Making Your Blood Run Cold, Again.

Robert Blake has made a career out of playing realistic, believable characters, whom audiences can relate to as regular, ordinary people – whether a poor young boy in THE TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE or a streetwise cop BARETTA. In fact, in his most famous (and chilling) feature film performance, he portrayed a real person in Richard Brooks’ adaptation of Truman Capote’s non-fiction novel IN COLD BLOOD.Therefore, it is a bit of a shock to find this actor suddenly playing not a regular Joe but a surreal character who may or may not exist only in the mind of a demented protagonist. His small but pivotal supporting performance in David Lynch’s LOST HIGHWAY is one of the film’s many highlights – almost as unnerving, in its own way, as his role in IN COLD BLOOD, though with a strange overlay of dark humor. Of course, the fact that the Mystery Man (as he is billed in the credits) doesn’t exist makes him somewhat less frightening on a visceral level that a real-life psychopathic killer. But the unreal element adds its own layer – a sense of the uncanny, of dread all the more frightening because it is so unspecified and mysterious.

No one was more taken aback by this unusual bit of casting against type than Blake himself. “I was surprised David Lynch called me,” said the actor. “I would have thought that he’d call Dennis Hopper or one of his guys. But he just said, ‘Hey, I want you to play this.’ I have no idea why! I read the script like nine fuckin’ times, and I didn’t understand one fuckin’ word of it! I said, ‘Are you sure you want me to play this? I’ll be the most cooperative actor in the world, because I have no fuckin’ opinion on anything of what the hell to do!’ I made this mistake once of asking him what my character was, and I realized that he really is too much of an artist to be that specific about things. It was an extraordinary experience. He really is a rare commodity in America. In Europe and other places, you find film authors, or you find them in colleges or at Sundance, where somebody takes an 8mm, four dollars, and goes out and makes a movie. But this guy does it as a professional and really makes the whole film, everything.”

Blake found that his director was resistant to providing analytic explanations for his bizarre characters. “I don’t think he knows!” exclaimed Blake. “He doesn’t come from that place at all. As a matter of fact, when you work with him you have to be really ready to come to him as a child. You work with Sidney Pollack or Mark Rydell, and they want the spine of the character and the subtext, the conflict, the psycho-neurotic mumbo-jumbo, and all of that. David Lynch doesn’t – and I understand it now, because I found out that he was a painter, an artist. He really speaks an entirely different language. He’s very creative, but he doesn’t speak the normal cinema language. If you don’t like him and trust him and get up off of your own shit, it can be a disaster, because he’ll do things: You never find Martin Scorsese or Sidney Pollack walking up to you and saying, “Okay, turn and look at me. Now tell me how you’re going to say the line.’ And I start to turn to the actor I’m working with, and Lynch says, ‘No, no, no! Look at me! Say it to me.’ Directors don’t do that. They let you work off the other actor. He’d see me walking to my dressing room and say, ‘Robert, how are you going to say that line?’ And you just have to go there with him, or it will be a fucking nightmare.”

Blake added that this approach was totally the opposite of what one learns in acting classes, about “working off the other artists, taking it from them. You never give an actor a line reading. You don’t tell him to scratch his nose when he says this word. But David is like that, and you have to be loose enough and trusting enough of yourself to say, ‘You know, I don’t need all that other shit. I don’t need that Method. I can do this. I can do this just the way a child could.’ So then you’re okay. Otherwise, he’ll throw you all day long, because he doesn’t do anything that directors, as such, do.”

Blake refers to this process simply as “letting go.” He was able to find a basis for this trust in his own early career, as a child actor. “I come from the 1930s, 1940s,” he recalled. “I grew up at MGM, and I worked with Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, all those people. And I went to Warner Brothers, as a child, worked with Bogart, [John] Huston, and those people. Tracy said, ‘The two most important things in acting are a child’s imagination and a sense of truth.’ That’s what you have to bring to David. You have to get rid of all that acting technique, the classes, the books, and all that bullshit, and just bring him a child’s imagination and a sense of truth, so that you can make true whatever it is that he wants you to do.”

