An atmospheric and well-executed genre piece from Nobou Nakagawa, Japan’s equivalent to Terence Fisher.

If Japanese director Nobou Nakagawa is known at all in the U.S., it is because of Jigoku (1960), an art-house perennial and the recipient of a Criterion Collection release on DVD and streaming services. This might lead western audiences to view Nakagawa as a highbrow artiste, but in truth the director had a successful career in the 1950s and 1960s as a director of modestly budgeted horror films, appealing to general audiences by presenting familiar genre tropes with a sense of impeccable craftsmanship. The closest American equivalent from the era would be Roger Corman, but England’s Terence Fisher and Italy’s Mario Bava also come to mind: all three took material that could have been conventional in other hands and turned it into something remarkable.

If Japanese director Nobou Nakagawa is known at all in the U.S., it is because of Jigoku (1960), an art-house perennial and the recipient of a Criterion Collection release on DVD and streaming services. This might lead western audiences to view Nakagawa as a highbrow artiste, but in truth the director had a successful career in the 1950s and 1960s as a director of modestly budgeted horror films, appealing to general audiences by presenting familiar genre tropes with a sense of impeccable craftsmanship. The closest American equivalent from the era would be Roger Corman, but England’s Terence Fisher and Italy’s Mario Bava also come to mind: all three took material that could have been conventional in other hands and turned it into something remarkable.

A perfect example of this is Nakagawa’s atmospheric and intriguing entry in the Japanese Bakeneko or “Ghost Cat” genre, Borei Kaibyo Yashiki, known in the U.S. as Black Cat Mansion, though the title is sometimes translated as Mansion of the Ghost Cat (perhaps because, although a black cat is seen beneath the credits, the ghost cat itself is definitely not black). The story follows a Japanese couple who, for the benefit of the wife’s health, move from the city to the countryside, where they take up residence in an old mansion, which doubles as their home and as a clinic. Unfortunately, the mansion turns out to be haunted by a malevolent spirit, which seems to be targeting the wife.

Inquiries reveal that, hundreds of years ago, the mansion was the scene of a ghastly crime, when a brutal lord murdered a samurai and raped the samurai’s blind mother, who committed hara-kiri after charging her pet cat with seeking revenge (“Lap my blood, and imbibe my hatred!”). After the mother’s death, the cat transformed into a humanoid spirit, killing off all members of the household, including the servants. Back in the present day, we learn that the tormented wife is a descendant of one of those servants – in effect, an innocent victim of a vengeful “grudge” that is not very discriminate about its victims.

The narrative of Black Cat Mansion is wrapped in three layers, including two levels of flashback. We start in the present, with Dr. Kuzumi (Toshio Hosokawa) roving through the corridors of a city hospital late at night while a black cat meows outside, reminding him of the time he and his wife (Yuriko Ejima) moved to the haunted mansion. This takes us to the events concerning him and his wife, which in turn leads to the extended flashback regarding the history of the mansion. The movie then returns step by step to the present, first to the story of Kuzumi and his wife at the mansion, then to Kuzumi at the hospital.

The narrative of Black Cat Mansion is wrapped in three layers, including two levels of flashback. We start in the present, with Dr. Kuzumi (Toshio Hosokawa) roving through the corridors of a city hospital late at night while a black cat meows outside, reminding him of the time he and his wife (Yuriko Ejima) moved to the haunted mansion. This takes us to the events concerning him and his wife, which in turn leads to the extended flashback regarding the history of the mansion. The movie then returns step by step to the present, first to the story of Kuzumi and his wife at the mansion, then to Kuzumi at the hospital.

The symmetrical structure neatly organizes a story that might otherwise have seemed stitched together to achieve feature length (though only barely, at 69 minutes). We get a sense of going deeper and deeper into the past, like peeling back a proverbial onion to reveal an elusive mystery. The back-the-the-present structure also provides a sense of finality to climax that is a bit vague in its details (we know what happened, though why is not precisely clear – at least not to Western viewers relying on subtitles).

Nakagawa presents the material with several stylistic flourishes that transform the genre material into a distinctive form of popular art. The wraparound segment begins with the camera drifting past an unexplained scene of a body being wheeled through a darkened hospital hallway like a ghostly funeral procession – which Dr. Kuzumi’s voice-over totally ignores, as if his thoughts are too preoccupied to bother noting the weird visual flashing before our eyes. Totally unrelated to the narrative, the scene serves only as visual warning sign, an omen of the supernatural horrors to come.

