When it comes to putting dinosaurs on the screen, Universal is certainly the studio that knows how, and in LAND OF THE LOST the dinos do not disappoint, thanks to the wonderful creature design work of Crash McCreery (who worked on all three JURASSIC PARK movies) and effects supervisor Bill Westenhofer (THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE). They were all ably assisted by a very large effects crew, including over 30 key animators who toiled away under Rhythm and Hues animation supervisor, Matt Shumway.

When it comes to putting dinosaurs on the screen, Universal is certainly the studio that knows how, and in LAND OF THE LOST the dinos do not disappoint, thanks to the wonderful creature design work of Crash McCreery (who worked on all three JURASSIC PARK movies) and effects supervisor Bill Westenhofer (THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE). They were all ably assisted by a very large effects crew, including over 30 key animators who toiled away under Rhythm and Hues animation supervisor, Matt Shumway.

Which makes thinking about all the animation Ray Harryhausen accomplished in each of his movies, entirely on his own, truly astounding!

Unfortunately, the comic premise which delivers Will Ferrell and his two cohorts into this “Land of the Lost” is mostly of a standard issue variety, making the film susceptible to the same charges that always plagued Harryhausen’s films: “The animated creatures are great, but the acting and script are nothing to get excited about.”

Actually, the first half of the movie works quite well, and is not nearly as bad as it might have been, since as soon as Ferrell lands in the alternate universe we are treated to an fearsome T-Rex, whose immediately pursues the explorers across a great chasm into a conveniently located cave.

From there, we get a truly surreal series of landscapes provided by production designer Bo Welch (a favorite designer for both Tim Burton and Mike Nichols), almost as if the trio of adventurers had stepped into a live-action version of Bob Clamplett’s delightfully subversive 1938 WB cartoon, PORKY IN WACKYLAND.

Helping enormously in these scenes is the location work done for at Dumont Dunes and Trona Pinnacles, in the California Desert National Conservation Area, near Death Valley that mixes quite nicely with the huge studios sets built on the stages at Universal. However, what works in a 7- minute cartoon is much harder to sustain over the course of a 100-minute movie, and as a result, the second half of the movie suffers accordingly, since it soon becomes clear the filmmakers are willing to allow anything to occur for the sake of a gag, even if it’s a gag that doesn’t really work. Such laxity tends to makes the laughs become less infrequent as the film proceeds from one disjointed episode to the next, until Will Ferrell’s final encounter with the T-Rex (named Grumpy), becomes so totally absurd it actually makes things less funny than if they they had just played it straight.

Presumably, this kind of “anything goes” comedy would have worked if there were actors like The Marx Brothers on board for the ride, but needless to say, Will Ferrell and his partners are simply not comedians on that rarified level, so are unable to elevate such slight situations and material beyond the routine.

However for all Dino fans, there are several impressive CGI scenes involving a a whole rookery of Pterasour eggs that are about to hatch, a heard of small Compsognathuses, some Velociraptors hungry for either ice cream or the ice cream vendor, and perhaps best of all, a male and female T-Rex team, one of which is colored red so it can easily be distinguished from it’s mate, who meets an explosive end.

[serialposts]

Tag: time travel

Terminator 2: Judgment Day – Blu-ray Review

If we had to pick the five greatest theatrical experiences of our adult life (eliminating childhood, where even the lights going down could give goosebumps) then catching TERMINATOR 2: JUDGMENT DAY on opening day back in July of 1991 would rank highly among them. It’s an amazing thing to walk out of a theater with your head buzzing after witnessing something utterly, totally, and demonstrability different, and TERMINATOR 2 was exactly that – an action epic with an unlikely emotionality at its core, a special effects extravaganza that utilized brand-new technology and combined it flawlessly with reliable, older methods, and, perhaps most amazingly, a sequel that outdid the original in every imaginable way.

The success of The Terminator in 1984 served as a calling card for the talents of both star Arnold Schwarzenegger and writer-director James Cameron, with both having labored for years in low-budget genre efforts before joining forces on a vehicle that called on each of their strengths; playing a (nearly) emotionless cyborg negated the stars thespian weaknesses; the director’s skills, honed working on the special effects for numerous ultra low-budget productions (including numerous Roger Corman efforts and some nifty matte paintings for Escape from New York), allowed Cameron to create viable future tech for very little money. The film was a smash, and the fortunes of both men rose at a geometric rate for the remainder of the decade, creating almost ridiculously high expectations for the inevitable sequel.

