As part of our weekend tribute to the late special effects director Sadamasa Arikawa, here is the Japanese trailer for SON OF GODZILLA (1967) – a cute and cuddly kiddie flick in which the formerly terrifying radioactive reptile is revealed to be an old softie at heart, a caring parent who looks after junior, protects him from giant mantisis and a colassal spider, and teaches him out to breath radioactive steam from his lungs. One peculiarity of the trailer that will surprise viewers familiar only with the American release of the film, is that it contains comic book-style word balloons for Godzilla’s son, known as Minya. I can’t imagine what the little tyke is supposed to be saying, but I am dying to find out.

Tag: Sadamasa Arikawa

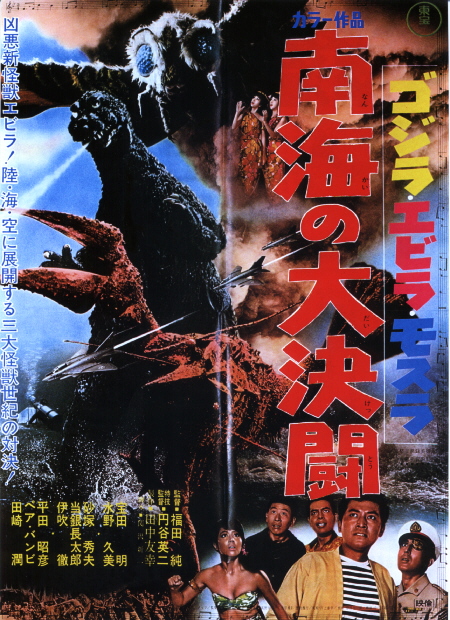

Destroy All Monsters – U.S. Theatrical Trailer

As part of our weekend tribute to the late special effects director Sadamasa Arikawa, here is the U.S. theatrical trailer for DESTROY ALL MONSTERS – the memorable Toho production in which Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and all of Earth’s other monsters team up for a non-stop destruction derby involving invading aliens trying to take over the Earth. The trailer does a good job of showing off the film’s unconvincng but colorfully entertaining effects, and it includes a blooper when the monster Gorosaurus is mis-identified as Baragon (a problem that exists in the film as well).

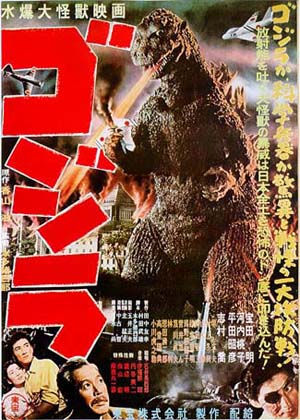

Sense of Wonder: A Mini-Tribute to Godzilla's Sadamasa Arikawa

If you want to draw eyeballs to an online magazine, you have to fill it with stuff that is new, new, new, but one of the defining aspects of Cinefantastique was its love for classics, expressed in frequent cover stories and retrospective articles. We like to keep that tradition alive at Cinefantastique Online, especially on the weekend, when there is less news to fill our webpages. With that in mind, we offer today’s tribute to one of the un-sung heroes of Japanese giant monster movies, Sadamasa Arikawa.

Sadamasa Arikawa, who died in September of 2005, was one of the last living people who worked behind the scenes on the original GODZILLA way back in 1954. He worked on the special effects for numerous other Japanese science fiction films throughout the 1960s, eventually ascending to the role of special effects director. Following in the footsteps of Eiji Tsuburaya, who retained credit as “supervisor” on the films for which Arikawa directed special effects, Arikawa never stepped out from under his legendary mentor’s giant shadow, but he did contribute some fine work of his own.

Arikawa began his career as an uncredited cameraman for the special effects crew on GOJIRA, that 1954 rampaging reptile flick that was re-edited, re-shot, and released in the U.S. (with much of its anti-nuclear message muted) as GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS in 1956. Arikawa became the protoge of Eija Tsuburaya, the man who directed the special effects in GOJIRA and countless other kaiju films produced at Toho Studios. After Tsuburaya started his own production company and began focusing his attention on television shows like ULTRAMAN, Arikawa graduated to directing the special effects for such films as GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER.

By the time Arikawa took over the special effects department, the budgets for the Godzilla films had dropped, so his work often compares unfavorably with that of Eiji Tsuburaya. There was also a studio-mandated trend toward making the monsters more human and less frightening, in order to appeal to younger viewers. Yet Arikawa managed to turn out some colorful and engaging (if not always convincing) effects for SON OF GODZILLA and DESTROY ALL MONSTERS.