When Kuzumi and his wife arrive at the mansion, the scenery is straight out of the horror movie playbook, right down to the ominous raven perched atop a branch of one of the many wild plants apparently reclaiming the land from the disused property. Nakagawa films the scene in a simple, elegant long shot, slowly tracking to follow as the front gate is opened and the characters enter; the effect is to make the audience feel as if they, too, are crossing a borderland into a different world, a slightly dreamy landscape where anything can happen. The effect is punctuated when the extended take is broken by a single insert closeup, as the wife sees a mysterious woman within a side building – only to find that the ghostly figure is gone when Kuzumi comes to see.

When Kuzumi and his wife arrive at the mansion, the scenery is straight out of the horror movie playbook, right down to the ominous raven perched atop a branch of one of the many wild plants apparently reclaiming the land from the disused property. Nakagawa films the scene in a simple, elegant long shot, slowly tracking to follow as the front gate is opened and the characters enter; the effect is to make the audience feel as if they, too, are crossing a borderland into a different world, a slightly dreamy landscape where anything can happen. The effect is punctuated when the extended take is broken by a single insert closeup, as the wife sees a mysterious woman within a side building – only to find that the ghostly figure is gone when Kuzumi comes to see.

As effective as these touches are, the present day footage is a bit methodical in its buildup, as the ghost’s presence becomes gradually more intrusive, entering the premises, killing the family dog (off-screen), and eventually attacking the wife. Black Cat Mansion truly comes to life when it enters its extended flashback: the uncanny creepiness of the present day scenes are replaced by a overtly horrific melodrama that is more full-blooded and colorful – quite literally so, as the present days scenes are shot in blue-tinted black-and-white, while the period footage is in color.

Nakagawa immediately captures a convincing sense of a household living in fear of its temperamental master. There is an awful sense of inevitability as the events build to the murder and rape, reaching an emotional crescendo as the blind mother begs the pet cat to be her avenger, then takes her own life, after which the cat dutifully licks up the dead woman’s blood. The revenge that ensues is bizarre to say the least, with the actual cat soon replaced by a human with cat-like features, who sows mayhem and discord, leading to the deaths of not only the guilty lord but of innocent victims as well.

The makeup of the Ghost Cat appears slightly absurd to modern eyes, but it works well enough in longshot and shadows; some of the best scenes feature the character silhouetted against translucent screens. The action uses some simple camera tricks to create bizarre imagery: jump-cuts and reverse motion imbue the vengeful cat with supernatural powers. The matter-of-fact impact of these simple effects adds a touch of low-key believability to the otherwise unbelievable scenes.

The makeup of the Ghost Cat appears slightly absurd to modern eyes, but it works well enough in longshot and shadows; some of the best scenes feature the character silhouetted against translucent screens. The action uses some simple camera tricks to create bizarre imagery: jump-cuts and reverse motion imbue the vengeful cat with supernatural powers. The matter-of-fact impact of these simple effects adds a touch of low-key believability to the otherwise unbelievable scenes.

SPOILERS: With the back story filled in, the film returns to the events at the mansion, where the wife suffers a final attack before the hiding place of the murdered samurai’s body is revealed. Black Cat Mansion then returns to the opening scene at the hospital, where Kuzumi’s wife appears and asks to adopt the cat we heard meowing earlier. The return to normalcy offers a refreshing sigh of relief after what came before, but the wraparound feels a bit like the opening and closing footage of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), which used a similar structure to stitch a happy ending onto what had been intended as a pessimistic story. How did Mrs. Kuzumi survive the final attack, which apparently left her dead? Was the ghost cat exorcised by the revelation of the hidden body? Apparently so, but the film is not saying for sure. Viewers simply have to accept the ending as if emerging from the depths of a nightmare, back to a waking world where the past truly has been laid to rest, and life can go on with no residual fear of innocuous felines. END SPOILERS.

