Our nearest neighbor in the Solar System, the Moon has long inspired the imagination of humanity. Everyone has heard of “the Man in the Moon.” In ancient cultures, lunar eclipses were feared as portents of disaster. The phases of the Moon were thought to have astrological significance, influencing the behavior of people on Earth – a belief that persists to this day (hence the word “lunatic,” derived from “lunar”). In 1935, the Great Moon Hoax convinced many people that life had been discovered on the lunar surface, at around the time that astronomers were establishing that the Moon contained no water or atmosphere – the essentials for life.

Today, the attraction of the Moon still pulls on in our hearts and minds, as evidenced by the literally hundreds of movies that use the word in their titles, usually for romantic and/or poetic purposes (e.g., Mizoguchi’s masterpiece UGETSU MONOGATARI, which translates as “Tales of Moonlight and Rain”). However, thanks to the Apollo landing, every school child knows that the Moon is a barren wasteland, uninhabited by aliens; this undermines some of its potential for science fiction adventure stories (after all, if the place is not the abode of Moon Men intent on destroying the Earth, what good is it?). When it comes to cinefantastique, use of th word “moon” in the title is more likely to represent an excursion into lycanthropy (FULL MOON HIGH, MOON OF THE WOLF, etc) than a journey to outer space. Yet science fiction filmmakers still continue to find occasional use for the orbiting satellite, most recently in MOON, which opens this weekend.

What follows is a look at some of the more memorable examples of Moon-based movies…

Moon movies really kick off with A TRIP TO THE MOON, George Melies short and whimsical 1902 film. The story combines elements of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells: as in Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, the astronauts ride in a space ship shot out of a canon; as in Wells’ First Men in the Moon, the Earth explorers discover crustacean-like Moon Men. But if Melies owes his humorous tone to anyone at all, it is to Edgar Allan Poe for his satirical hoax “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” which describes a trip to the moon in a hot-air balloon. Fantasy rather than science fiction, Melies’ film has a group of men in business – rather than space – suits landing on the lunar surface, where they breathe without trouble about the lack of atmosphere; their umbrellas take root when stuck in the ground; and the annoying moon men go up in a puff of smoke when struck. The primitive quality of A TRIP TO THE MOON date it somewhat (Melies films all scenes in master shots, never cutting to different angles), but the film retains its charm over a century later.

In 1929, the great Fritz Lang gave us WOMAN IN THE MOON, which is probably the first feature film to deal with the subject of lunar travel in a serious manner. The lengthy story (the restored version of the film runs over two hours) involves the rivalry during a mission that takes place following the discovery that large quantities of gold exists on the moon. Unfortunately, the silent film was drowned out by the clamor of the new sound era of film-making. Although neglected, at least one writer believes WOMAN IN THE MOON is “quite an amazing film” that “shows Lang at the height of his powers.”

In 1929, the great Fritz Lang gave us WOMAN IN THE MOON, which is probably the first feature film to deal with the subject of lunar travel in a serious manner. The lengthy story (the restored version of the film runs over two hours) involves the rivalry during a mission that takes place following the discovery that large quantities of gold exists on the moon. Unfortunately, the silent film was drowned out by the clamor of the new sound era of film-making. Although neglected, at least one writer believes WOMAN IN THE MOON is “quite an amazing film” that “shows Lang at the height of his powers.”

With Lang’s WOMEN IN THE MOON overlooked, the first film that earned recognition for offering a believable portrait of space travel is George Pal’s 1950 production of Robert Heinlein’s novel, DESTINATION MOON. A meticulous piece of work that stuck closely to the known science of its day, DESTINATION MOON is a landmark in terms of special effects and production design (including a wonderful panoramic painting of the lunar scenery by noted astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell); it is also, unfortunately, slightly dull. Without a threat of menacing aliens, the moon is not necessarily very interesting, so the film lacks drama, coming across a bit like a psuedo-documentary. Still, you have to give the film credit for the integrity of sticking to reality instead of drifting off into fantasy.

