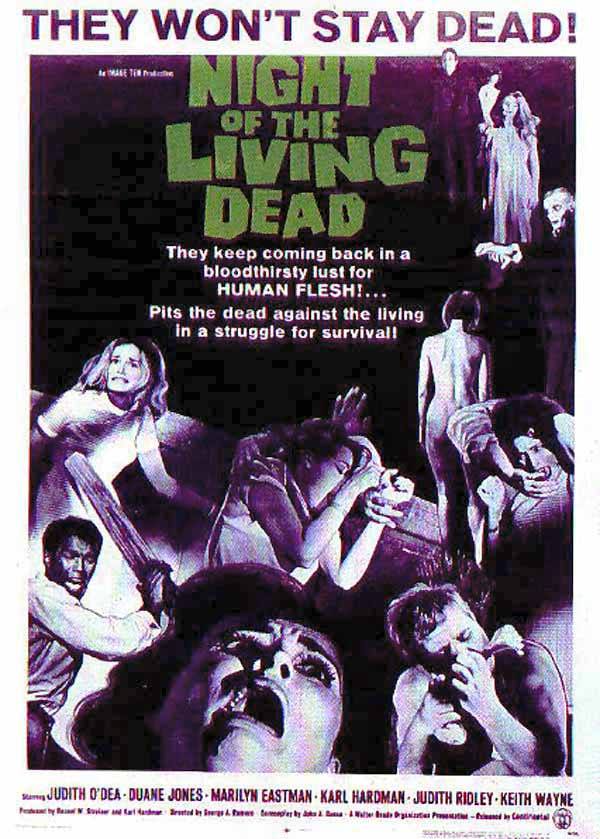

With George A. Romero’s DIARY OF THE DEAD, the latest installment in his “Living Dead” franchise, opening in exclusive engagements around the country this Friday, we offer this retrospective of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, the film that started it all.

Director-cinematographer-editor (and co-writer) George Romero set a new standard for horror with this low-budget opus, which launched a trilogy later continued with DAWN OF THE DEAD and DAY OF THE DEAD.

The limited budget actually enhances the effectiveness, as the limited locations and cast create a sense of claustrophobic dread in the face of the living dead onslaught. The symbolic impact of the home under assault from outside is immense, and the disintegration of the group within adds immeasurably to the tension. The black-and-white images convey the horror in stark detail; the camera work and editing and perfectly suited to the subject matter. It’s hard to imagine how this film could be improved on with bigger production values and/or color photography (a fact born out by the competent but uninspired remake in 1990). There’s something intense and unrelenting about this film, which deliberately violates taboos and expectations, leaving the audience with no comfort level. A cynical, downer ending perfectly caps off this long, moody masterpiece. Guaranteed to give you the creeps.

Despite sequels, remakes, and rip-offs that would seem to have run the idea into the ground, the original NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD holds up quite well today—in some ways, even better than when it was originally released. The marauding ghouls remain as frightening as ever, thanks to black-and-white photography that retains its atmospheric impact. Equally impressive, repeated viewings reveal the effectiveness of the internal conflict between the human characters, as they argue endlessly about how to face the menace, instead of coordinating their efforts to confront the common enemy. What’s interesting in retrospect is the way the film invites you into identifying with Ben because he seems to be the traditionally heroic man of action, while subtly undermining his heroic status. He’s at least as belligerent as Harry Cooper, whom we’re obviously supposed to dislike; and although we assume that Ben is taking his position because it’s the right one, it could just as easily be that he likes getting his way and doesn’t want to hear what anyone else has to say. And of course, despite all his protestations to the contrary, after all his attempts to secure the house and escape have resulted in the deaths of the other characters, Ben finally does what Harry advocated all along: he locks himself into the cellar.

RETROSPECTIVE

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD grew out of George Romero’s desire to make a commercial feature film. The young Brooklyn-born filmmaker had served his apprenticeship working in a news editing room before forming Latent Image, a Pittsburgh-based company that made industrial films. For the company’s first shot at a theatrical release, Romero and his partners opted for a horror script, taking the germ of an idea from I AM LEGEND, a modern-day vampire novel by Richard Matheson, in which a plague of the undead overwhelms human society.

“Our overriding goal was to produce something that would get enough of a release to earn back our investment and, if things went unexpectedly well, possibly even return a profit,” Romero explains. “With that in mind, we set out to make a horror flick that pushed the envelope and didn’t flinch by cutting away when things got too juicy.”

