he sets up a mythology regarding the “Three Mothers,” immortal supernatural beings who control mankind’s destiny, sowing destruction, death, and sorrow. The connection between the two films is revealed when a student named Rose (Irene Miracle) reads a book by an architect-alchemist known as Varelli, who designed three incredible manses, one for each of the Three Mothers: one in Germany, one in New York, and one in Rome. Having introduced the witch Helena Marcos (a.k.a. “the Mother of Sighs”) in SUSPIRIA, Argento centers the film on the “Mother of Darkness.” (The two figures were introduced in hallucinogenic essay “Levana and our Ladies of Sorrow” by Thomas De Quincy, author of “Confessions of an Opium Eater”; a third, the Mother of Tears, finally arrived in U.S. theatres in 2008.) When Rose disappears after her discovery, her brother Mark (Leigh McCloskey), who has been studying music in Rome (and briefly glimpsed a mysterious, beautiful woman – presumably, the Mother of Tears) returns to New York and searches for clues in the incredible ornate building where his sister was staying. His dream-like quest eventually brings him to a face-to-face encounter with the Mother of Darkness, but a (rather convenient) fire consumes the building, allowing him to escape, physically unharmed but with a new knowledge of dark and troubling things at work in the universe.

For INFERNO, Argento crafted a sort of indirect sequel, with no continuing characters. Instead, he sets up a mythology regarding the “Three Mothers,” immortal supernatural beings who control mankind’s destiny, sowing destruction, death, and sorrow. The connection between the two films is revealed when a student named Rose (Irene Miracle) reads a book by an architect-alchemist known as Varelli, who designed three incredible manses, one for each of the Three Mothers: one in Germany, one in New York, and one in Rome. Having introduced the witch Helena Marcos (a.k.a. “the Mother of Sighs”) in SUSPIRIA, Argento centers the film on the “Mother of Darkness.” (The two figures were introduced in hallucinogenic essay “Levana and our Ladies of Sorrow” by Thomas De Quincy, author of “Confessions of an Opium Eater”; a third, the Mother of Tears, finally arrived in U.S. theatres in 2008.) When Rose disappears after her discovery, her brother Mark (Leigh McCloskey), who has been studying music in Rome (and briefly glimpsed a mysterious, beautiful woman – presumably, the Mother of Tears) returns to New York and searches for clues in the incredible ornate building where his sister was staying. His dream-like quest eventually brings him to a face-to-face encounter with the Mother of Darkness, but a (rather convenient) fire consumes the building, allowing him to escape, physically unharmed but with a new knowledge of dark and troubling things at work in the universe.

For much of the running time, this is an amazingly restrained effort from Argento, substituting a more subtle Keith Emerson score in place of the pulverizing Goblin music used to such great effect in Suspiria. Emerson occasionally reaches for a more frenetic approach to match the horror sequences, but in general the emphasis is more on mood than shock.

Also considerably toned down is the photography. The colors are just as artificial and intentionally unbelievable, but they are no longer as garish. The effect is even mor Bava-esque than in Suspiria, which expanded on experiments by Argento’s predecessor, director-cinematographer Mario Bava, who crafted ornate lighting schemes without regard to realism.

Also considerably toned down is the photography. The colors are just as artificial and intentionally unbelievable, but they are no longer as garish. The effect is even mor Bava-esque than in Suspiria, which expanded on experiments by Argento’s predecessor, director-cinematographer Mario Bava, who crafted ornate lighting schemes without regard to realism.

In keeping with this muted approach, no single set-piece ever reaches the intensity of Suspiria’s famous opening. In fact, the gore seems trimmed way back: instead of lingering on the details and dragging them out as long as possible (his usual approach), Argento builds to climaxes and quickly fades out. (This would suggest post-production censorship, but Anchor Bay’s DVD was released with Argento’s involvement, indicating that it represents his director’s cut.) One or two moments of violence even take place entirely off-screen, to be revealed only after the fact. One might almost be tempted to use the word subtlety, but the term is make sense only in comparison to Argento’s previous work.

In at least one sense, INFERNO notably outdistances its progenitor. For all its outre formal experimentalism, Suspiria featured a conventional (and admittedly weak) narrative that followed a lead protagonists in a linear fashion and contained only a handful of murders (all of which happened for reasons that were easy to understand). INFERNO dispenses with almost any semblance of coherence; like Once Upon a Time in the West (the Sergio Leone Western for which Argento co-wrote the story), INFERNO effectively segues from set-piece to set-piece, whether or not much plot connects the individual scenes.

The overall thread of Mark’s search for his sister is clear enough, but that doesn’t stop Argento from killing off any and all peripheral characters who happen to wander into the Three Mothers’ sphere of influence. This is complicated by the fact that these wicked stepmothers do not necessarily act directly but through intermediaries, so it is not always clear who is actually perpetrating the physical violence: a demon, an acolyte, an innocent person possessed by evil? (The point is underlined by a brief montage showing a pair of hands cutting the heads of three paper dolls; each doll is followed by a cutaway to an apparently unrelated event: a lizard eating a bug, a woman committing suicide, the lights going out in the apartment of a character who has learned the truth about the Three Mothers. Though never exlained, one must conclude that the hands belong to the Mother of Tears, who uses the dolls to work her evil magic, causing long-distance death and destruction.) The effect is at once confusing and disorienting, creating a universe in which death and evil lurk ever waiting to claim the unwary, no matter how ignorant and nonthreatening they may be to the forces of darkness at work.