Following months of pre-release hype surrounding both the return of Arnold Schwarzenegger to his most iconic role and the use of the groundbreaking digital morphing effects, TERMINATOR 2 did finally debut to virtually universal critical and audience acclaim. Though its action set pieces are justifiably famous, it is the deliberate pacing of James Cameron’s editing that has you gripping for the figurative edge of your seat long before the bullets start flying. Even the major action beats utilized longer takes and far less cutting than you’d find in a similar blockbuster. Cameron always keeps the special relations of both people and objects easy to follow; unlike headache-inducing shows like Transformers, the editing rhythms carry through and establish momentum throughout the film’s running time (watching Michael Bay’s film is like being in the car with a 16-year-old learning to drive a stick shift), and you always know where everyone and everything is in relation to everything else – a depressingly lost art. And though digital effects (in their infancy in 1991) are utilized whenever Robert Patrick’s T-1000’s shifted its liquid metal shape, the rest is achieved through expert models and gasp-inducing stunt work.

Just as important to TERMINATOR 2’s success are the principal actors, almost all of whom make something quite special out of their roles – whether, in the case of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Linda Hamilton, they were returning to roles they had previously created, or newer editions to the cast. Under James Cameron’s careful direction, Schwarzenegger has always seemed livelier and more comfortable, able to take gentle pokes at his image without degenerating into outright mockery. His reading of certain lines – like his response to Edward Furlong’s shocked exclamation that he was prepared to kill a man in broad daylight (“Of course, I’m a Terminator”) is priceless, and his performance is peppered with unexpected character moments.

Linda Hamilton’s Sarah Connor is simply amazing to behold, incredibly fit and muscular without being freakishly so. She was one of the more unusually attractive actresses of that era, and Cameron photographs her with a mixture of love and awe – similar to the way Michael Bay photographs an aircraft carrier. The authority that she carries holds the film’s more questionable plot turns in check and more than makes up for TERMINATOR 2’s only real shortcoming, the irritating, lispy performance of Edward Furlong as John Connor – the future leader of the Resistance that we wouldn’t follow across a room.

After the bankruptcy of Carloco Pictures many moons ago, the home video rights to TERMINATOR 2 have leapt from one company to another – and from VHS to Laserdisc to DVD and now Blu-Ray – with decidedly mixed results. After one of the earliest “must have” special edition releases on Laserdisc, all subsequent releases have built off this foundation – including commentary tracks featuring nearly all the production personnel, an extended (and superior) 153min cut of the film (the theatrical ran 137min) that reinstated Michael Biehn’s appearance as Kyle Reese, and literally hundreds of documents and photos from the production. The DVD releases saw the debut of an “extended special edition” running just a few minutes longer than the special edition, and including only two additional scenes – the T-1000 using his fingertips to scan John’s bedroom, and a coda taking place in a futuristic Washington D.C., with Sarah as a grandmother watching as her son, Senator John Connor, play with his daughter in an idyllic park, the Skynet threat finally defeated.

Lionsgate’s new Blu-Ray represents a noticeable improvement over their previous Blu-Ray, taking advantage of the soon-to-flop Terminator: Salvation to re-master TERMINATOR 2. While only those intent on heavily scrutinizing the image on large displays will notice most of the image upgrade, the drastic improvement that the lossless audio offers is immediately evident (back in the Laserdisc days, that first metallic crunch of the Terminator foot crushing the skull always knocked us out of the chair, and we were glad to have that feeling once again).

There has been a lot of grumbling in regards to the use – or misuse – of digital noise reduction on the title, and we wish that we could offer a more definitive answer. TERMINATOR 2 was never a particularly naturalistic-looking film; virtually the entire show is shot with heavy blue filtering, giving even human features near-metallic sheen. We suspect that some people may be mistaking this (and it is the way that the film was originally shot) for a DNR byproduct, though I’ll leave it to people with displays 65-inches and over to determine. The transfer looked good to us.

The extras represent a best-of compilation of previously offered items, with both the original commentary plus the slightly newer commentary track featuring James Cameron and co-writer William Wisher that had been offered with the “Extreme Edition” DVD release – it’s more interesting than the somewhat jumbled cast-crew track by virtue of concentrating on Cameron’s point of view (it is also scene-specific whereas the other is not.)

All extant versions are here as well, though you still have to put in the code 82997 to access the Extended Version; the two scenes that make up the difference between the Extended and Special editions are available separately on the disc and both represent solid cuts (the fingertip scan looks sillier than it probably read and mucks with the pacing, while the D.C. coda is embarrassingly stiff.)