Black Cat Mansion is not a masterpiece that will sway the uninitiated. It is, however, a fine example of well-executed genre material, handled with serious intent and dedicated craftsmanship. Fans of old-fashioned horror looking for something beyond the standard list of classics should be satisfied, as should anyone with an interest in cult Japanese cinema, especially cineastes seeking the roots of modern J-horror (for example, with his feline yowl, Toshio from the Ju-On films is clear descendant of the ghost cat genre). Even cat lovers may get a kick out of the lengths to which a beloved pet will go to right the wrongs inflicted on its master and mistress. A dog may be man’s best friend; a cat, however, is a ruthless undead avenger.

Tag: scaredy cats

Tales of Terror: A CFQ 50th Anniversary Spotlight Podcast – 3:10

With no new horror, fantasy, or science fiction films opening this weekend, Cinefantastique stalwarts Lawrence French and Steve Biodrowski keep their Sense of Wonder alive by turning the clock back five decades for a retrospective celebration of TALES OF TERROR (1962), producer-director Roger Corman’s fourth film inspired by the work of Edgar Allan Poe. With a witty screenplay by Richard Matheson (THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN), and a cast including Vincent Price, Peter Lorre and Basil Rathbone, this three-part anthology serves up the expected chills and thrills, along with a perhaps unexpected dose of merriment, in MORELLA, THE BLACK CAT, and THE CASE OF M. VALDEMAR. The result is a classic example of 1960s terror cinema, colorful and atmospheric, with impressive art direction by Daniel Haller, beautifully captured by cinematographer Floyd Crosby, with an ethereal score by Les Baxter.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

So listen in as Steve and Larry open the vault to exhume the buried behind-the-scenes secrets and the arcane aesthetics of this popuri of Poe. The result is a scintillating CFQ Spotlight podcast, which answers the immortal question: What the hell happened to that missing limbo scene?

So listen in as Steve and Larry open the vault to exhume the buried behind-the-scenes secrets and the arcane aesthetics of this popuri of Poe. The result is a scintillating CFQ Spotlight podcast, which answers the immortal question: What the hell happened to that missing limbo scene?

[serialposts]

The Black Cat (2005) – DVD Review

This no-budget piece of worthless shot-on-video drek seems to exist only to prove one depressing proposition: no matter how much you think you have plumbed the bottom of the barrel, the barrel goes yet deeper still. Writer-producer-editor Serge Rodnunskytakes the basic outline of Edgar Allan Poe’s story and turns it into what at first looks like a TV cop show, with a female detective questioning a husband whose wife and child have gone missing. Hubby, apparently, had been going on one too many benders lately and taking it out on the family’s pet cat, but as the all-too-familiar – and extremely thin – storyline moves on, Rodunsky desperately throws in some pseudo-David-Lynch material, in which the detective visualizes herself in the suspects shoes. Is she psychic or just hallucinating – and does it really matter when the whole gambit is just an excuse for a girl-on-girl shower scene? (Don’t get too excited – the action here is just as boring as everything else in the film.) It all builds up to a lame double-twist conclusion that will have you shaking your head in exasperation (assuming you can rouse yourself from your coma long enough to uncramp your finger from the fast-foward button).

This no-budget piece of worthless shot-on-video drek seems to exist only to prove one depressing proposition: no matter how much you think you have plumbed the bottom of the barrel, the barrel goes yet deeper still. Writer-producer-editor Serge Rodnunskytakes the basic outline of Edgar Allan Poe’s story and turns it into what at first looks like a TV cop show, with a female detective questioning a husband whose wife and child have gone missing. Hubby, apparently, had been going on one too many benders lately and taking it out on the family’s pet cat, but as the all-too-familiar – and extremely thin – storyline moves on, Rodunsky desperately throws in some pseudo-David-Lynch material, in which the detective visualizes herself in the suspects shoes. Is she psychic or just hallucinating – and does it really matter when the whole gambit is just an excuse for a girl-on-girl shower scene? (Don’t get too excited – the action here is just as boring as everything else in the film.) It all builds up to a lame double-twist conclusion that will have you shaking your head in exasperation (assuming you can rouse yourself from your coma long enough to uncramp your finger from the fast-foward button).

Needless to say, the essentials of Poe’s tale – which is really about how a once-good person can bring about his own self-destruction by surrendering to his darker nature – is lost in the mix, and the significance of the titular black cat – a symbol of guilt that returns after its apparent death to remind the killer of his crime – is eclipsed by all the extra-added nonsense.