With Lang’s WOMEN IN THE MOON overlooked, the first film that earned recognition for offering a believable portrait of space travel is George Pal’s 1950 production of Robert Heinlein’s novel, DESTINATION MOON. A meticulous piece of work that stuck closely to the known science of its day, DESTINATION MOON is a landmark in terms of special effects and production design (including a wonderful panoramic painting of the lunar scenery by noted astronomical artist Chesley Bonestell); it is also, unfortunately, slightly dull. Without a threat of menacing aliens, the moon is not necessarily very interesting, so the film lacks drama, coming across a bit like a psuedo-documentary. Still, you have to give the film credit for the integrity of sticking to reality instead of drifting off into fantasy.

DESTINATION MOON was followed up by 1953’s less well-remembered PROJECT MOON BASE, which was also scripted by Heinlein. Meanwhile, the low-budget ROCKETSHIP X-M(1950) just missed the Moon: its rocket ship (containing Lloyd Bridges, among others) veers off course and lands on Mars instead – quite an impressive accomplishment. Also in 1953 was the immortal camp classic CAT-WOMEN OF THE MOON, which is more or less summed up in its title – what more could you possibly need to know?

In 1958, Hollywood stars Joseph Cotten and George Sanders went FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON. This competent but mostly forgotten film version of the Jules Verne novel suffered a bit from the passage of time between the source material and the adaptation. Verne often made uncanny predictions about the possibilities of air travel and space flight (From the Earth to the Moon predicts that America is the country with the ambition and ability to reach the moon, and based on the fact that the rotation of the Earth would provide an extra boost to any rocket launch, Verne picks Texas and Florida as the likely launching sites.) However, the method of travel – shooting a space ship out of a canon – would instantly kill any astronauts on board.

In 1958, Hollywood stars Joseph Cotten and George Sanders went FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON. This competent but mostly forgotten film version of the Jules Verne novel suffered a bit from the passage of time between the source material and the adaptation. Verne often made uncanny predictions about the possibilities of air travel and space flight (From the Earth to the Moon predicts that America is the country with the ambition and ability to reach the moon, and based on the fact that the rotation of the Earth would provide an extra boost to any rocket launch, Verne picks Texas and Florida as the likely launching sites.) However, the method of travel – shooting a space ship out of a canon – would instantly kill any astronauts on board.

The same year as FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON, Hollywood gave us MISSILE TO THE MOON, about a pair of escaped convicts who are forced by a scientist to pilot the titular ship – the plot twist being that the scientist is actually a moon-man who wants to get back home.

1963 gave us THE MOUSE ON THE MOON, a political satire directed by Richard Lester (who would go on to direct A HARD DAY’S NIGHT). This sequel to THE MOUSE THAT ROARED (in which a tiny country named Grand Fenwick declares war on the U.S. in the hope of being rebuilt with American dollars after being defeated) depicts what happens when Grand Fenwick decides to enter the space race: Not only do they win; they end up rescuing the astroanut teams from the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. The film suffers a bit from the absence of Peter Sellers (who played multiple roles in ROARED), but Ron Moody, Margaret Rutherford, and Terry-Thomas do a good job of filling his shoes. The New York Times’ film critic Bosley Crowther called the result “a blithely outrageous spoof” full of “daffy situations and some very droll dialogue.”

1963 gave us THE MOUSE ON THE MOON, a political satire directed by Richard Lester (who would go on to direct A HARD DAY’S NIGHT). This sequel to THE MOUSE THAT ROARED (in which a tiny country named Grand Fenwick declares war on the U.S. in the hope of being rebuilt with American dollars after being defeated) depicts what happens when Grand Fenwick decides to enter the space race: Not only do they win; they end up rescuing the astroanut teams from the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. The film suffers a bit from the absence of Peter Sellers (who played multiple roles in ROARED), but Ron Moody, Margaret Rutherford, and Terry-Thomas do a good job of filling his shoes. The New York Times’ film critic Bosley Crowther called the result “a blithely outrageous spoof” full of “daffy situations and some very droll dialogue.”