The overall thread of Mark’s search for his sister is clear enough, but that doesn’t stop Argento from killing off any and all peripheral characters who happen to wander into the Three Mothers’ sphere of influence. This is complicated by the fact that these wicked stepmothers do not necessarily act directly but through intermediaries, so it is not always clear who is actually perpetrating the physical violence: a demon, an acolyte, an innocent person possessed by evil? (The point is underlined by a brief montage showing a pair of hands cutting the heads of three paper dolls; each doll is followed by a cutaway to an apparently unrelated event: a lizard eating a bug, a woman committing suicide, the lights going out in the apartment of a character who has learned the truth about the Three Mothers. Though never exlained, one must conclude that the hands belong to the Mother of Tears, who uses the dolls to work her evil magic, causing long-distance death and destruction.) The effect is at once confusing and disorienting, creating a universe in which death and evil lurk ever waiting to claim the unwary, no matter how ignorant and nonthreatening they may be to the forces of darkness at work.

The result is a much smoother piece of work overall, lacking both the intense highs and the lulling lows of Suspiria. This more carefully balanced approach keeps INFERNO floating on a level altitude for most of its running time. Unfortunately, the disregard for narrative also raises suspicion that Argento has simply found a convenient rationalization for his own lack of story-telling prowess; it is almost as if an artist, who could not draw a straight line, turned to abstract art as a way of hiding his short comings. This becomes most apparent in the frankly disappointing ending: as in Hammer Films’ Plague of the Zombies, a convenient fire burns down the abode housing the villain, saving the hero from actually having to do anything. (One should also note that this non-narrative format, in which a variety of loosely connected characters are killed off for transgressing on the territory of an evil supernatural female, was distilled and perfected by Takashi Shimizu in his Ju-On films.)

Perhaps INFERNO’s most effective quality is that it is so damned cryptic! Using alchemy as his metaphor (an esoteric precursor to science meant only to be understood by its practitioners), Argento unfolds this tale, full of implied significances which are never unexplained.* The audience is left, like the film’s hero, feeling as if exposed to a dark mystery with no solution—or perhaps a solution beyond human explanation. As Argento said at an American Cinematheque retrospective of his work: “When I read about alchemy, I kept asking ‘Why?’ But there is no why!” Alchemy is all about process—that is, the journey, not the goal. That’s what Inferno is: a dark journey.

As if to belie this mysterioso approach to narrative, the DVD does reinstate one scene previously missing from American prints of the film: a brief dialogue between Rose and the bookseller from whom she bought the fateful volume that results in so many deaths. Poised like a traditional expository scene (the equivalent of Udo Kier’s brief cameo near the end of Suspiria), the vignette is really more of a “non-explanation” explanation, which really doesn’t elucidate much of anything (“..the only true mystery is that our very lives are governed by dead people”). But its appearance so early in the film at least clues viewers in to the fact that they shouldn’t be hoping for a narrative neatly tied up with explanations.

TRIVIA

Although INFERNO focuses mostly on the Mother of Darkness in New York, it features a cameo by the Mother of Tears in Rome, who shows up at a music lecture Mark is attending, complete with a white kitty cat (rather like the one Blofeld used to have in the Bond films). Later, the film drops a hint about the dwelling place of the Mother of Tears: as Sara, Mark’s fellow student, approaches the Biblioteca in Rome, she notes a sickly sweet smell – like the one Rose, Mark’s sister, noticed in her New York apartment, signaling the presence of the Mother of Darkness. However, Argento’s later MOTHER OF TEARS ignored this hint and placed the Mother of Tears in a completely different dwelling place. In retrospect, viewers must assume that the sickly sweet smell emanated from the alchemist lair into which Sara stumbles while trying to find her way out of the library.

DVD DETAILS

Denied a theatrical release (or even a handful of art house screenings) in the U.S., INFERNOmade its U.S. debut on a now out-of-print VHS tape, which provided adequate picture and sound quality, but cropped the left and right sides of the widescreen image, chopping down Argento’s carefully framed images and thus deleting much of the atmosphere. Consequently, Anchor Bay’s 2000 DVD release represented the first chance for most American viewers to see the film in something like the form its director intended.

The disc corrects this the aspect ratio with a nicely letter-boxed image (enhanced for 16X9 TV screens) and a choice of Dolby 2 channel or Dobly 5.1 sound. The soundtrack is in English only (no Italian ), which is unfortunate: English-speaking leads McCloskey and Miracle get to speak in their own voices, but the dubbing of the Italian supporting cast leaves much to be desired (check out the lame voice given to Alida Valli, who sounded so much better in Suspiria). The sumptuous colors of Romano Albani’s cinematography shine through, and Keith Emerson’s moody music is sharp and clear. Since the film’s effectiveness comes more from the interplay of visuals and music than from story, this combination is not to be underestimated: if you’ve only seen the film on video and found it disappointing, now is your chance to experience the full effect of INFERNO.

In addition to preserving the film in excellent condition, the disc also offers some relatively brief but entertaining extras: a theatrical trailer, a gallery of stills, talent bios, and a videotaped interview with Argento. The trailer captures the tantalizing quality of the film, despite probably giving away too many of the scare sequences. The stills, all in black-and-white, show a few memorable scenes from the film, plus one or two behind-the-scenes images of Argento at work—not as extensive as one would like, but not bad, either. There are three talent bios, for Argento, for his brother Claudio, who produced the film, and for Daria Nicolodi, Argento’s one-time paramour, who co-starred in INFERNO and co-writer Suspiria. The only extensive bio is for Argento, but the other two hit the main points of interest to the uninitiated; also, the bios for both Argentos benefit from the inclusion of quotes pulled from existing interviews, rendering them slightly more usual than the usual dry rundown of facts. All the bios are followed by selective filmographies.

The highlight of the disc’s extras is the interview with Argento, which is actually more of a brief, behind-the-scenes documentary, including stills, clips, and comments from Argento’s assistant director Lamberto Bava (who went on to direct the Argento-produced Demons and Demons 2.) The interview is presented with the subjects speaking in their native language, and viewers have the choice of watching with or without English subtitles.