In 2000, Arikawa came to the United States to take part in a festival of Japanese fantasy and horror films. He talked at length about his work on GOJIRA and SON OF GODZILLA. He was a lively and engaging speaker, even with the burden of having to answer questions through an interpreter, and he seemed genuinely touched by the fact that so many people and shown up at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood just to see a screening of an old film he had worked on 46 years previously:

“I would like to thank everyone for watching the film. It’s been [nearly] fifty years, and it’s a completely different point of view watching the film today than it was then. I can feel the warm appreciation from the audience — and felt for the first time such apreciation — so I would like to thank everyone for watching the film and enjoying it so much.”

These words are like music to our ears. If there is one thing we believe at Cinefantastique Online, it is that warm audience appreciation can exend beyond the years and beyond the generations. Cinematic styles come and go; new techniques become antiquated. Once popular films are either relegated to the dustheap of history, or they survive as classics (or at least cult films). So, we offer this affectionate appreciation of the work of Sadamasa Arikawa:

Destroy All Monsters (1968) – Kaiju Review

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS is probably the last well-regarded entry in the original Godzilla series. By this time, all serious threat of the monsters had disappeared; recognizing this, director Ishiro Honda (who had helmed the original GODIZLLA in 1954 and many of the subsequent sequels) opted for a fast-paced action-adventure roller-coaster thrill ride that was seldom scary but always entertaining. Co-scripting with Takeshi Kimura (RODAN), Honda used a slim, familiar story (aliens use monsters as weapons in a war against the Earth) to string together as many effects sequences as possible, creating a memorably colorful confection.

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS is probably the last well-regarded entry in the original Godzilla series. By this time, all serious threat of the monsters had disappeared; recognizing this, director Ishiro Honda (who had helmed the original GODIZLLA in 1954 and many of the subsequent sequels) opted for a fast-paced action-adventure roller-coaster thrill ride that was seldom scary but always entertaining. Co-scripting with Takeshi Kimura (RODAN), Honda used a slim, familiar story (aliens use monsters as weapons in a war against the Earth) to string together as many effects sequences as possible, creating a memorably colorful confection.

Basically, it’s MONSTER ZERO (a.k.a. INVASION OF ASTRO-MONSTER) all over again, except this time, instead of just Godzilla, Rodan, and King Ghidorah, we also get Mothra, Anguirus, Gorosaurus, Manda, Kumonga (a.k.a. Spiga, the giant spider), Varan, Baragon and Minya, Godzilla’s son. DESTROY ALL MONSTERS lacks MONSTER ZERO’s slightly more adult storyline and the clever banter between Nick Adams and Akira Takarada, but it delivers much more monster action. True, some of the monsters make little more than cameo appearances, but the big stars get plenty of screen time, and second-stringers Anguirus, Gorosaurus, and Manda get a few moments to shine as well.

Before DESTROY ALL MONSTERS, the previous two films in the series, GODZILLA VS THE SEA MONSTER and SON OF GODZILLA, had shifted gears, with director Jun Fukada and composer Masuro Sato replacing the Ishiro Honda and composer Akira Ifukube. The results were light-hearted and fun, offering a clear change of pace for the series.

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS sees a return to form, with the old director-composer team back in place, with Ifukube offering another example of his impressive monster movie music, by turns ominous, mysterious, and rousing – quite a contrast to Sato’s jazz-pop stylings (which were more suited to something like GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER, which stuck the monsters in the middle of what looked like a spy adventure).

Also notable is the absence of screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa, one of the chief architects of transforming Godzilla from villain to hero. It would be going too far to say that his absence signals a more serious approach in DESTROY ALL MONSTER, but the screenplay by Honda and Kimura definitely avoids the juvenile tone of SON OF GODZILLA.

Instead, DESTROY ALL MONSTERS is a true movie-movie. It takes itself seriously only in the sense that it does not adopt an attitude of campy condesension towards its monster-filled alien-invasion scenario. The events are presented in a straight-forward way that is an almost perfect realization of any ten-year-old boy’s dream of the most awesome movie adventure ever, loaded with heroic heroes piloting rocket ships to the moon and back while battling an evil race that has turned all of Earth’s monsters loose in one cataclysmic attack.

Honda directs DESTROY ALL MONSTERS with brisk efficiency, using the widescreen image to show off the sets and letting the actors have a ball. A free-for-all shoot out between astronauts and aliens has the heroes waving guns around not in manner designed to actualy hit a target but simply to look good on camera. In a way, this is the apex of ’60s cinema, back when movies like OUR MAN FLYNT were all about having a good time with gadgets and explosions, no matter how unlikely the storyline.

Fortunately, Honda offers more than just monsters and mayhem; there are even a few intriguing moments that border on the subtle. A long interrogation with a human taken over by aliens holds attention because the interrogation subject (Yoshio Tsuchiya) always seems on the verge of breaking his silence – but he never does. Outside on the beach, another human controlled by aliens – this one a woman – walks along a beach in high heels; the sight of those high-fashion stilettos sinking into the sand is almost surreal.