Hercules battled the Moon Men in 1964’s Italian import HERCULES AGAINST THE MOON MEN. Also that year, Charles Schneer produced FIRST MEN IN THE MOON, an adaptation of the novel by H. G. Wells. The film is basically a showcase for Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion special effects; nevertheless, it retains the Victorian setting and even some of Wells’ ideas, thanks to a script co-written by genre expert Nigel Kneale (best known for his Quatermass serials on British television). With NASA’s real-life Apollo missions only five years away from actually reaching the moon, the film updates much of the science (eliminating the flora on the lunar surface and giving the astronauts space suits made from deep sea-diving equipment), and the story is bracketed by scenes set in contemporary times to help make the period story more palatable to a modern audience (a technique later used in Titanic). Still, for all its virtues, the film feels a bit slow and episodic. Fortunately, Harryhausen’s work is splendid as always, and Lionel Jeffries is quite an amusing incarnation of Wells’ absent-mind professor, Cavor.

Hercules battled the Moon Men in 1964’s Italian import HERCULES AGAINST THE MOON MEN. Also that year, Charles Schneer produced FIRST MEN IN THE MOON, an adaptation of the novel by H. G. Wells. The film is basically a showcase for Ray Harryhausen’s stop-motion special effects; nevertheless, it retains the Victorian setting and even some of Wells’ ideas, thanks to a script co-written by genre expert Nigel Kneale (best known for his Quatermass serials on British television). With NASA’s real-life Apollo missions only five years away from actually reaching the moon, the film updates much of the science (eliminating the flora on the lunar surface and giving the astronauts space suits made from deep sea-diving equipment), and the story is bracketed by scenes set in contemporary times to help make the period story more palatable to a modern audience (a technique later used in Titanic). Still, for all its virtues, the film feels a bit slow and episodic. Fortunately, Harryhausen’s work is splendid as always, and Lionel Jeffries is quite an amusing incarnation of Wells’ absent-mind professor, Cavor.

If 1967’s ROCKET TO THE MOON feels a bit like FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON, the reason is that both films were inspired by the writings of Jules Verne. This time we get stars Burl Ives and Troy Donahue instead of Joseph Cotten and George Sanders, in a story about real-life P.T. Barnum financing a trip to the Moon. Terry-Thomas (of THE MOUSE ON THE MOON) and Lionel Jeffries (of FIRST MEN IN THE MOON) lend their support to the proceedings. This independent production from euro-sleaze merchant Harry Alan Towers (also known as THOSE FANTASTIC FLYING FOOLS) was meant to rival lavish productions like THOSE MANGIFICENT MEN IN THEIR FLYING MACHINES. DVD Talk’s John Stuart Galbraith opines that the film is “shamelessly derivative but entertaining,” adding that it “wears thin during its aimless middle section, but has enough amusing ideas and performances to sustain it through to the end.”

If 1967’s ROCKET TO THE MOON feels a bit like FROM THE EARTH TO THE MOON, the reason is that both films were inspired by the writings of Jules Verne. This time we get stars Burl Ives and Troy Donahue instead of Joseph Cotten and George Sanders, in a story about real-life P.T. Barnum financing a trip to the Moon. Terry-Thomas (of THE MOUSE ON THE MOON) and Lionel Jeffries (of FIRST MEN IN THE MOON) lend their support to the proceedings. This independent production from euro-sleaze merchant Harry Alan Towers (also known as THOSE FANTASTIC FLYING FOOLS) was meant to rival lavish productions like THOSE MANGIFICENT MEN IN THEIR FLYING MACHINES. DVD Talk’s John Stuart Galbraith opines that the film is “shamelessly derivative but entertaining,” adding that it “wears thin during its aimless middle section, but has enough amusing ideas and performances to sustain it through to the end.”