Fans of Lamberto’s famous father, director-cinematographer Mario Bava, will be pleased to see that the elder Bava’s uncredited (but always acknowledged) contribution to INFERNO have finally been clarified here. Rumors have abounded that Mario Bava directed the film’s underwater sequence (a genuinely creepy standout), but in truth it was his skill as a cinemagician that was put to use. Although set mostly in New York, Inferno was filmed mostly in Italy. It was Mario Bava who supervised the composite shots that put New York skylines outside windows and in the background of an interior set simulating Central Park. He also contributed a few more noticeable special effects, such as the Mother of Darkness’s disappearance (exactly like a similar scene in Bava’s directorial debut Black Sunday) and reappearance in skeletal form after bursting out from inside a mirror.

Fans of Lamberto’s famous father, director-cinematographer Mario Bava, will be pleased to see that the elder Bava’s uncredited (but always acknowledged) contribution to INFERNO have finally been clarified here. Rumors have abounded that Mario Bava directed the film’s underwater sequence (a genuinely creepy standout), but in truth it was his skill as a cinemagician that was put to use. Although set mostly in New York, Inferno was filmed mostly in Italy. It was Mario Bava who supervised the composite shots that put New York skylines outside windows and in the background of an interior set simulating Central Park. He also contributed a few more noticeable special effects, such as the Mother of Darkness’s disappearance (exactly like a similar scene in Bava’s directorial debut Black Sunday) and reappearance in skeletal form after bursting out from inside a mirror.

The original DVD release also included a four-page booklet that listed the Chapter Selections and contained a brief interview with Leigh McCloskey, who discusses Argento’s enigmatic approach to directing actors and relates how the actor filled in for his stuntman during the film’s fiery conclusion.

CONCLUSION

Although INFERNO will probably never replace Suspiriain the hearts of many fans, it is an effective horror film that mixes graphic violence with narrative ellipses in an intriguing way that prefigures the work of Lucio Fulci (The Beyond) and Takashi Shimizu (Ju-On: The Grudge). For those wanting easily understandable stories and/or fast-paced shocks, this film may not be for you, but if you are willing to enter a magical sinister world where mysterious things happen for little or no apparent reason, you may find yourself swept up in a nightmarish landscape such as few films have ever created. And there’s always something to be said for a film that studious eschews the oft-repeated admonition of most horror films: “There’s got to be a rational explanation!”

No, there doesn’t. And this film is the better for it.

INFERNO (1980). Written and directed by Dario Argento. Cast: Leigh McCloskey, Irene Miracle, Eleonora Giorgi, Daria Nicolodi, Sacha Pitoeff, Alida Valli, Veronica Lazar, Gabreiele Lavia, Feodor Chaliapin, Aria Pieroni.

Suspiria (1977) – A Nostalgia Review

SUSPIRIA was one of those films I missed the first time around. When it hit U.S. screens in 1977, I found the advertising campaign decidedly uninteresting; for some reason, it suggested a schlocky gore movie to me. Not that I was opposed to explicit horror: I had been sneaking into R-rated movies like THE EXORCIST since 1973, but I had to feel there was something more than just mindless mayhem to get me into the theatre. The largely negative review in Cinefantastique magazine, which called the film “hackneyed in concept, but experimental in form,” was not enough to change my mind, but it did inspire me to check out SUSPIRIA when it played on cable television. That was the beginning of my life-long love affair with the work of Dario Argento, which continues to this day, thanks to the art house release of THE THREE MOTHERS this weekend.

In retrospect, I was of the perfect age and temperment to enjoy Argento’s garish, overblown, and thoroughly ear-splitting horror film. A film student, I loved cinema in general, but I especially loved films that utilized the form to its fullest extent. In Argento, I saw a sort of Italian equivalent of Brian DePalma, a filmmaker eager to employ every device at his command in order to achieve an effect on the audience. Argento did not utilize any of DePalma’s split-screen tricks, but there were similar lengthy tracking shots meant to pull you psychologically into the world of the movie; there was an over-powering rock-n-roll soundtrack (by Goblin), just as there had been in DePalma’s PHANTOM OF THE PARADISE (1975); and of course, PHANTOM’s young ingenue, Jessica Harper, played the lead in SUSPIRIA.

I had little patience with people of more conventional taste, who preferred subtlety and complained that excessive technique was distracting, distancing one from the drama, reminding the viewer that he was watching a movie. For me, this was the whole point. I knew I was watching a movie, and no amount of “subtlety” (for me, a synonym for a prosaic, unimaginative style) was going to convince me otherwise. I reveled in SUSPIRIA’s artificiality, in the outrageous art direction and unbelievable lighting schemes.

From the very first reel, the taxi ride from the airport, I knew I was seeing something special, when the passing streetlights were conveyed not with alternating light and darkness but colors shifting from red to green. It was a bold gambit: immediately challenging the viewer with the obvious artificiality, announcing that what they were seeing made no pretense to verisimilitude. No, I was seeing a film in which the director had pulled out all the stops (post-SPINAL TAP, we would say he turned the amplifier up to 11), flooding the screen with sound and color – a rich, overwhelming experience that explored some of the farthest reaches of what cinema could achieve when unleashed from conventional boundaries.

From the very first reel, the taxi ride from the airport, I knew I was seeing something special, when the passing streetlights were conveyed not with alternating light and darkness but colors shifting from red to green. It was a bold gambit: immediately challenging the viewer with the obvious artificiality, announcing that what they were seeing made no pretense to verisimilitude. No, I was seeing a film in which the director had pulled out all the stops (post-SPINAL TAP, we would say he turned the amplifier up to 11), flooding the screen with sound and color – a rich, overwhelming experience that explored some of the farthest reaches of what cinema could achieve when unleashed from conventional boundaries.