And in one of the most memorable sequences of any giant monster movie, this same alien-controlled woman walks, calm and unconcerned, amidst the panic that erupts when sirens announce an imminent attack on Tokyo. The stark contrast between the mad, rushing crowds and her serence face, indifferent to (or perhaps even eager for) the monsters’ arrival, is a wonderful sight to behold.

Special effects director Sadamasa Arikawa (working under the “supervision” of Japanese effects pioneer Eiji Tsuburaya) delivers several memorable sequences in DESTROY ALL MONSTERS. The initial attacks on Moscow, Paris, and New York go by too fast, but theyleave you wanting more. The aforementioned attack on Tokyo is one of the great sequences of its type, featuring a coordinated assault by four monsters (Godzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and Manda), with some cleverly timed action (e.g., the serpentine Manda cracks a bridge in the foreground simultaneously with Godzilla’s blasting a building with his radioactive breath).

Of course, Arikawa’s effects are far from convincing, but that becomes part of the charm. By this time, Toho had given up almost any pretense of making you believe in their menagerie of monsters and had developed their own particular aesthetic, in which acrobatic flair and flashy pyrotechnics outweighed believability. Consequently, even if the vision of space travel, rockets, and lunar landscapes in DESTROY ALL MONSTERS looks quaint compared to 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY – well, the unreality suits the storyline.

Keeping with this tradition, the final all-out assault of Earth’s monsters against the alien’s ace in the hole, King Ghidorah, is as entertaining a battle as ever put on screen, even though the wires show. The action deliberately defies physics, opting for a World Wrestling aesthetic in which monsters supposedly weighing thousands of tons effortlessly leap, jump, and fly with acrobatic flair; at one point, Gorosaurus even springs high off the ground to deliver a kick to Ghidorah’s back. Also as in wrestling, bodies are slammed, kicked, punched, and pummelled, with little if any real damage ever done – it’s all for show, not effectiveness. And Arikawa cannot resist the urge to anthropomorphize the monsters, as when Minya shields his eyes to avoid seeing King Ghidorah drop Anguirus to the ground (a shot deleted by AIP when the film played in U.S. theatres).

Despite all this, Ishiro Honda and Sadamasa Arikawa combine their talents to create one scene in DESTROY ALL MONSTERS that offers at least an echo of genuine suspense: when the heroes search for the aliens’ hidden lair on Earth, they are interrupted by Godzilla and Anguiras, acting as enormous guard dogs. Unlike many of Toho’s then-current films, which tended to shoot the monsters at eye level, undermining the sense of size, this sequence presents a good combination of camera angles, from the human perspective looking up and from the monster perspective looking down, including some effective composite shots that integrate humans with monsters in the same frame. For a brief moment, you almost remember what it was like to be frightened at the prospect of being crushed by something so huge that it would barely feel you under its toes.

In the end, DESTROY ALL MONSTERS is too slim in its storyline, too thin in its characterizations, to be considered a truly great film. It is not as impressive as the original GODZILLA, and it is not as hip as MONSTER ZERO. But for the ten-year-old living inside us all, it is entertainment of the most awesome sort.

TRIVIA

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS introduced the concept of Monster Island (here called “Monster Land” in the English dubbing), an island where all of Earth’s monsters had been gathered and kept locked up for study. Future Godzilla films would use Monster Island as a lazy way to re-introduce the monster without having to worry too much about continuity.

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS features the return appearance of Anguirus, the very first monster to fight Godzilla, way back in 1955’s GODZILLA RAIDS AGAIN (a.k.a. GIGANTIS THE FIRE MONSTER). Basically an oversized dinosaur (an ankylosaurus), Anguirus would go on to appear in GODZILLA VS. GIGAN and GODZILLA VS. MECHAGODZILLA in the 1970s. On the basis of these few appearances, Anguirus inexplciably became a favorite among some fans, who eagerly awaited his return when the Godzilla franchise was revived in the 1990s. Anguirus finally reappeared in the “last” Godzilla film, GODZILLA: FINAL WARS, a virtual remake of DESTROY ALL MONSTERS.

Directors Contrad Vernon and Rob Letterman cited DESTROY ALL MONSTERS as an influence on their 2009 animated film MONSTERS VS. ALIENS: “We watched it three or four times,” says Vernon, who was inspired by the plot involving mangy monsters freed from an island prison by galactic invaders. “We even have our villain, Gallaxhar, use the command, ‘Destroy all monsters.’”

INDEPENDENCE DAY (1996) also bears structural similarities to DESTROY ALL MONSTERS. The filmmaking team of Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin would go on to do the 1998 American version of GODZILLA.