Much of the previous BTS content had been carved up for picture-in-picture content that can be set to run with the film. All the theatrical teasers and trailers are also present (in HD) including the terrific “I promise, I will not kill anyone” spot. If you haven’t already bought the previous edition, this represents a pretty good value for money – particularly for the terrific lossless audio track. If you’re worried about heavy use of DNR, you can check out a very comprehensive screenshot comparison at DVD Beaver. Recommended.

[serialposts]

Sound of Thunder (2005) – Retrospective Science Fiction Film Review

A SOUND OF THUNDER, a science fiction film based on the Ray Bradbury short story of the same name, is a colassal disapopintment – unworthy of the memorable source material. It seems as if the film wants to be an old-fashioned B-movie, but it is nowhere near that good; even worse, the idea is one that requires an A-Movie budget in order to work at all. Consequently, instead of a neat little movie told with modest production values, the film looks cheap and unconvincing, thanks to the terribly cartoony computer-generated imagery – not only for the dinosaurs but also for the futuristic cityscapes (which, with their awkward staging and camera angles, suggest that the actors were working on blank sets, onto which the digital backgrounds were added later – an effect done much better in SIN CITY). Weirdly, the design team includes Syd Mead (BLADE RUNNER) and Ray “Crash” McCreery (JURASSIC PARK), but you would never guess it from the on-screen results.

A SOUND OF THUNDER, a science fiction film based on the Ray Bradbury short story of the same name, is a colassal disapopintment – unworthy of the memorable source material. It seems as if the film wants to be an old-fashioned B-movie, but it is nowhere near that good; even worse, the idea is one that requires an A-Movie budget in order to work at all. Consequently, instead of a neat little movie told with modest production values, the film looks cheap and unconvincing, thanks to the terribly cartoony computer-generated imagery – not only for the dinosaurs but also for the futuristic cityscapes (which, with their awkward staging and camera angles, suggest that the actors were working on blank sets, onto which the digital backgrounds were added later – an effect done much better in SIN CITY). Weirdly, the design team includes Syd Mead (BLADE RUNNER) and Ray “Crash” McCreery (JURASSIC PARK), but you would never guess it from the on-screen results.

Briefly, the story involves time travel for profit: rich people pay big bucks to go back in time and shoot an allosaurus. Unfortunately, something goes wrong on one trip, and “time ripples” from the event begin changing course of evolution on a daily basis, forcing our characters to go back to fix what went wrong.

It’s not a bad idea for an action movie, but it falls prey to all the usual time travel paradox problems. The most obvious is that the hunt always goes back to kill the same dinosaur over and over, without ever meeting any of the previous hunting parties. Yet, when trying to “fix” the problem, our hero goes back in time and does see the hunting party that made the mistake, issuing a warning to one and preventing the catastrophe from happening. Whether or not time travel can ever make sense, the story should at least be internally consistent, and this clearly is not.

This kind of nitpick stuff might be forgivable if the film flowed along at an exciting pace, but it just lays there. It sort of almost works on an “I wonder what will happen next” level, but the action is tepid, the charactes thin, and the cast just doesn’t have the charisma or the talent to sew a silk purse out of a sow’s ear (exception being Ben Kingsley, who actually is the one bright spot here, as the greedy businessman who owns the time travel company).

Director Peter Hyams (who also photographed) used to be a decent filmmaker back in the 1970s, when he often wrote his own scripts. He was never great, but at least he was trying to make films with some personality and competence. Now, he seems to be nothing but a professional hack, churning out soulless movies just to make a living. But at least his John-Claude Van Damme movies (SUDDEN DEATH and TIME COP) had a tiny bit of pizzazz to them; even THE RELIC was a more interesting monster movie than SOUND OF THUNDER.

It’s too bad. The Ray Bradbury story is very good. Expanding its simple concept into a feature no doubt presented difficulties, but it deserved better treatment that it got. The batting average of Bradbury story-to-film adaptations is very low, and SOUND OF THUNDER only makes it worse.

A SOUND OF THUNDER (2005). Directed by Peter Hyams. Screenplay by Thomas Dean Donnelly & Joshua Oppenheimer and Gregory Pointer; screenstory by Donnelly & Oppenheimer, based on the short story by Ray Bradbury. Cast: Edward Burns, Catherine McCormack, Ben Kingsley, Wilfred Hochholdinger, David Oyelowo, Jemima Rooper.