As for production values, there are none. The video photography is not bad, but the handheld camerawork frequently looks amateurish. The performers might be competent with decent material, but the pacing is excrutiatingly slow – with long, long, long moments that leave the actors utterly unable to fill up the screen time with anything interesting. The results are supposed to register as heavy drama, but they look like a bad soap opera or a video recording of an actor’s workshop gone wrong. (As someone on MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER once said, “This is an improv that just went nowhere.”)

Ultimately, this is not even a step above a home movie, lacing even the youthful enthusiasm of a student film. How it got a home video release is a real mystery; this wouldn’t even be worth seeing for free on YouTube.

Black Cat, The (1934)

No monsters but lots of atmosphere, this is a classic of the genre.

Eschewing many standard genre elements of its era, THE BLACK CAT is barely a horror film in the traditional sense, and it has even less to do with Poe than 1932’s MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE (which had also starred Lugosi). Nevertheless, this original scenario concocted by director Ulmer and writer Ruric is more than strong enough to earn this film a berth among the 100 Best Horror Films Ever Made.

Set mostly in a “House of Doom,” (the film’s title in England), which was built by an architect on the ruins of the fortress he sold out to the enemy during the First World War, the film has a very contemporary air, thanks to its (for the time) futuristic set design. Although not much actually happens, a subtle aura of perversity imbues the abode with an intangible but palpable horror, much like Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” (The overseas title hints at this connection.)

Conceiving the picture in an effort to capitalize on the success of DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN (both 1931), Universal Pictures pitted their reigning Kings of Horror, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, against each other in a battle of the Terror Titans. The story is basically a revenge tale, with Lugosi as Vitus Verdegast, returning to avenge himself on the architect (Karloff) who betrayed him and countless others during the war, and then married Verdegast’s wife (and later his daughter, too!) while Verdegast was being tortured in a prisoner of war camp.

Karloff, whose most famous horror role (as Frankenstein’s monster) was laced with patho, is excellently sinister here as the unrepentant and totally evil Satanist (who keeps his dead wives on display in glass cases in his basement). David Manners (an old hand at this kind of thing, since appearing in DRACULA and THE MUMMY) and Jaqueline Wells provide solid support as the innocent, honeymooning couple caught up in the conflict.

But the real coup lies in casting Lugosi as the nominal hero, which yields wonderful results, because his character is as unhinged as the villain. Locked in mortal combat, the only thing that separates him from his adversary is that he still has some concern for the innocent victims caught in the crossfire. Other than that, we are asked to identify with him, even as he finally loses all restraint and flays his tormentor alive!

Some elements are thrown in more or less gratuitously. Poe`s feline shows up long enough to justify the film’s American title and to help explain Verdegast’s delayed vengeance (his phobic reaction prevents him from killing his enemy at a crucial point). Diabolism and mysticism are thrown in to secure the film’s place in the genre (Karloff’s character is also a practising Satanist.)

But mostly the film is about the mortal struggle of two characters past all normal human boundaries of pain and suffering. The real horror is that of souls gone dead because of real-life atrocities of World War One. (At one point, when the yound lead is unable to phone for help, Karloff cackles, “Did you hear that, Vitus? The phone is dead! Even the phone is dead!”) This is probably the first film to make a direct connection between the real horrors of that war and the imaginary horrors it inspired on the silver screen.

There are some flaws, many apparently due to post-production tinkering. In several cases, lines have obviously been dubbed to help the audience understand what’s happening. In some cases, long shots that were intended to play without dialogue have voices issuing from mouths that are not moving. In two brief cases, we hear different actors’ voices coming from Karloff or Lugosi.

Also, the film’s almost operatic approach sometimes seems a bit heavy-handed. The music score (patched together from classical pieces) underlines the action with no pretense of subtlety, blaring ominously whenever Karloff enters a scene. There’s even an amusing moment in the second half of the film when two officials show up to ask some questions: even before they open their mouths, the music lets us know they’re on hand to provide some comic relief (they get into a pointless argument about which of their hometowns the honeymooning couple should visit).

But these minor flaws are trivial compared to the overall effectiveness. With no monster and little conventional suspense, this is nevertheless an extremely unusual and effective horror film that seeks to disturb on a deeper level. The music score may be a bit overemphatic for today’s viewers; otherwise, director Edgar G. Ulmer`s film is a perverse classic, tinged with hints of taboo subjects (necrophilia, incest) that still evoke a chill.