DUBBING DIFFERENCES

Unlike most of the Toho giant monster movies, DESTROY ALL MONSTERS reached U.S. shores relatively unchanged, except for being dubbed into English. Ironically, Toho had created an English dub of the film to increase its export value, but the U.S. distributor, American International Pictures, commissioned a new dialogue track, featuring the likes of Hal Linden (television’s BARNEY MILLER).

The AIP dub rewrites some of the lines and provides better voice acting. This version was seen in theatres and on television in the U.S., but it has not been available since the defunct AIP’s distribution rights lapsed. Currently available prints are of the Toho “International” version.

The dub on the International version of DESTROY ALL MONSTERS features a literal English translation of the Japanese dialogue, which does not always sound natural; the problem is aggravated by the weak vocal performances.

In at least one case, the International version’s audio track is superior. In the AIP dub, there is a lame line when a reporter watching the climactic battle near Mt. Fuji holds up his microphone and says, “I’ll turn up the sound so you can hear the monsters dueling to the death.” The Toho dub offers instead a memorable moment of high-camp comedy: “It’s horrible, ladies and gentlemen – listen to the monsters and their cries of sudden death!” This perhaps intentional echo of the “Oh, the humanity!” account of the Hindenburg disaster is capable of bringing the house down with laughter, should you ever be lucky enough to see DESTORY ALL MONSTERS in a theatre crowded with kaiju fans.

During the early montage of monsters attacking different cities around the globe, the International version offers newscaster voices overs doing very bad accents (Russian, French, etc) – an effect carried over to some extent in the AIP dub. (The original Japanese audio track has the voice-overs speaking in their native languages.)

The above-mentioned montage contains one of the more memorable film flubs in the Godzilla series. France’s Arc de Triomphe was supposed to be toppled by the burrowing monster Baragon (introduced in FRANKENSTEIN CONQUERS THE WORLD), but problems with the suit necessitated that Gorosaurus get the job instead. The dialogue was never changed, so the monster is erroneously identified as Baragon – a mistake carried over in the written text of the U.S. theatrical trailer.

DESTROY ALL MONSTERS (Kaiju Soshingeki [“Monster Invasion”], 1968). Directed by Ishiro Honda. Written by Ishiro Honda, Takeshi Kimura. Cast: Akira Kubo, Jun Tazaki, Yukiko Kobayashi, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Kyoko ai, Andrew Hughes, Chotaro Togin, Yoshifumi Tajima, Kenji Sahara, Hisaya Ito, Yoshio Katsuda.

Portions of this review originally appeared in “Godzilla Invades L.A.” in the December 1996 issue of Cinefantastique (Volume 28, Issue 6).

Son of Godzilla (1967): Kaiju Film Review

This film is from the goofy era when Godzilla was mutating from a radioactive menace into a lovable hero. The tone is definitely geared for younger viewers, and it’s impossible to take the proceedings seriously. And yet, SON OF GODZILLA is actually quite entertaining on its own juvenile level, filled with strong performances, exotic locations shooting, colorful special effects, enjoyable music, lots of action, and plenty of laughs.

This film is from the goofy era when Godzilla was mutating from a radioactive menace into a lovable hero. The tone is definitely geared for younger viewers, and it’s impossible to take the proceedings seriously. And yet, SON OF GODZILLA is actually quite entertaining on its own juvenile level, filled with strong performances, exotic locations shooting, colorful special effects, enjoyable music, lots of action, and plenty of laughs.

The story focuses on a group of scientists conducting experiments on an isolated South Seas island. Their initial test (an attempt to change weather) runs afoul of unexpected high-frequency interference – which turns out to be a telepathic cry for help from a mysterious egg that is unearthed by a group of giant preying mantises. The botched test creates a torrential downpour of contaminated rain that somehow enlarges the preying mantises even further. They break open the egg, revealing a baby Godzilla, but before they can kill it, the elder Godzilla arrives, responding to the signal that ruined the test. The scientists, along with a reporter who parachutes in, looking for a story, and an orphaned island girl, try to finish their experiments in spite of the monsters; the girl even feeds coconuts to the baby Godzilla, named Minya. But then things really get bad: a giant spider emerges from its rocky lair and engages in a life-or-death battle with the father-and-son dinosaurs. The scientists launch another test just before escaping on the life raft. As Godzilla and Minya finish off the spider, the test reverses the sweltering tropical temperature, resulting snowfall on the island. As a submarine surfaces to rescue the scientists, they see Godzilla and Minya huddle together, going into hibernation in the freezing cold.

Unlike the previous entry in the series, GODZILLA VS THE SEA MONSTER, which asked you to check your brain at the door and enjoy a spy-movie-action no-brainer, SON OF GODZILLA only asks that you enjoy the film as fun-filled family entertainment. The image of Godzilla as paternal protector is completely at odds with the monster’s radioactive origins, but if you can jump that mental hurdle, SON OF GODZILLA is actually quite a bit better than its most obvious equivalent, the silly SON OF KONG (1933).