One scene that particularly won me over involved the death of a blind pianist, walking home one night with his seeing-eye dog. The dog senses something, and the man cries out, “Who’s there?” For several minutes, nothing really happens. Argento builds the scene by editing back and forth between the man, his dog, and the stark facades of the buildings surrounding them, while the screeching soundtrack attempts to pulverize the audience’s nerves. The idea of extending a moment through editing was intriguing – creating a sense of anticipation not through action but through the juxtaposition of images suggesting something about to happen.

I was also amused by the way the scene quotes from the English horror film NIGHT OF THE EAGLE (known as BURN, WITCH, BURN in the U.S.). Near the end of that wonderfully suggestive film (also about witches operating in secret in an academic setting), a man outside a university sees the oversized statute of an eagle, atop the building, come to life and take flight, attacking him. In SUSPIRIA, Argento deliberately tilts up one building, revealing the statue of a gryphon. After cutting in for a closer shot, he cuts to a reverse angle, and the camera swoops down – accompanied by the fluttering of wings – upon the blind man.

The effect suggests that the statue has come to life, but subsequent long shots reveal it is still atop the building where it was first seen. Then what was that fluttering sound? What point of view was being shown as the camera swooped down? Was it some kind of invisible demonic force, somethign that resided within the statue? While I was still working out the answer to that question, the blind man’s dog turned on him and tore out his throat! I had to give Argento credit for taking me totally by surprise. The visual reference to one of my favorite films had me expecting danger from above. Little did I expect that death would come from below, not from an enemy but from man’s best friend. What an excellent piece of misdirection!

This scene was also at least partly responsible for Argento’s reputation as a filmmaker who did a poor job of handling basic story points. What did the scene contribute to the plot? In fact, why did the man die at all? Later in the film, we learn that witchcraft is afoot, and we are told that witches can use their power to destroy those who offend them, for whatever reason. The death was obviously a set piece, thrown in for its own sake, and I simply assumed the blind man had somehow or other offended the coven living in the dance academy. Only years later would I learn the specific reason.

I was not completely blown away by my first viewing of SUSPIRIA. I was – and still am – dedicated to the position that you have not really seen a movie until you have seen it in a theatre. The television experience simply could not overwhelm me in the way that the film intended to, but enough of the impact survived to make me want to see SUSPIRIA on the big screen at the earliest opportunity. Back in the days before home video had decimated the repertory theatre business, this was not an impossible dream. Not too many months passed before the film showed up at the old Cameo Theatre, a dilapidated flea pit on Broadway in Los Angeles.

The Cameo was one of many old theatres in the downtown area, but it lacked the faded elegance of the Orpheum, the Los Angeles Theatre, or the Million Dollar Theatre (the later is the one seen across the street when Sebastian meets Pris in BLADE RUNNER). These other three theatres were relic from an earlier era – movie palaces that had once offered a fashionable, luxurious cinema-going experience – before shifting demographics and changing economics turned them into de facto museums. The Cameo, I suspect, was always a dump: there were no magnificent balconies, no elaborate decor, no carved pillars, no painted murals. It was really barely one step away from being a large auditorium.

Typically, the Cameo played quadruple bills of second run movies, at discount prices. I don’t think the marquee listed the titles (you had to walk up to the box office window to see them), and there was definitely no list of screening times. I suspect that most of walk-in customers simply bought a ticket and took their chances, walking into the middle of whatever film happened to be playing.

Of course, I had called ahead to get the correct starting time. I was too cheap to pay for parking in those days, so I parked literally miles away (there were no nearby streets without parking meters) and hoofed my way over, along with a fellow film student. After buying our tickets, we entered the dark realm of the inner theatre, which gave a pretty decent impression of what the outer circles of hell must resemble: there was a foul stench, incessant rustling, dark shapes silhouetted against dim lights, and the constant murmur of lost souls. From previous experience at the Cameo, I knew that this last sound was the multi-lingual audience translating the English dialogue into their native tongues for the benefit of their non-English-speaking companions.

Then the trailers and previews finished, and SUSPIRIA began.

As fun as the film had been on television, the expanded visual and audio achieved a much more awesome impact on the big screen. Although the projection and sound quality were far from the best, the audience was completely into the movie. The artsy effects and complete lack of realism did nothing to dampen their appreciation of the horror on screen. The sound may not have been six-channel Dolby stereo, but it was louder and more pulse-bounding than it could have been from my television speaker, and it figuratively rocked the house.

The famous first murder was stunning. It must be a trick of memory or perception, but the shot of the unfortunate victim, crouched and wounded as a hand shoots into frame with a knife, gave me a sense of vertigo, as it it were off-balance, tilted. The scene goes on much longer than necessary to make its point, with a female victim pushed face first through a piece of glass, then repeatedly stabbed to death (including a glimpse of her beating heart), and finally hanged, her body dropping through a horizontal stained glass window that showers debris on her roommate, impaling and killing her as well. The sequence elicited an awestruck whisper from my friend, who, knowing I had seen the film before, turned to ask, in all seriousness, “Is this the best horror film ever made?”

The famous first murder was stunning. It must be a trick of memory or perception, but the shot of the unfortunate victim, crouched and wounded as a hand shoots into frame with a knife, gave me a sense of vertigo, as it it were off-balance, tilted. The scene goes on much longer than necessary to make its point, with a female victim pushed face first through a piece of glass, then repeatedly stabbed to death (including a glimpse of her beating heart), and finally hanged, her body dropping through a horizontal stained glass window that showers debris on her roommate, impaling and killing her as well. The sequence elicited an awestruck whisper from my friend, who, knowing I had seen the film before, turned to ask, in all seriousness, “Is this the best horror film ever made?”