THE BLACK CAT (a.k.a. HOUSE OF DOOM, 1934). Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer. Screenplay by Peter Ruric; screen story by Ruric & Ulmer, suggested by the Edgar Allan Poe tale. Cast: Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, David Manners, Jacqueline Wells, Lucille Lund.

Cat with Jade Eyes (1977) – Film & DVD Review

This is a misleadingly titled giallo thriller in the tradition of Dario Argento’s THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE, FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET, and CAT O’NINE TAILS. Director Antonio Bido also borrows several stylistic tropes from Argento, particularly from DEEP RED: harsh violence; point-of-view shots; a repetitive, insistent main theme performed with a pop music arrangement instead of a traditional symphonic score. Consequently, CAT WITH JADE EYES (known in the U.S. as WATCH ME WHEN I KILL) is too derivative to stand on its own four furry paws, but it has enough feline grace to thrill fans of the form.

This is a misleadingly titled giallo thriller in the tradition of Dario Argento’s THE BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE, FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET, and CAT O’NINE TAILS. Director Antonio Bido also borrows several stylistic tropes from Argento, particularly from DEEP RED: harsh violence; point-of-view shots; a repetitive, insistent main theme performed with a pop music arrangement instead of a traditional symphonic score. Consequently, CAT WITH JADE EYES (known in the U.S. as WATCH ME WHEN I KILL) is too derivative to stand on its own four furry paws, but it has enough feline grace to thrill fans of the form.

The story begins with a pharmacist being murdered. A nightclub dancer named Mara (Paola Tedesco) tries to enter the pharmacy, but a voice inside tells her the store is closed. When she later realizes that the voice belongs to the murderer, she enlists the aid of her boyfriend Lukas (Corrado Pani) instead of relying on the police. Coincidentally, an acquaintance of theirs is receiving threatening phone calls from the same unidentified voice. As the bodies pile up, suspicion initially turns upon a recently released convict – the victims sat on his jury – but later evidence points the amateur investigation in another direction, having to do with a grim secret related to the past. Continue reading “Cat with Jade Eyes (1977) – Film & DVD Review”

Corpse Grinders (1972) – Film & DVD Review

This ’70s exploitation sleaze has a single virtue, but it is one not to be underestimated: it is so ridiculous that one cannot take it seriously. Whether intentional or not (director Ted V. Mikels claims he intended a spoof of horror films), the result is that all of the myriad faults of THE CORPSE GRINDERS (silly scripting, bad acting, cheap sets, dingy photography) become part of the entertainment value, turning the film into a campy laugh riot.

The story follows a doctor and his nurse-girlfriend, investigating the death of a woman who was apparently killed and partially eaten by her pet cat. Working on the questionable theory that domestic felines can acquire a taste for human flesh (as tigers are erroneously said to do in the wild), the amateur detectives follow a trail that leads them to a cat food company. It turns out that Continue reading “Corpse Grinders (1972) – Film & DVD Review”

Scaredy Cats: The Grudge (2004)

Cats are the perfect international horror movie stars. Like the genre itself, they make their impact with visuals, not dialogue, which is why horror travels well from country to country. A unique example of this is THE GRUDGE, an American remake of the 2003 Japanese production JU-ON: THE GRUDGE. Remaking a Japanese horror film had previously been successfully accomplished with 2002’s THE RING, but in this case the American version retained the original director, some of the actors, the Japanese setting – and of course the memorable cat-and-ghost-boy combo that sent shivers down so many spines. Continue reading “Scaredy Cats: The Grudge (2004)”

The Man and the Monster (1958) – Film & DVD Review

Fine technical craftsmanship and solid performances fight a losing battle with rampant stupidity in this entertaining Mexican horror film, which is alternately atmospheric and silly. The story follows a reporter named Ricardo (played by the film’s producer, Abel Salazar) who comes to a small town seeking an interview from Samuel (Enrique Rambal), a world-famous pianist who inexplicably abandoned the concert stage. Ricardo arrives in town just in time to find a blond woman who has been gored to death by some kind of monster inside the house where the pianist lives with his mother Cornelia (Ofelia Guilmain) and his young pupil Laura (Martha Roth). Despite the fact that the locals seem to have a superstitious dread of the place, the police see no reason to make any connection between the dead woman and Samuel. Ricardo makes little headway into the mystery, but a flashback eventually reveals that Samuel offered his soul to the Devil in exchange for becoming the world’s greatest pianist. He then killed his rival Alejandra (also Roth) and keeps her body locked in the closet of his paino room. There is a catch, however; when Samuel plays the piano, he turns into a hairy monster. Continue reading “The Man and the Monster (1958) – Film & DVD Review”