SON OF GODZILLA’s light-hearted tone is underlined by the music of Masuro Sato (who had previously scored GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER). His jazzy, upbeat themes suggest a cool ’60s action flick, abandoning the ponderous, serious tone of Akira Ifukube, who had scored most of the previous Godzilla films. Likewise, director Jun Fukuda goes for a fast-pace, with an emphasis on the entertaining action rather than sober scares. This approach, combined with colorful production design, creates a sort of artificial movie atmosphere that is almost the cinematic equivalent of a comic book – it’s fun to look at, even if you don’t believe it.

The special effects are a step up from the previous film. At a time when Toho studios was shaving budgets by moving away from expensive composite photography, the film is filled with special effects shots that combine live-action with the miniature monsters to great effect. The work may not be convincing (in fact, wires are often visible operating the mantises and the spider, which are large marionettes, not actors in suits), but it does establish a style that becomes its own justification, creating not a picture of reality but a make-believe world filled with scary dangers (scary to kids, that is). Special effects director Sadamasa Arikawa (taking over for Eija Tsuburaya, who had moved on to television work on series like ULTRAMAN) expertly choreographs the monster actions and battles – the movements of the giant mantis and spider that Godzilla fights are all impressive.

The design work for the insects and the arachnid are quite good. Unfortunately, the younger Godzilla looks nothing like his famous parent: he’s roly-poly and cute – obviously designed to enchant kids. Even worse, the Godzilla suit in this film is infamous among fans for being one of the worst in the series—with big white eyes that give a Muppet-type look to the king of the monsters, apparently in an attempt to make him more human and likable. Even with these changes, there is little resemblance to his son, who is mostly used to comic effect.

The design work for the insects and the arachnid are quite good. Unfortunately, the younger Godzilla looks nothing like his famous parent: he’s roly-poly and cute – obviously designed to enchant kids. Even worse, the Godzilla suit in this film is infamous among fans for being one of the worst in the series—with big white eyes that give a Muppet-type look to the king of the monsters, apparently in an attempt to make him more human and likable. Even with these changes, there is little resemblance to his son, who is mostly used to comic effect.

Strangely, the film remains enjoyable in spite of its problems. By this time in the series, the serious science-fiction trappings of 1954’s GOJIRA had long been abandoned in favor of a fantasy approach. However, if you’re willing to suspend disbelief, the results are amusing. This is definitely a camp movie, but a thoroughly enjoyable one, and the scene of Godzilla and son going into hibernation together as the snow covers them is surprisingly effective.

FAVORITE SCENES

At one point, Godzilla attempts to teach Minya to use his radioactive breath, but the poor little tyke only blows smoke rings – until the angry parent stomps on his tail, causing the youngster to spew the desire radioactive halitosis. Shortly thereafter, Godzilla takes a nap, and Minya plays jump rope over his twitching tail!

In one excellent shot (beautiful to behold on a cinemascope movie screen), the live actors take cover behind a metalic structure in the foreground, while the giant spider walks from left to right through the miniature jungle in the background. The action is perfectly timed, the blend of full-scale and miniature elements is convincing, and the movement of the spider is perfect.

TRIVIA

Haruo Nakajima, the man inside the Godzilla suit throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and into the ’70s, gets a rare screen credit for his performance in SON OF GODZILLA. Ironically, he is not in much of the film, appearing only in those scenes wherein Godzilla is seen rising out of the ocean near the beginning. (The old Godzilla suit seen in previous films was resued for this scene.) All of Godzilla’s scenes on land are performed by Seiji Onaka, a taller actor, in a new suit made to look less threatening. The reason for the casting change is that the titular Son of Godzilla is performed by a midget wrestler (“Little Man” Marchan), and it was necessary to get a taller actor in the Godzilla suit, so that there would be a greater distinction in height between Godzilla and his son.

This is the first film to use the phrase “Monster Island,” although in this case it is casually tossed off by a reporter to describe the fact that the tropical island is inhabited by a handful of monsters (giant preying mantises, a giant spider). In subsequent Toho films, Monster Island would specifically refer to an island where the the entire pantheon of monsters from previous films (Rodan, Mothra, etc) were gathered together.

On the original Japanese-language soundtrack, the spider is called Kumonga, and the giant mantises are called Karakuras. For the English-dubbed version, the monster’s names were changed to, respectively, Spiga and Gimantis.

SON OF GODZILLA (Kaijuto No Kessen: Gojira No Musuko[ “Monster Island’s Decisive Battle: Godzilla’s Son”]1967). Directed by Jun Fukuda. Written by Shinichi Sekizawa, Kazue Shiba. Cast: Tadao Takashim, Akira Kubo, Bibari Maeda, Akihiko HIrata, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Kenji Sahara, Kenichiro Maruyama, Seishiro Kuno, Seiji Onaka, Haruo Nakajima, “Little Man” Marchan.