I gave a vague answer, to the effect that it contained several great set pieces. From my television viewing, I recalled that the pace was uneven, with long slow passages separating the key horror sequences. This became even more apparent on second viewing. Numerous tracking shots down long corridors (with little or no payoff) combine with dialogue of Suzy (Harper) and her friend Sarah (Stefania Casini) whispering about what may be lurking within the dance academy where the film is set, to create some uninspired longeurs. Clever camerawork adds some visual interest to these sequences, suggesting an omnipresent evil, a sort of magical alternative world of witchcraft at work even when nothing is overtly horrific happening.

In the end, however, it is not enough to sustain SUSPIRIA through its many slow scenes. The result is a film of highs and lows, worth seeing for its bravura style but falling short of the critical mass that would achieve masterpiece status. As the lights came up and we headed back to my car, my friend expressed some muted praise for the film as a whole but he was slightly disappointed since the opening reel had led him to believe he had discovered “the mother lode” of horror movies. Alas, that turned out to be not quite the case.

THE COMPLETE CUT

Since then, I have seen SUSPIRIA several more times: on home video and at least twice in theatres, including a 1990s American Cinematheque screening – part of an Argento retrospective, with Argento, actress Jessica Harper, and actor Udo Kier on hand to answer questions afterward (Argento graciously praised Harper’s contribution to the film, declaring that her smile before the final fade out “saved the movie”).* I had heard that a longer version existed, and if I eventually saw it on an imported Japanese laserdisc – once the best way to find complete versions of truncated movies. Unfortuantely, the image was pan-and-scan, if I recall; nevertheless, it was a godsend to see the film in complete form.

In the uncut version, the opening murder is even more brutal, including several more stab wounds and a clearer view of the victim’s still beating heart. The death by dog lingers even longer on the aftermath, watching as the canine rips long strands of raw flesh with its teeth. But most important, we finally learn why the blind man drew the ire of the witches in the first place.

There is a scene in which he arrives to work at the academy, leaving his dog outside. Moments later, a furious Miss Tanner (Alida Valli) burst into the dance instruction room, announcing that the dog has bitten someone, who had to be taken to the hospital. She fires the pianist, who is outraged at the accusation against his dog. Leaving, he announces that, although blind, he is not deaf, implying that he knows some dark secret about the academy. From this, we can conclude that the coven took action both to silence the man and to punish the dog that had attacked one of their own.

The other significant difference between the complete version and the U.S. cut is that the U.S. distributor (20th Century Fox, working through a subsidiary label) changed the opening title card. Instead of stark white letters on black background, the theatrical prints in America featured the word “Suspiria” spelled with pinkish “breathing” letters that looked a bit like mutant lungs. Although absurd (movie audiences typically laughed out loud at the sight of them), at the time I thought they had a certain charm. Now I’m glad to see the film, including titles, as Argento intended.

The other significant difference between the complete version and the U.S. cut is that the U.S. distributor (20th Century Fox, working through a subsidiary label) changed the opening title card. Instead of stark white letters on black background, the theatrical prints in America featured the word “Suspiria” spelled with pinkish “breathing” letters that looked a bit like mutant lungs. Although absurd (movie audiences typically laughed out loud at the sight of them), at the time I thought they had a certain charm. Now I’m glad to see the film, including titles, as Argento intended.

REAPPRAISAL

The restoration of SUSPIRIA to its uncut form heightened the already over-the-top impact and clarified a major plot point, yet over the years the film has somewhat dimmed for me. I still enjoy the aural-visual assault, but I find myself more quickly losing patience with the slower passages.

Also, after seeing the work of Mario Bava (Argento’s forefather in the field of Italian horror), SUSPIRIA no longer seems quite as innovative as it once did. In films like THE WHIP AND THE BODY and KILL, BABY, KILL, Bava had already explored the possibilities of artificial lighting schemes, using wild color palettes to create atmosphere and suggest the characters’ psychological states, regardless of the apparent light sources on screen. It would be fair to see that Argento took this approach at least two steps further with SUSPIRIA (and with its follow-up INFERNO).

Unfortunately, Argento borrowed something else from Bava: a predilection for spooky vignettes that lead nowhere. Bava’s WHIP AND THE BODY, in particular, feels like a half-hour story padded out with endless scenes of characters walking down dark corridors; the beauty of these scenes cannot conceal their dramatic paucity (which might be forgivable) but also their lack of a horrific payoff. Seldom do characters discover anything frightening at the end of those long corridors; the point of the scenes seems to be the journey, not the destination. In a similar manner, SUSPIRIA features numerous shots lingering over the dance academy’s architecture in an effort to create atmosphere and suggest that the house is a repository of evil.

There is also a Bavaesque moment when, after Suzy and Sarah listen to the footsteps of the academy’s staff descending into some unknown part of the building, the camera takes us on a brief trip through the corridors. It is a nice little moody sequence, but the payoff is almost literally nothing: the camera dollies into a darkened, empty room; then cuts to a zoom in on the moon, as a seque to the next scene (the death of the blind pianist). In retrospect, it becomes clear that the camera was following the path that the staff took to their lair; one might even conclude that the death in the following scene is actually a result of rites and incantations that the staff are performing in their lair. Nevertheless, we are still left with a pretty piece of film-making that lacks visceral impact and also fails to elicit a shudder of anticipation. Argento no doubt wants to tease us with the mystery of what is lurking behind the scenes, but as an evocation of Freud’s “Primal Scene,” this sequence falls far short of similar scenes in Roger Corman’s Poe films (an apparent influence on Argento), which frequently featured characters confronting locked doors that hid terrible secrets.