Timecrimes (2007) – Science Fiction Film Review

Sitting around in the yard of your isolated country home, taking in the air on a quiet day, you would think that a little voyeurism could hardly get you into a world of trouble – even if you are a married, middle-aged man. Strapping on a pair of binoculars and watching a beautiful young woman take off her t-shirt cannot have any life-threatening repercussions. Even if you are curious (or foolish) enough to wonder why she is doing this, sneaking off and taking a closer look cannot lead to danger. Certainly, no harm can befall you under such simple circumstances. Au contraire, warns writer-director Nacho Vigalondo in his science fiction film, TIMECRIMES. Voyeurism can have lethal consequences when combined with a time machine, as you travel back to the past and try to undo what has been done, sending yourself on a labyrinthine journey with potentially catastrophic consequences for your own existence and possibly the world.

Sitting around in the yard of your isolated country home, taking in the air on a quiet day, you would think that a little voyeurism could hardly get you into a world of trouble – even if you are a married, middle-aged man. Strapping on a pair of binoculars and watching a beautiful young woman take off her t-shirt cannot have any life-threatening repercussions. Even if you are curious (or foolish) enough to wonder why she is doing this, sneaking off and taking a closer look cannot lead to danger. Certainly, no harm can befall you under such simple circumstances. Au contraire, warns writer-director Nacho Vigalondo in his science fiction film, TIMECRIMES. Voyeurism can have lethal consequences when combined with a time machine, as you travel back to the past and try to undo what has been done, sending yourself on a labyrinthine journey with potentially catastrophic consequences for your own existence and possibly the world.

This Spanish-language time-travel thriller earned critical kudos when released to art houses last year, and it is not hard to see why. As a director, Nacho Vigalondo sweeps you up into his tale and keeps you running at what seems like full speed toward the finish line; as a writer, he lays out the expostion with admirable clarity, even as events loop back on themselves, creating possible confusion.

TIMECRIMES begins innocuously enough, lulling the viewer into a false sense of safety before introducing the mystery-thriller elements. When Hector (Karra Elejalde) investigates in the woods, he finds the young woman apparently dead, and he finds himself pursued by a mysterious man with a bandaged face – presumably the woman’s murderer. This leads to a tense cat-and-mouse chase that sends Hector to a nearby facility seeking shelter, and then the film gets down to telling us what is is really about.

The facility is some kind of experimental lab. The place is empty on a weekend, but the only attendant (director Nacho Vigalondo himself) (whose nervous manner should clue us in that something is up) has turned on a time machine. Hector uses it to go back and prevent the girl’s death, and we learn why the attendant was acting so strangely: he knew Hector was going to arrive at the facility, because Hector had popped out of the time machine a few minutes after it was turned on, explaining why he was there to the attendant, who then had to go through the motions of acting surprised when Hector showed up on foot.

If that sounds like a time-twister that will have your brain in knots, the rest of TIMECRIMES works in a similar way. Hector’s effort to change the past runs into interference from a mysterious source, forcing him to go back to an even earlier point in time. The result is three Hectors running around in the same time frame; the problem is that, in attempting to change the past, he must not doing anything to prevent his previous selves from stepping into the time machine. As the attendant explains, all the pieces must fit, or Hector could cease to exist, with who knows what consequences for the time-space continuum. Consequently, Hector finds himself deliberately re-staging action that he had witnessed prevously from a different point of view, such as forcing the woman to take off her shirt, so that his first self, sitting in a lawn chair and watching through his binoculars, will see her and take the fateful steps that will lead him eventually into the time machine.

You won’t need an advanced degree in the Theory of Relativity to see where the twists and turns in the screenplay are headed: straight into a paradox that goes totally unackowledged when the masked man’s identity is revealed. Rather like THE TERMINATOR, TIMECRIMES creates a scenario with a fairly gaping plot hole, in which effect precedes cause, and the only way to rationalize away the problem is to fault human perception of time and imagine that events exist in a fixed, fated loop.

Unfortunately, TIME compounds the crime by suggesting that the laws of cause-and-effect are, indeed, in effect. Although it is hard to be sure in the rush of events, actions seem slightly different each time Hector experiences them, suggesting that his intervention is changing things; he just needs to maintain the illusion of continuity so that the overall flow will remain the same.

This leads to a morally reprehensible ending in which Hector makes a life-and-death decision, saving one character at the expense of another. Nacho Vigalondo apparently wants us to sympathize with Hector’s dilemma; after all, he didn’t asked to be swept up into this time-travel paradox. The problem is: it’s not totally clear that Hector’s hand is forced by events beyond his control. So much of what he has done in his time-tripping is maintaining an illusion – that is, staging some action so that it will appear to his former self the way he remembers seeing it. What actually happens is another matter, and it is not to impossible to imagine some way of avoiding the dilemma altogether.