Catwoman (2004) – DVD Review

This semi-sequel of sorts to BATMAN RETURNS spins the popular Catwoman character off into her own film – the would-be beginning of a franchise that failed to materialize, thanks to dismal box office returns. An almost unmitigated disaster, this major studio production with a major star in the lead (the Oscar-winning Halle Berry) comes across like a direct-to-video production, complete with ultra lame computer-generated effects and clueless direction by someone who signs himself “Pitof” (whose previous experience lay mostly in directing visual effects – which makes the lousy work on display here all the more confusing). The film feel like a low-budget knock-off, something Warner Brothers pumped out on the cheap, hoping the sight of Berry in her Catwoman costume would suck in foolish ticket buyers, regardless of the amateurish quality. Continue reading “Catwoman (2004) – DVD Review”

This semi-sequel of sorts to BATMAN RETURNS spins the popular Catwoman character off into her own film – the would-be beginning of a franchise that failed to materialize, thanks to dismal box office returns. An almost unmitigated disaster, this major studio production with a major star in the lead (the Oscar-winning Halle Berry) comes across like a direct-to-video production, complete with ultra lame computer-generated effects and clueless direction by someone who signs himself “Pitof” (whose previous experience lay mostly in directing visual effects – which makes the lousy work on display here all the more confusing). The film feel like a low-budget knock-off, something Warner Brothers pumped out on the cheap, hoping the sight of Berry in her Catwoman costume would suck in foolish ticket buyers, regardless of the amateurish quality. Continue reading “Catwoman (2004) – DVD Review”

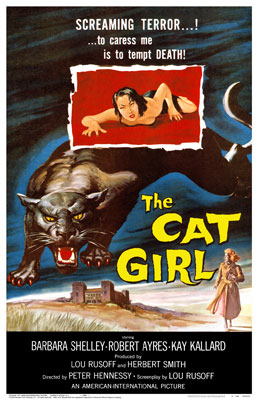

Cat Girl (1957) – A Retrospective Review

The little, low-budget opus belatedly attempts to cash in on CAT PEOPLE, but it has little of the subtlety and none of the style of the 1942 Val Lewton production. In a strange way, CAT GIRL seems more old-fashioned than its model: the limited production values, melodramatic tone, and outdated attempts at spooky atmosphere suggest a cheap British rip-off of Universal’s 1930s horror classics. (Ernest Milton, as the demented Uncle Edmund, comes across like a poor man’s version of Ernest Thesiger – the actor who camped up James Whale’s THE OLD DARK HOUSE and BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.) Released a few months after CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN – Hammer’s bold color reinvention of the horror genre – CAT GIRL must have seemed like a dated relic in its own time. Decades later, it earns some points for effort, but its most significant claim to importance lies in the casting of Barbara Shelley – a fine actress who would give strong performances in several Hammer horror films (such as THE GORGON). Continue reading “Cat Girl (1957) – A Retrospective Review”

The little, low-budget opus belatedly attempts to cash in on CAT PEOPLE, but it has little of the subtlety and none of the style of the 1942 Val Lewton production. In a strange way, CAT GIRL seems more old-fashioned than its model: the limited production values, melodramatic tone, and outdated attempts at spooky atmosphere suggest a cheap British rip-off of Universal’s 1930s horror classics. (Ernest Milton, as the demented Uncle Edmund, comes across like a poor man’s version of Ernest Thesiger – the actor who camped up James Whale’s THE OLD DARK HOUSE and BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.) Released a few months after CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN – Hammer’s bold color reinvention of the horror genre – CAT GIRL must have seemed like a dated relic in its own time. Decades later, it earns some points for effort, but its most significant claim to importance lies in the casting of Barbara Shelley – a fine actress who would give strong performances in several Hammer horror films (such as THE GORGON). Continue reading “Cat Girl (1957) – A Retrospective Review”