One element that helps push SUSPIRIA past its slow points is the soundtrack by Goblin (inexplicably renamed “The Goblins” in the film credits). This four-piece rock group (keyboards, guitar, bass, and drums) provided both entrancing musical motifs and almost avant garde aural assault. Most of the score is built around a repeating 14-note theme, played in 6/8 time, that suggests a demented fairy tale, effectively conveying the magical quality of the film. Many of the uneventful scenes are scored with whispering voices (titled “Sighs” on the soundtrack album); in a stero mix, the effect powerfully suggests unseen evil forces at work. The murder scenes are enhanced with jangly acoustic guitars; shrill, overlapping vocals; and pounding timpani drums. At times the music is discordant, almost atonal; it may not be a pleasant listening experience, but it adds the perfect punch to Argento’s visual excess – far more effectively than a conventional orchestral score could hope to do.

One element that helps push SUSPIRIA past its slow points is the soundtrack by Goblin (inexplicably renamed “The Goblins” in the film credits). This four-piece rock group (keyboards, guitar, bass, and drums) provided both entrancing musical motifs and almost avant garde aural assault. Most of the score is built around a repeating 14-note theme, played in 6/8 time, that suggests a demented fairy tale, effectively conveying the magical quality of the film. Many of the uneventful scenes are scored with whispering voices (titled “Sighs” on the soundtrack album); in a stero mix, the effect powerfully suggests unseen evil forces at work. The murder scenes are enhanced with jangly acoustic guitars; shrill, overlapping vocals; and pounding timpani drums. At times the music is discordant, almost atonal; it may not be a pleasant listening experience, but it adds the perfect punch to Argento’s visual excess – far more effectively than a conventional orchestral score could hope to do.

Though not known for providing in-depth characters, Argento cast his film well; his performers are, fortunately, interesting to watch, even if their roles are underwritten. Harper is the perfect picture of innocence; given little or no personality to work with, the actress uses her personal appeal to hold attention, so that we identify with her as we identify with the undefined heroes of fairy tales. Joan Bennett (known to fans of DARK SHADOWS) probably was not proud of appearing in a violent horror film (her last big screen appearance to boot), but she brings all her professionalism to the role of the academy’s head mistress, Madam Blanc. And Alida Valli (a popular character actress at the time) is perfect as Bennett’s right-hand woman; her stiff body language and sharp manner of speech (regardless of the dubbing) carve an entertaining characterization out of almost literally nothing.

The simplicity of characterization reflects the film’s fairy tale trappings. SUSPIRIA was conceived as a sort of violent, adult version of a story by the Brothers Grimm. Inspired by tales that co-screenwriter Daria Nicolodi’s grandmother had told her (of attending a school where the faculty practised magic at night), the screenplay was originally intended to feature young girls, until the producer objected that audiences would not tolerate seeing children put in mortal jeopardy. Argento had the last laugh: although the characters are played by women in their 20s, the dialogue retains its juvenile tone, and the academy’s doorknobs are set at eye-level, so that the dance students have to reach up for them as a child would for an ordinary door.

SEEN TODAY

SUSPIRIA remains Argento’s biggest international hit, a cult favorite that many fans consider to be his best work. Having seen all of Argento’s other horror films, I would have to disagree. SUSPIRIA is a remarkable exercise in style, but Argento’s most well-realized film, as a whole, is TENEBRE, followed closely by DEEP RED. Working in the giallo format, Argento seems more adept at sustaining a film from beginning to end; his murder-mystery plots may not stand up to logical scrutiny, but they do tie the set pieces together more firmly and keep the pace moving along at an exciting clip. The virtuoso stylization seems to be more under control, crafting both suspense and shocks, without weighting the expository scenes down.

SUSPIRIA’s cult reputation has generated a backlash over the years. Many viewers are put off by the artificiality of style. Some see the simple plot and characterization not not as dramatic devices in the service of creating a cinematic fairy tale but as simple artistic failings. Even Argento fans argue about the strengths and weaknesses. There is a consensus that the film starts strong and fades, never matching its outstanding opening; some even complain that the ending is a major disappointment.

Here, I have to offer a defense. Although I have always been as knocked out as anyone else by the famous first murder (especially the more explicit, uncut version), I find the ending equally satisfying, if not nearly as terrifying. The film finally kicks into gear; the plot, having lain dormant most of the running time, actually comes to life. Most of the movie suffers from a passive protagonist, who does little but take note of the strange events surrounding her; only at the end does Suzy take action.

In some ways, Suzy is a typical Argento character, an innocent artist whose benign view of the world is shattered by a glimpse of the dark side. An American, she has come to Germany to perfect her craft: like Argento’s other artists, she is trying to create beauty, which derives from fashioning order of of chaos, from imposing man-made discipline upon nature, creating artificial structures that delight the mind with their symmetry; however, her education ends up moving in the opposite direction, revealing forces of darkness and chaos that lurk beneath the surface of our perceived reality.

Unfortunately, what separates Suzy from previous Argento protagonists is that she is not galvanized into action at the beginning of the film. Films like THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (which is referenced at the end of SUSPIRIA) began with a murder, witnessed by a character who spent the rest of the plot trying to unravel the mystery; the only event Suzy witnesses is a hysterical student mumbling a few barely audible words before stumbling off into a thunderstorm. Suzy reports this to the headmistress but takes no other action. Although Alida Valli’s authoritative Miss Tanner compliments Suzy on her strong will, the young dancer spends much of the film in a lethargy that we eventually learn was induced by drugs inserted into her food.

In the third act, Suzy finally wakes up. After learning that the hysterical student – who was later murdered – was convinced that the faculty were witches, Suzy throws out her drugged food. (Apparently peeved, the forces of darkness send a black bat to nip at her hair, but she easily smashes it to death with a stool.) Now able to stay awake and count the footsteps as the faculty descend to their lair, Suzy traces them to Madame Blanc’s office, where in an archetypal Argento moment, the young student suddenly realizes the significance of what she saw and heard earlier; the fragments of memory unite, and she recalls that the murdered student was saying that turning a blue iris will reveal a hidden passage.