To be fair, Hector is a bit pressed for time, so perhaps he we cannot blame him too much for not figuring out some alternative. But the calm way he returns to his former life – forced calm, but calm nonetheless – is quite an affront to the audience when we know he has blood on his hands.

On the other hand, perhaps this vexing conclusion is what gives TIMECRIMES its jolt – makes it more than just an exerciese in playing with time travel paradoxes. The pieces all fit, bringing the story to a satisfying end on a narrative level but leaving the audience with some unpleasant thoughts to consider after the lights have gone back up. An American remake is already in the works; it will be interesting to see if the obligatory happy ending (that will no doubt be added) will resolve the issue or simply feel like a cop out.

This clever film may ultimately be a little too clever for its own good; however, it remains an engrossing adventure that uses time travel to craft an exciting thriller with enough intensity and scares to rival a good horror film. Elejalde is great as Hector: not a leading man type, he is a completely convincing as an ordinary man caught up in a situation almost beyond his understanding. Special effects are virtually non-existant, but this is one science fiction film that does not need them; even the scary appearance of the mysterious figure is simply some bloody bandages wrapped around a face. Whatever its flaws, TIMECRIMES is an excellent example of what can be achieved with good craftsmanship and a lot of imagination.

If you missed TIME CRIMES during its brief theatrical run in 2008, you should catch it on home video. The DVD, which came out this week, includes featurettes, short films, and deleted scenes.

TIME CRIMES (Los Cronocrimenes, 2007 – released 2008). Written and directed by Nacho Vigalondo. Cast: Karra Elejalda (Hector), Candela Fernandez (Clara), Barbar Goenaga (The Girl in the Forest), Nacho Vigalondo (the Young Scientist).

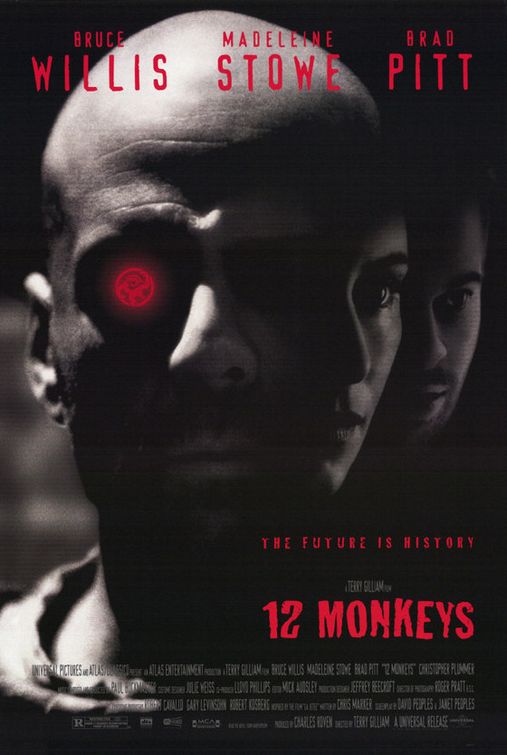

12 Monkeys (1995) – Science Fiction Film Review

An Ambitious and amazing feature-length re-imagining of the classic short subject “La Jetee.”

An Ambitious and amazing feature-length re-imagining of the classic short subject “La Jetee.”

This is feature-length remake of LA JETEE, the short-subject masterpiece by Chris Marker that portrayed time travel as a kind of moebius strips folding back on itself. The original short was a remarkable piece of film-making with a style inextricably linked to its content. Perhaps LA JETEE’s auteur, Chris Marker, was simply using techniques from his documentary background (the story is told in a series of still frames, with a voice-over narrating the events); however, those frozen moments of time cannot help but enhance a story about the nature of time and returning to specific moments over and over again.

In retrospect, there was never any chance that 12 MONKEYS would turn out to be a literal remake; instead, it is a re-imagining of the basic premise, dramatized in conventional dramatic terms. Needless to say, director Terry Gilliam films his actors at twenty-four frames per second, not in still photographs. Nevertheless, 12 MONKEYS is not simply a Hollywood mainstreaming of a European art film. In fact, this independently financed effort was probably the most difficult and challenging film released by a major studio (Universal Pictures) in 1995. Continue reading “12 Monkeys (1995) – Science Fiction Film Review”