Godzilla vs the Sea Monster (1966) – Kaiju Film Review

This is one of the silliest but also one of the more amusing Godzilla movies. The goofiness of the enterprise somehow becomes part of the entertainment value, resulting in a likable, fun-filled, fast-paced movie that is totally incredible but quite watchable.

This is one of the silliest but also one of the more amusing Godzilla movies. The goofiness of the enterprise somehow becomes part of the entertainment value, resulting in a likable, fun-filled, fast-paced movie that is totally incredible but quite watchable.

The story begins (in the original Japanese cut) with a family worried about a missing son. Some people go looking for him and wind up accompanied by a likable thief who recently pulled off a big heist. Their search takes them to a South Seas island, which is protected by Ebirah, a giant shrimp-like monster. As if this were not bad enough, the island is the secret base of an organization calling itself “Red Bamboo” that is planning to launch a campaign of world domination. As slave labor, they have been kidnapping villagers from a nearby island presided over by Mothra, the giant moth-like god; among the slaves is the missing son. After infiltrating the villains’ lair, our heroes discover Godzilla lying dormant in a cave. By stringing up some wire into a lightening rod, they manage to revive Godzilla when a storm comes by, sending down the necessary bolt of electricity. The giant radioactive reptile turns his destructive attention on the bad guys, destroying the Red Bamboo facilities. The villains set a self-destruct device to blow up the island and make their escape, but their island slaves have double crossed them, intentionally botching a batch of the Ebirah-repellant formula they are forced to manufacture; as a result, the giant shrimp smashes the Red Bamboo’s escape vessel. Godzilla kills the giant shrimp; then Mothra arrives just in time to rescue the islanders. Grateful for Godzilla’s help, the escaping people yell at him to jump off the island – which he does, just before it goes up in a nuclear blast.

The script by Shinichi Sekisawa eschews the city-stomping clichés that hard marked previous Godzilla flicks, in favor of an island setting, lending a new flavor to the film. With its SPECTRE-like secret organization plotting to take over the world, GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER feels almost like a James Bond film, and director Jun Fukuda treats it as such, featuring lots of fast-paced action and gunplay. Frankly, the whole thing is totally ridiculous, and yet somehow it manages to be colorful, exciting fun.

The cast seems to enjoy their roles, perhaps because several of them are playing against type. Akihiko Hirata (the noble, self-sacrificing scientist in the original GODZILLA) wears his eye-patch again, but this time he plays a strutting, uniformed villain – with appropriate gusto. Cast as a thief, Akira Takarada leaves behind the bland good-guy persona of his previous Godzilla appearances and actually brings off a feeling of daring and panache.

By this point in the series, the special effects had given up any pretense of being convincing, and the result is that Godzilla’s scenes often resemble something that might be called “Muppet Theatre.” The camera tends to be at eye-level, destroying any sense of size, and tracking and hand-held shots further undermine any illusion of an enlarged perspective, constantly reminding us that we are watching a man in a suit.

That said, the monster action is fun, in a juvenile way. Godzilla is almost totally anthropomorphic at this point. At one point, he flicks his finger along his nose after dispatching one opponent. In his battle with Ebirah, the giant shrimp winds up like a baseball pitcher before throwing a boulder, which Godzilla bats back with his head, like a soccer player. There are the usual jets on wires firing missiles, a scrawny vulture-like bird that shows up just enough to get torched by the Big G’s radioactive breath, and little kids get a big kick out of seeing Godzilla’s feet-first dive off a cliff into the ocean at the end.

It may be nonsense, but it is enjoyable nonsense for fans, especially younger ones. There can be no doubt that by this point Godzilla had completely mutated from his original purpose (as a walking metaphor for nuclear destruction). As such, this film has little appeal for serious science-fiction fans, but if you don’t mind checking your brain at the door, you may be surprised to find yourself having a very good time indeed.

FAVORITE SCENES

Our group of intrepid heroes, led by a likable thief, unlocks a vault-like door within the high-tech headquarters of the secret organization bent on world domination. They sneak inside – only to rush out again, as one yells, “Quick, get out – it’s a nuclear reactor!” Luckily, their close encounter with atomic energy leaves none of them suffering from radiation burns or sickness of any kind.

TRIVIA

This is the first film wherein Sadamasa Arikawa took over for Eija Tsuburaya as director of special effects. Unfortunately, the low-budget serves Arikawa poorly, and the effects are below par, even by the standards of Japanese fantasy films. In particular, the Godzilla suit is not a new one but a leftover from previous films. In some shots, the patchwork is visible – damage from the pyrotechnical abuse (miniature missiles, etc) has left noticeable damage.