In the third act, Suzy finally wakes up. After learning that the hysterical student – who was later murdered – was convinced that the faculty were witches, Suzy throws out her drugged food. (Apparently peeved, the forces of darkness send a black bat to nip at her hair, but she easily smashes it to death with a stool.) Now able to stay awake and count the footsteps as the faculty descend to their lair, Suzy traces them to Madame Blanc’s office, where in an archetypal Argento moment, the young student suddenly realizes the significance of what she saw and heard earlier; the fragments of memory unite, and she recalls that the murdered student was saying that turning a blue iris will reveal a hidden passage.

Following the directions, Suzy, in a sense, goes down the rabbit hole, discovering the source of evil at play throughout the film. She sees Madame Blanc leading the rest of the faculty in a ceremony that suggests a blasphemous inversion of a church service, and finds herself confronting Helana Markos – a witch who survived a fire that supposedly killed her years ago. Speaking in a raspy (and frankly overdone) voice that suggests a cartoon version of THE EXORCIST, her face covered in ghastly burn marks, Helena is the “Black Queen,” who sits at the head of the coven operating in the academy.

This confrontation between ancient evil and youthful innocence is a splendid climax. The imbalance in powers between the two characters suggests a hopeless mis-match: not only can Helena render herself invisible; she can also summon the living dead (Sara, drooling blood, pins and needles poking out of her flesh and eyes). All Suzy has going for her is desperation and a make-shift weapon, the sharply pointed “feather” from the statue of a bird. (The statue suspiciously resembles the titular “Bird with the Crystal Plumage,” which figured prominently in solving the mystery of Argento’s directorial debut. The statue appears at approximately the same point, structurally, as the living bird did in the previous film.)

This confrontation between ancient evil and youthful innocence is a splendid climax. The imbalance in powers between the two characters suggests a hopeless mis-match: not only can Helena render herself invisible; she can also summon the living dead (Sara, drooling blood, pins and needles poking out of her flesh and eyes). All Suzy has going for her is desperation and a make-shift weapon, the sharply pointed “feather” from the statue of a bird. (The statue suspiciously resembles the titular “Bird with the Crystal Plumage,” which figured prominently in solving the mystery of Argento’s directorial debut. The statue appears at approximately the same point, structurally, as the living bird did in the previous film.)

Fortunately, it is enough. Guided by good fortune – or just plain luck – plus a glimpse of the witch’s outline, Suzy is able to drive her point home, precipitating the destruction of the coven and the academy in a spectacular display of exploding objects, overturned furniture, ripping wall paper, and – at last – a cleansing fire, leaving no doubt that the vile contagion infecting the academy has been thoroughly eradicated. Suzy’s smile of relief, as she wanders from the immolating structure, is shared by the audience. As in a fairy tale like “The Three Little Pigs,” we identify with and exalt for the survival of our hero. The other characters are not believable people whose deaths we mourn; they are shadows, fragments, bits and pieces of our psyche personified on screen and wiped away so that our better self can emerge, unhampered, in the form of the character who will defeat the evil.

Fortunately, it is enough. Guided by good fortune – or just plain luck – plus a glimpse of the witch’s outline, Suzy is able to drive her point home, precipitating the destruction of the coven and the academy in a spectacular display of exploding objects, overturned furniture, ripping wall paper, and – at last – a cleansing fire, leaving no doubt that the vile contagion infecting the academy has been thoroughly eradicated. Suzy’s smile of relief, as she wanders from the immolating structure, is shared by the audience. As in a fairy tale like “The Three Little Pigs,” we identify with and exalt for the survival of our hero. The other characters are not believable people whose deaths we mourn; they are shadows, fragments, bits and pieces of our psyche personified on screen and wiped away so that our better self can emerge, unhampered, in the form of the character who will defeat the evil.

With its bloody violence, SUSPIRIA may not fully suppor this reading. In fact, the very nature of film, with actors playing characters, tends to subvert the nature of fairy tales, which exist more fully in the realm of the imagination, making it easier to interpret, for example, the first two little pigs as not separate entities but las ess mature versions of the third pig – that is, as stages of psychological development that will lead to the maturity necessary to survive. (See Bruno Bettelheim’s The Use of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales.)

SUSPIRIA may not resonate with the full force of a tale by the Brothers Grimm, but as an exercise in excessive style it is one of the most amazing experiences ever recorded on celluloid. A strange combination of the art house and the slaughterhouse, it may be too violent for the typical cineaste and too contrived for the typical gore-hound. Yet somehow Argento impressively straddles both worlds, offering a unique vision of magic and the supernatural that deserves its place in horror movie history.

TRIVIA

INFERNO, the 1980 sequel to SUSPIRIA, makes it clear that the trilogy (which was finally completed with MOTHER OF TEARS) is inspired by “Levana and Our Ladies of Sorrow,” an essay in Thomas De Quincey’s non-fiction book, Suspiria de Profundis, which is a sequel to his earlier Confession of an English Opium-Eater. In “Levana,” De Quincey recounts an opium-induced vision of three supernatural figures (Mater Lachrymarum, Mater Suspiriorum, and Mater Tenebrarum), who oversea the tears of sadness, the sighs of resignation, and the darkness of despair that afflict mankind. Helena Markos, the witch ensconced in the German dance academy, is actually Mater Suspiriorum (the Mother of Sighs), although she is never so designated in SUSPIRIA itself (where we are told she was called “The Black Queen”). In fact, about the only obvious reference in SUSPIRIA to De Quincey’s essay is the title.