Romero’s script “grew out of a short story I had written, which was basically a rip-off of the Richard Matheson novel,” Romero recalls. “In the book and the [previous] films, the very first scene presents us with the last living human being already alone in a world of vampires. That’s Matheson’s jumping off point for what is basically a siege story. I used zombies instead of vampires; I always thought that zombies were a sort of blue collar, working class monsters that might show up in anybody’s backyard. I also felt that, rather than opening with a fait accompli, it might be more interesting to observe the world during its collapse, to watch the disintegration of the old guard as its downfall is brought about. I ripped off the siege and the central idea, which I thought was so powerful—that this particular plague involved the entire planet.”

Romero and producers Russell W. Streiner and Karl Hardman, along with seven other partners, began production with only $6,000. “Ten of us put in $600 a piece and started to shoot,” the director explains. “Gradually, we were able to raise money from investors around town. We wound up spending $70,000 in cash and owing $44,0000 in deferments, but we paid that off.”

Despite the low budget, Romero managed to get an impressive amount of camera coverage: the film is filled with interesting wide-angle setups, and the action scenes feature very effective editing of numerous angles that convey the sense of being overwhelmed by the marauding ghouls. Romero credits this to the single, old Arriflex camera he used to film the scenes and dialogue.

“When we were shooting dialogue, the camera was housed in a blimp, a gizmo designed to dampen the sound of the camera, which was as loud as a Sherman tank,” Romero jokes. “The blimp weighed as much as a human and was roughly the size of a Volkswagen. This largely explains why the dialogue sequences are so static. When the camera was out of the blimp, it was a twelve-pound wonder. It could be held one-handed, with your thumb on a red ‘Shoot’ button—only slightly more cumbersome than today’s camcorders. The only thing about it was the film load, but you didn’t have to load 440-foot reels; you could load 100-footers and feel as free as the breeze. I was able to shoot only MOS [without sound] sequences handheld; that’s why they look like newsreels. I was able to shoot non-dialogue action sequences the same way; that’s why I was able to make so many shots. I always used to say that I’d rather have 100 bad shots than ten that are beautiful. You can edit 100 shots in a million different configurations, until you come up with something that’s close to what you intended. A single shot, no matter how perfect, leaves you no options.”

The result is a film that conveys the immediacy of a documentary newsreel. “In those days, the news came to us in black-and-white,” Romero recalls. “Our images look like newsreel images mainly because they were pretty much unlit. We were working with a package of 650- and 1000-watt lights—no soft lights, no scrims. I did what I could trying to make the starkness seem deliberate, stealing what I could remember from Welles’ OTHELLO and MACBETH. Only backhanded credit, if any, is deserved—the sort of credit awarded to a cat burglar. The images that most resemble reality were shot in daylight—most notably, the scenes of a posse arriving with their dogs to scour the countryside.”

Looking back on his successful efforts to squeeze quality out of limited resources, Romero seems to consider himself unworthy of the praise that his debut film has earned.” “NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD was born of backhanded strokes, made speedily and in most cases out of desperation,” he states. “When I made the film, I wasn’t an auteur in command; I was a student, an apprentice, learning every day. I had read my share of Poe. I collected EC Comics, and I’m old enough to have seen FRANKENSTEIN [1931] and DRACULA [1931] on the big screen—when they were re-released. I saw THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD [1951] in its first run, also on the big screen. I was a fan but not a scholar. I had a gut feeling for what worked and what didn’t work. I stole what worked, for me, and used it, in some cases shot for shot, wherever I could.”

As for the artistic level—and it’s hard not to see some kind of message in the film—Romero states, “We weren’t actually trying to use NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD as a forum for our socio-political leanings. They simply crept in through the back door. Perhaps there is some back-handed credit due for not shrinking from our views, for letting them show.”

VIDEO & DVD DETAILS

The public domain status of the original NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD has led to numerous atrocities perpetrated on what should be treated as a classic of horror cinema. There was a computer-colorized version released on video. There is supposed to be an edited cut in circulation, although this is probably only a myth. But perhaps the greatest atrocity was perpetrated by John Russo himself, who released a so-called “30th Anniversary Edition” on video and DVD in 1999. This version deletes 15 minutes of the original and adds news scenes and an original score.

The preferred disc is Elite Entertainment’s “Millennium Edition” DVD; in fact, its images are clearer and sharper than the theatrical prints were when the film was originally released, so the film’s impact is that much greater. Released in 2002, is the disc contains two informative audio commentaries from the director, cast, and crew, which were available on their previous 1997 DVD, and adds several more extras, including an interview with the late Duane Jones. And you don’t want to miss the short spoof “Night of the Living Bread”!

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968). Directed by George Romero. Written by John Russo and George Romero. Cast: Duane Jones, Judith O’Dea, Karl Hardman, Marilyn Eastman, Keith Wayne, Judith Ridley, Kyra Schon.

[serialposts]