One year later, Stanley Kubrick gave us 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY. Although only the film’s second section deals with the moon, this has to be considered the greatest “moon movie” ever made, thanks to the utterly convincing special effects and the beautiful classical music used to lend a balletic sense of beauty to space travel. Not only do we get a trip to the moon; we also get a tour of the lunar surface, where TMA-1 (Tycho Magnetic Anomaly) has been discovered – a strange monolith buried beneath the Earth’s surface, presumably for humanity to discover when they have achieved the first step in space travel. The film’s depiction of space travel still ranks as the best and most scientifically accurate ever seen on screen.

One year later, Stanley Kubrick gave us 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY. Although only the film’s second section deals with the moon, this has to be considered the greatest “moon movie” ever made, thanks to the utterly convincing special effects and the beautiful classical music used to lend a balletic sense of beauty to space travel. Not only do we get a trip to the moon; we also get a tour of the lunar surface, where TMA-1 (Tycho Magnetic Anomaly) has been discovered – a strange monolith buried beneath the Earth’s surface, presumably for humanity to discover when they have achieved the first step in space travel. The film’s depiction of space travel still ranks as the best and most scientifically accurate ever seen on screen.

As if to offer a contrast between science-fiction-based-on-fact and science-fiction-as-all-out-fantasy, 1968 also offered us DESTORY ALL MONSTERS, in which Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra fight off an alien race from the Moon. The depiction of space travel is the stellar opposite of Kubrick’s – completely unbelievable but completely exciting, in a boy’s adventure kind of way; if you ever dreamed of being an astronaut flying through space and defending the Earth from aliens, this is probably exactly how you imagined it. Unfortunately, the real lunar landing eclipsed this type of adventure-fantasy, and “Moon Movies” – unable to compete with reality – began fading from the screen.

As if to offer a contrast between science-fiction-based-on-fact and science-fiction-as-all-out-fantasy, 1968 also offered us DESTORY ALL MONSTERS, in which Godzilla, Rodan and Mothra fight off an alien race from the Moon. The depiction of space travel is the stellar opposite of Kubrick’s – completely unbelievable but completely exciting, in a boy’s adventure kind of way; if you ever dreamed of being an astronaut flying through space and defending the Earth from aliens, this is probably exactly how you imagined it. Unfortunately, the real lunar landing eclipsed this type of adventure-fantasy, and “Moon Movies” – unable to compete with reality – began fading from the screen.

In 1969, Hammer Films, a company usually associated with horror movies, tried their hands at science fiction with MOON ZERO TWO. Despite opening credits music that deliberately evokes SPACE ODYSSEY, the film is actually more of a melodrama involving a salvage expert on the moon who gets mixed up with some criminals who hijack a mineral-rich asteroid and crash it onto the lunar surface.

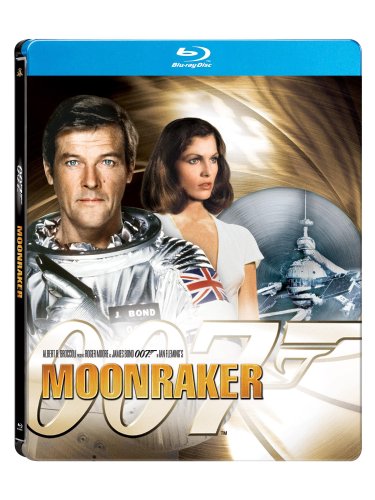

Ten years later, MOONRAKER never reached the lunar surface. Instead, James Bond battled bad guys on an orbiting space station. Although the film is pretty much a self-spoof, filled with laser beams and tongue-in-cheek action-adventure, the outer space special effects are pretty stellar, with an eye for as much accuracy as possible.

Another film that tried eat its cake and have it too was SUPERMAN II.Though mostly Earthbound, the film featured an early sequence of escaped super villains murdering astronauts on the surface of the Moon. The comic book nature of the material gave the filmmakers license to ignore reality in order to suit the needs of creating an exciting sequence that would not be filmed with total realism, but the production design and special effects are clearly influenced by the real-life lunar landings, with recognizable space suits and a lunar rover.