DVD DETAILS

SUSPIRIA is currently available as a 2-Disc Special Edition DVD (see below), but the preferred version is Anchor Bay’s limited edition 3-Disc box set from 2001. Now out of print (some copies are still available from specialty dealers), this set contains the uncut 98-minute version of the film on Disc 1, plus theatrical trailers, TV and radio spots, a gallery of posters and stills, a music video (of former Golbin-member Claudio Simonetti’s new band, Daemonia, performing a beefed-up version of the “Suspiria” main title), and talent bios. The soundtrack features three language options: English, Italian, and French. Unfortunately, there are no subtitles, so English viewers are stuck with the English soundtrack (not a bad choice, considering that is the language of the lead actress, but it would be nice to hear the Italian dialogue for a change and know what was being said). The American trailer features a campy nursery rhyme, a phony skull, and the “breathing” letters seen in the U.S. version of the film. The Italian trailer is virtually abstract: a series of still images giving no hint of the plot, while credits emphasize Argento’s name, as if his reputation alone is enough to sell the film.

SUSPIRIA is currently available as a 2-Disc Special Edition DVD (see below), but the preferred version is Anchor Bay’s limited edition 3-Disc box set from 2001. Now out of print (some copies are still available from specialty dealers), this set contains the uncut 98-minute version of the film on Disc 1, plus theatrical trailers, TV and radio spots, a gallery of posters and stills, a music video (of former Golbin-member Claudio Simonetti’s new band, Daemonia, performing a beefed-up version of the “Suspiria” main title), and talent bios. The soundtrack features three language options: English, Italian, and French. Unfortunately, there are no subtitles, so English viewers are stuck with the English soundtrack (not a bad choice, considering that is the language of the lead actress, but it would be nice to hear the Italian dialogue for a change and know what was being said). The American trailer features a campy nursery rhyme, a phony skull, and the “breathing” letters seen in the U.S. version of the film. The Italian trailer is virtually abstract: a series of still images giving no hint of the plot, while credits emphasize Argento’s name, as if his reputation alone is enough to sell the film.

Disc 2 contanis a 52-minute Suspiria 25th Anniversary documentary, featuring interviews with Argento, co-writer Daria Nicolodi, cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, members of Goblin (Augostino Morangalo, Massimo Morante, Fabio Pignatelli, Claudio Simonetti), Jessica Harper, Stefania Casini, and Udo Kier. This gives some pretty good insight into the inspiration for and making of the film. Hardcore fans may wish for even more in-depth detail, but what is here is well put together and even interesting enough to appeal to non-fans. Kier (who has only one brief scene in the film, as a skeptical psychiatrist) signs off by expressing a wish that he and Argento work together again – which came true six years later with MOTHER OF TEARS.

The final disc is a soundtrack CD containing three bonus tracks not found on the original vinyl release from 1977. The bonus tracks are somewhat misleadingly titled “Suspiria (Celeste and Bells),” “Suspiria (Narrator),” and “Suspiria (Intro),” implying that they are all remixes or outtakes of the main title theme. This turns out not to be the case:

- “Suspiria (Narrator)” contains no narration; it is actually an alternate take of the track titled “Markos,” which features heavy pounding on the drums and some ripping baselines playing over a sequenced synthesizer riff.

- “Suspiria (Celeste and Bells)” is the track that actually features narration. Keyboardist Claudio Simonetti chants non-grammatical nonsense about witches, while celesta and bells perform a subtle version of the main theme.

- “Suspiria (Intro)” is not an intro but a new recording of main title music. Although there is no separate credit on the CD, which is attributed solely to Goblin, this version is clearly the one performed by Daemonia, as seen in the music video on Disc.

The DVD set also contains a miniature cardboard poster listing the Chapter Selections on the back, a set of nine stills printed on 7×5 matte paper; and a colorful 28-page booklet. Packed with images (including a reproduction of the original U.S. theatrical poster), the latter features an introduction by Scott Michael Bosco, an appreciation of Argento’s work by Travis Crawford, and a lengthy interview with Jessica Harper (who turned down a small role in ANNIE HALL to play the lead in SUSPIRIA).

SUSPIRIA (1977). Directed by Dario Argento. Written by Dario Argento and Daria Nicolodi. Cast: Jessica Harper, Stefania Casini, Flavio Bucci, Miguel Bose, Barbara Magnolfi, Susanna Javiocoli, Eva Axen, Joan Bennett, Alida Valli, Jacopo Mariani, Udo Keir.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Book Review: Suspiria de Profundis

- Film & DVD Review: Inferno

- Film Review: Mother of Tears

*The American Cinematheque screening of SUSPIRIA offered evidence that the film has a cult reputation that extends beyond that of Argento’s other work. The weekend retrospective of Argento’s work was well attended, but the SUSPIRIA screening sold out so fast that an unscheduled midnight screening was added on the day of the event, and that sold out, too. The only other sell out was for FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET – a film difficult if not impossible to see in the U.S., not available on VHS or laserdisc at that time. (PULP FICTION fans take note: Quentin Tarantino showed up too late to purchase a ticket.)

Mother of Tears (2007) – Film Review

Mater Lachrymarum, Our Mother of Tears. She it is that night and day raves and moans, calling for vanished faces. She stood in Rama, when a voice was heard of lamentation – Rachel weeping for her children, and refusing to be comforted. She it was that stood in Bethlehem on the night when Herod’s sword swept the nurseries of Innocents […] Her eyes are sweet and subtle, wild and sleepy by turns, oftentimes rising to the clouds; oftentimes challenging the heavens.

– Thomas De Quincey, Suspiria de Profundis

I, Varelli, an architect living in London, met the Three Mothers and designed and built for them three dwelling places. One in Rome, one in New York, and the third in Freiburg, Germany. I failed to discover until too late that from those three locations the Three Mothers rule the world with sorrow, tears, and darkness. Mater Suspirorum, the Mother of Sighs and the oldest of the three, lives at Freiburg. Mater Lachrymarum, the Mother of Tears and the most beautiful of the sisters, holds rule in Rome. Mater Tenebrarum, the Mother of Darkness, who is the youngest and cruelest of the three, controls New York.

– From “The Three Mothers” in INFERNO