The script, written when the Godzilla series was running out of gas, was originally intended as a vehicle for King Kong, hence the South Seas setting and the scene wherein Godzilla makes goo-goo eyes at a native girl. However, Toho studios could not secure the rights to the Kong character, so Godzilla was recast in the title role, apparently with little or no rewriting. (Note that Godzilla is revived with lightening – which had worked so well for Kong in Toho’s KING KONG VS. GODZILLA.) As a result, the film represents an almost complete break with the continuity established by the previous Godzilla films.

The English-dubbed American version of the film omits any verbal references to either “Red Bamboo” or “Ebirah.” Also, the film is extensively recut. Instead of beginning with a family worry about their missing son, the American cut begins with a small boat lashed by a storm while a giant lobster-like claw emerges from the depths. Although positioned to suggest that this is the missing son, the footage was moved up from later in the film, and represents a completely different character in a different boat (if you look closely, you can tell, because the name of the boat is visible). This version of the film was never released to theatres; instead, it was sold directly to television.

The film’s original Japanese title translates roughly as GODZILLA, MOTHRA, AND EBIRAH, THE HORROR OF THE DEEP. The shorter EBIRAH, HORROR OF THE DEEP was the international release title, used when Toho was shopping the film for foreign distribution.

This is one of several GODZILLA films that were released in Germany with a title change to include the word “Frankenstein.” Apparently, German film distributors thought this would increase the film’s commercial appeal. Contrary to some rumors, the German-language dubbing did not rename Godzilla as “Frankenstein.” Rather, the monsters that Godzilla fought were explained as creations of the infamous doctor.

GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER ( Gojira, Ebira, Mosura: Nankai no Daiketto [“Godzilla, Ebirah, Mothra – South Sea Battle”] 1966). Directed by Jun Fukuda. Written by Shinichi Sekizawa. Cast: Akira Takarada, Kumi Mizuno, Chotaro Togin, Hideo Sunazuka, Toru Watanabe, Toru Kbuki, Akihiko Hirata, Jun Tazaki, Ikio Sawamura, Haruo Nakajima.

Godzilla, Father & Son – Sadamasa Arikawa Interview

EDITOR’S NOTE: In this archive question and answer session, culled from personal appearances made at a Godzlla film festival in 2000, the late special effects expert discusses his work on Toho’s biggest monster, from the frightening original to the comic “Son of” Sequel.

Sadamasa Arikawa served under the legendary special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya, the man who created harrowing scenes of death and destruction in many Japanese science fiction films in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Arikawa began his career by working in an uncredited capacity as a camera operator on the special effects unit of the early kaiju classics as GODZILLA (1954), and he served in similar capicity on later films like RODAN (1957). After working his way up through the ranks, Arikawa (who was often credited on his films as “Teisho” Arikawa) eventually took over the position of special effects director, under the “supervision” of Tsuburaya, who focused his attention to television work in the mid-1960s. Arikaway directed special effects for several colorful and fun-filled films such as GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER (1966), SON OF GODZILLA (1967) and DESTROY ALL MONSTERS (1968).

Although interviewed through a translator during a visit to the American Cinemathque in Hollywood, Mr. Arikawa’s personality somehow managed to shine through the veil of translation, charming and entertaining listeners with his inflection and enthusiasm, even before his answers were rendered in words that his listeners could understand. Here are his memories of making the very first GODZILLA movie:

QUESTION: THERE’S A STORY THAT THERE WAS SOME TROUBLE WITH THE MINIATURE ELECTRICAL TOWERS THAT GODZILLA MELTS WITH HIS RADIOACTIVE BREATH.

Sadamasa Arikawa: Before I answer that question, I would like to thank everyone for watching the film. It’s been fifty years, and it’s a completely different point of view watching the film today than it was then. I can feel the warm appreciation from the audience — and felt for the first time such appreciation — so I would like to thank everyone for watching the film and enjoying it so much.

In those days, the science of making miniatures was very primitive. For example, everyone could see the boats and feel they were watching real boats. The boats were actually filmed in a small pool, and the feeling at the time was, “As long as the boats are floating, that should be good enough.” I feel everyone watching it can get a sense that the technology was primitive at the time we were filming it. But we were also trying to make a good project as well.

Toho Studios also felt it was time to be breaking new ground in movie technology. The war was over, and it was time to be moving in a new direction. There was a strong feeling on the part of the studio and the people involved that they wanted to break new ground and do something special with the film.

Seeing as we’re running out of time, I’ll get around to answering your question. [laughter from the audience] Getting back to the original question, it had a miniature set that was as detailed as possible — with, for example, electrical towers and apartment buildings, even down to laundry hanging out to dry on the buildings. You may be familiar with this story, but the electrical towers had wires that needed to be electrified, using fuses. In order to make the sense of perspective, the wires toward the back of the set, the ones that were to appear father away, used smaller fuses, and the ones that were closer used larger fuses, so that when the wires were electrified and electricity was traveling along the line, you would have the size of [sparks] on the wires in accordance with their appropriate distance.