Another film that tried eat its cake and have it too was SUPERMAN II.Though mostly Earthbound, the film featured an early sequence of escaped super villains murdering astronauts on the surface of the Moon. The comic book nature of the material gave the filmmakers license to ignore reality in order to suit the needs of creating an exciting sequence that would not be filmed with total realism, but the production design and special effects are clearly influenced by the real-life lunar landings, with recognizable space suits and a lunar rover.

AMAZON WOMEN OF THE MOON (1987) is an anthology of comedy sketches, along the lines of THE GROOVE TUBE, TUNNEL VISION, and KENTUCKY FRIED MOVIE. The film takes its title from one of the longer episodes, a spoof of bad sci-fi flicks like CAT-WOMEN OF THE MOON. Stern-faced actor Steve Forrest sends up his tough-guy looks as the leader of the mission, and Sybil Danning makes an attractive Queen of the Moon.

A GRAND DAY OUT (1994) is one of the few “Moon Movies” (besides SPACE ODYSSEY) to earn an Academy Award nomination. The stop-motion film, written and directed by Nick Park, was nominated in the animated short category but lost to Park’s other film, CREATURE COMFORTS. GRAND DAY OUT introduced the world to the delightful duo of Wallace and Gromit, a somewhat dense human and his considerably sharper canine companion. In their debut, Wallace runs out of cheese and gets the bright idea that he can find a ready supply on the Moon; being an inventor, he whips up a rocket ship in his basement, and off they go. Unfortunately, the lunar surface is not as palatable as they hoped, and they encounter a somewhat threatening robot, but everything works out well in the end. The film’s linear storyline is primitive compared to later Wallace and Gromit films, but the humor and charm make this fanciful excursion a wonderful fantasy in the tradition of Melies A TRIP TO THE MOON.

A GRAND DAY OUT (1994) is one of the few “Moon Movies” (besides SPACE ODYSSEY) to earn an Academy Award nomination. The stop-motion film, written and directed by Nick Park, was nominated in the animated short category but lost to Park’s other film, CREATURE COMFORTS. GRAND DAY OUT introduced the world to the delightful duo of Wallace and Gromit, a somewhat dense human and his considerably sharper canine companion. In their debut, Wallace runs out of cheese and gets the bright idea that he can find a ready supply on the Moon; being an inventor, he whips up a rocket ship in his basement, and off they go. Unfortunately, the lunar surface is not as palatable as they hoped, and they encounter a somewhat threatening robot, but everything works out well in the end. The film’s linear storyline is primitive compared to later Wallace and Gromit films, but the humor and charm make this fanciful excursion a wonderful fantasy in the tradition of Melies A TRIP TO THE MOON.

With the Moon no longer quite so mysterious as it once was, the number of films that focus their attention on the lunar surface has dwindled. Earth’s lone satellite is only humanity’s first step into outer space, and filmmakers who seeking space invaders, alien cultures, and strange new worlds must look further out into space. When science fiction franchises like STARK TREK imagine a future when travel to the far reaches of the galaxy is possible, the Moon starts to lose its lustre.

That may be changing, thanks to the passage of time since Neil Armstrong made the giant leap for mankind onto the lunar surface. For those too young to have been impressionable children during that era, the lunar landing may seem less like a piece of history and more like an incredible legend. As Duncan Jones, director of MOON, said in a Q&A posted here:

The thing about the Moon is that I was born after the Apollo missions went to the moon. For a lot of our generation, it’s something very mysterious and slightly unbelievable. Even if you know that humanity has been to the moon, it feels a bit mythic and legendary; it doesn’t feel like something we can relate to. The fact that all of us can look up and see the moon at night…it’s like this place that none of us gets to visit. So I think there’s a mystery there. Even if we know everything about it from a scientific basis, there’s still something so mysterious about it. It’s the obvious place to set science fiction because it’s the first step….

[serialposts]