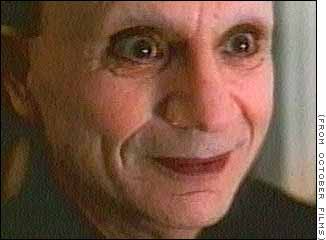

Blake found that verbal communication often didn’t work with his director, who preferred visual modes. For example: “I said, ‘David, I have some ideas about how this character should look.’ He said, ‘No, no, no! Just show me. Use your imagination.’ And I said, ‘Oh, yeah. That’s what Tracy said.’ I went off with the makeup people, and I got into this whole weird, fuckin’ Kabuki-looking guy with ears [sticking out] and stuff. I was imagining in my own strange world those times I have seen things that weren’t there, when a ghostly appearance occurred. I knew it was my imagination; I wasn’t really seeing something. But I sort of knew what the Devil looked like; I knew what Fate looked like. I used to have this image of myself that would come to me sometimes. I’d go out to the desert and get involved in some strange, isolated kind of thing, and all of a sudden I would come to myself as this white, ghostly creature. I said, ‘Oh yeah, that’s my conscience talking to me.’ So I started going with that. I cut my fuckin’ hair off, and I put a crack in the middle of it and all this shit. And the makeup people said, ‘You’re going crazy, man! Nobody in this movie looks like that; everybody looks regular!’ I said, ‘Leave me alone; just give me some shit.’ I put this black outfit on. I walked up to David, and he said, ‘Wonderful!’ and turned around and walked away. Now, you could never do that with a regular director, take a film where there’s all these people who look absolutely normal and say, ‘I’m going to go completely away and make an entirely different film. My film will be separate from Pullman’s, Arquette’s or anybody else’s. I’m making a surrealistic, oriental film!’” – he laughs – “And I did! Imagine how strange his thinking must be to look at me looking all weird like that and [with] all these other straight-looking people, and say, ‘Oh, yes. That’ll work’ You’d never even think of doing that with Sidney Pollack. You wouldn’t walk on his set like a Kabuki dancer. But Lynch just said, ‘Use your imagination. How do you see this guy? What the hell is he?’ Because I asked him what the guy was, and he didn’t answer me!”

Blake added that Lynch “immediately led me to believe that he didn’t deal in those terms, any more than you would walk up to Salvador Dali or Chagall and say, ‘What do you mean in this painting.’ ‘What the fuck do you mean by “What do I mean”? I painted the painting: you get what you get out of it; I got what I got out of it.’ I’m really convinced that Lynch is that way. You know better than to do that with a painter. Nobody goes up to a painter, especially an abstract painter – you don’t ask Heronimous Bosch, ‘What the fuck is that?’ Because he would simply say, ‘If you don’t get it, I can’t tell you. If it don’t mean nothing to you, get the fuck out of here!’ You can’t go up to a great musician who’s just finished an abstract impression of what the tune was and say, ‘Now, what were you doing?’ ‘I was doing my thing.’ David just does his thing.”

Blake’s Mystery Man (as he is called in the credits) is the first intrusion of the preternatural into what has up until that point been a fairly concrete, if somewhat mysterious, narrative. The question then was: how would the normal world react to this portentous, corporeal apparition? “The character does some surreal things,” said Blake, “but I was very curious as to what David was going to do with the way I looked, how was he going to have people react? Normally, when you see somebody who looks that way, you say, ‘God you look weird, man! What the fuck is your story?’ I thought, ‘What is David going to do when I walk into this party scene?’ And it’s very interesting, because he told everybody, ‘React to him like he’s a butler. Don’t look at him and say, “Boy, is he weird!”’ He made all of them behave as though I looked normal. That was just a choice he made at the spur of the moment. I didn’t have Bill Pullman go, ‘Hey, you look crazy!’ He just turned around and said, ‘Hi, how are ya?’ David didn’t have anybody refer to the way I looked throughout the whole movie. No one was surprised or repulsed. He just said, ‘That’s what I’m going to do with this character: I’m going to have everybody deal with him like he looks normal.’ And I never asked him why he did that, but I probably wouldn’t have it I was directing. I would have had people ‘behave’ around that makeup, but he didn’t do that.”