The set was prepared when it was cooler, but once the lights were turned on, it heated up quite a bit. As a result of the heat, the wires started to sag. Unfortunately, that meant we would have to restring the wires to get them to look like electrical wires, because they were sagging too much. So the process of making this film was complicated by the fact that we had to continually rebuild the set as we went on.

HOW LONG DID IT TAKE TO BUILD THE MINIATURES, AND HOW LONG DID IT TAKE TO DESTROY THEM?

Sadamasa Arikawa: A very good question. Of course we were building models pretty much for our own satisfaction, until the models became very intricate, elaborate, and durable, to the point where it became difficult for Godzilla to destroy them. So we changed our method of building models. As opposed to building them up, we would build a destroyed model and then recreate it, so that it could be destroyed.

Getting back to your question, the set of Osaka took a couple of weeks to build. Unfortunately, because the sets were built “destroyed” first and then recreated to look complete, and because we got better and better at building these things so that they could easily destroy them, sometimes they could be destroyed inadvertently by just leaning against them. So for example, getting back to that point, the Osaka castle took twenty days to build, and it was destroyed in a moment.

DID YOU REALIZE 50 YEARS AGO WHAT YOU WERE GETTING INTO WHEN YOU WERE WORKING ON THIS FILM?

Sadamasa Arikawa: I was not listed in the credits, but I was a camera operator on this film; there were certain scenes I was involved in, such as the blowing wind [storm] sequence, that I felt were quite magnificent. I had a sense of that at the time. I had a sense that this was a great love story, of a strong man and a beautiful woman. However, along with this romance film I was involved with, there was this wonderful monster, and I was subjected to questions from my co-workers and superiors, such as, “What do you think you’re doing? Do you guys think you’re going to make any money on this?” I am a sensitive person myself, sensitive to the suggestions of others, and so the truth is I felt the same as the complaints of the people I was working with, that maybe we were not making something so great. But, I also truly felt that we were making a great film as well.

YOU WORKED AS A CAMERA OPERATOR ON GOJIRA, WHICH WAS DIRECTED BY ISHIRO HONDA, AND YOU DIRECTED SPECIAL EFFECTS FOR GODZILLA VS. THE SEA MONSTER AND SON OF GODZILLA, WHICH WERE DIRECTED BY JUN FUKUDA. WHAT WERE THEY LIKE TO WORK WITH?

Sadamasa Arikawa: When I worked with Mr. Honda, I was just beginning this career, so he was like a leader to me. But when I worked with Mr. Fuduka, we were in the same generation. We had to cooperate with each other; we also had rivalry with each other. Mr. Fukuda knew my pictures, and I knew his. When we worked together, I put a lot of attention into the special effects instead of drama. That’s how we had rivalry.

DESCRIBE THE WIRE WORK THAT IT TOOK TO GIVE TO LIFE TO THE GIMANTIS (GIANT PREYING MANTIS) AND SPIEGA (GIANT SPIDER) IN SON OF GODZILLA.

Sadamasa Arikawa: We needed twenty people, in a space about three meters square. There were thirty wires, three wires to each leg. The wires were hung from the stage. Everybody had a number, and when I called a number, everybody knew which leg to move. I’m so satisfied with how we moved the monsters. The wires were about 0.01mm wide, made by the studio wire department.

THERE WAS A LOT OF COMPOSITE WORK IN SON OF GODZILLA, TO COMBINE MONSTER AND HUMANS IN THE SAME SHOT, WHICH WAS UNUSUAL FOR FILMS OF THIS PERIOD.

Sadamasa Arikawa: The reason I used many shots with monsters and humans in one screen is because I wanted to make it, in this movie, easy to compare the sizes of monsters and humans. To make the monsters scarier, I needed shots to show the sizes of monsters and humans in one shot.

HOW WAS THE EFFECT ACHIEVED FOR THE SPIDER SPRAYING ITS WEB?

Sadamasa Arikawa: The spider web was made by rubber glue. We warmed rubber glue first, and it was sprayed out from a nozzle. It only went a certain distance, like three meters, so we only used close shots.

[AS HOST TRIES TO WRAP UP, ARIKAWA STANDS TO MAKE ONE LAST SPEECH TO THE AUDIENCE, REGARDING HIS CONTRIBUTION TO SON OF GODZILLA]

I’d like to speak. When I did this movie, I did my best. Last night, I saw people who came here [to see Gojira]. I did not do the original Godzilla, but please take care of my new Godzilla!

Copyright 2000 Steve Biodrowski