Of the final result, Blake said, “I saw the film, and I liked it the way I like Ingmar Bergman, but I didn’t understand it. What you enjoy is the experience of seeing it. I remember when I was a young man; we always used to go to Bergman films, WILD STRAWBERRIES and all these strange films. Everybody would come out, sit there till three o-clock in the morning, smoking dope and discussing the movies. I would, too, except I knew I was full of shit!” – he laughs – “‘Well, I really think that when Max Von Sydow was doing this, he was really doing that.’ It was bullshit. It’s the same with David. I don’t understand it; you just have to groove with it. He takes a realistic character like Robert Loggia’s character and all of a sudden he stops a guy on the highway and beats the shit out of him for following him too close. Where the fuck did that come from, and where did it go to? You just have to roll with it. Like I said, if I was looking at Heronymous Bosch and finding one corner of the painting and saying, ‘Well, if there’s a squirrel over there fucking a cockroach, I wonder what that means?”

Although working with Lynch was a different experience for Blake, it is one that he would not mind repeating. “I would like to work with him sometime where I have a chance to act,” he said, “When you’re doing something so obtuse and stylized like that, I think, personally, the best thing is not to go with it: you let the makeup, wardrobe, character, and the dialogue speak for themselves, and as an actor, your job is almost to be the narrator. Like in the first scene, walking to Bill Pullman: the whole situation is so macabre and so menacing that the thing to do as an actor is to leave it alone. If you start going with it, then it’s going to go over the fucking top; it’s going to become a joke to the audience. So you don’t get to do much acting. If I came in to play a scene like ‘Hey, you fucked my girlfriend, so I’m going to kill you,’ I get to act that. But if I come in dressed in this Kabuki outfit and all this shit, then the best thing for me to do is nothing. I could have made a big deal out of taking the gunout of Pullman’s hand and pointing it at Loggia and killing him, but everything else was cooking, so the less you do, the better it’s going to be. Otherwise, it’ll be all over the fuckin’ place. When I came in to see Pullman, I could have had a whole lot of weird, strange shit going on, but then it would be all fucked up.”

Blake explains this approach by pointing to his early apprenticeship. “I was trained by very good actors,” he stated. “I was on the set when I was five years old with Spencer Tracy. A lot of what I learned growing up in terms of artistry is very clean, very tidy, very organized. If you look at the great films of Warner Brothers or Metro, you don’t see anything like you would see in a film like CASINO: there’s nothing loose; the dialogue is clean; you get through taking, and then I talk and look at you. What I was trained on, by Gable and all those people, was a tremendous amount of economy, simplicity. It was all like a Picasso painting. When I did TREASURE OF SIERRA MADRE and I watched Bogart work, even though he had scenes where he absolutely went insane, you didn’t see him – what we call – chewing up the scenery. He wasn’t banging off of walls and doing all this stuff; he was very clean and very specific. I like those kinds of actors. I think Anthony Hopkins has become that. The more he works, the less he does. By the time he did Hannibal Lecter, he was doing very little. He just looked – very clean, very economical. He wasn’t all over the fucking place. He wasn’t climbing the walls, wandering around. He didn’t use his arms or hands. He didn’t use any outrageous makeup. He was just clean, tidy, and fucking brilliant. Don’t give it to the audience; leave it to the audience. Which is what I was doing with the Mystery Man. Less is more, until finally was doing nothing except putting the words out.”

Copyright 1997 by Steve Biodrowski. This article originally appeared in the April 1997 issue of Cinefantastique (Volume 28, Nuber 10).

[serialposts]