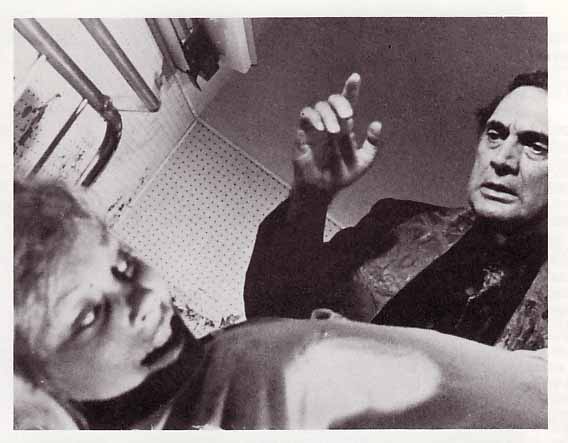

BEYOND THE DOOR II (titled SHOCK in its native Italy) is the last directorial effort from cult figure Mario Bava, the cinematographer-turned-director who created such horror classics as BLACK SUNDAY (1960) and BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1965). Unfortunately, this is a weak swan song, a coda that reprises motifs from his earlier operas, but without the bravura brio that elevated those works to the level of macabre art. The film is not without interest to fans with patience to sit through the dull recitatives in exchange for the occasional beautiful aria, but the pleasures are few and far between: the anticipation elicited by the patented slow tracking shots that seem to draw the viewer into the movie; the uneasy shudder as the statue of a hand, propelled by an unseen force, slides along a display case and crashes to the floor; the delirious vertigo of an anti-gravity shot – a prostrate woman’s hair floating up into the hair -that perfectly conveys the mind-spinning rapture of an erotically-charged encounter with her dead lover. Continue reading “Beyond the Door II (1977) – Horror Film Review”

BEYOND THE DOOR II (titled SHOCK in its native Italy) is the last directorial effort from cult figure Mario Bava, the cinematographer-turned-director who created such horror classics as BLACK SUNDAY (1960) and BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1965). Unfortunately, this is a weak swan song, a coda that reprises motifs from his earlier operas, but without the bravura brio that elevated those works to the level of macabre art. The film is not without interest to fans with patience to sit through the dull recitatives in exchange for the occasional beautiful aria, but the pleasures are few and far between: the anticipation elicited by the patented slow tracking shots that seem to draw the viewer into the movie; the uneasy shudder as the statue of a hand, propelled by an unseen force, slides along a display case and crashes to the floor; the delirious vertigo of an anti-gravity shot – a prostrate woman’s hair floating up into the hair -that perfectly conveys the mind-spinning rapture of an erotically-charged encounter with her dead lover. Continue reading “Beyond the Door II (1977) – Horror Film Review”

Tag: Mario Bava

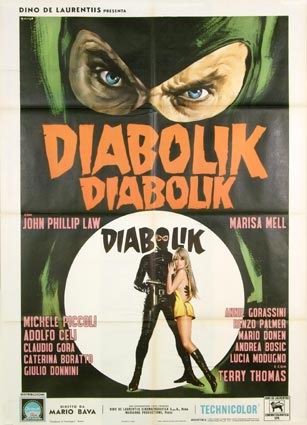

Danger: Diabolik (1968) – DVD Review

DANGER: DIABOLIK is one of the best films from the late Italian director Mario Bava. Although Bava was best known for his work in the horror genre (traditional Gothic exercises like BLACK SUNDAY, contemporary thrillers like BLOOD AND BLACK LACE ), he also directed many other types of films, including this slightly campy James Bond-style thriller with science fiction overtones. Like Gary Grant in TO CATCH A THIEF, John Phillip Law (THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD) cuts a striking and charismatic figure as the titular character, a master thief who always manages to outwit the law, in the form of Inspector Ginko (Michel Piccoli, who earns our sympathy if only because he tries so hard and fails so often). In the tradition of master criminals from Fantomas to Dr. Phibes, Diabolik uses a variety of high-tech gadgets and low-tech cunning to pull off his heists: in one amusing moment, he takes a Polaroid photograph of a room and props it up in front of the security camera, so that the guards watching the monitor see only the image of the empty room while Diabolik is ransacking the place.

DANGER: DIABOLIK is one of the best films from the late Italian director Mario Bava. Although Bava was best known for his work in the horror genre (traditional Gothic exercises like BLACK SUNDAY, contemporary thrillers like BLOOD AND BLACK LACE ), he also directed many other types of films, including this slightly campy James Bond-style thriller with science fiction overtones. Like Gary Grant in TO CATCH A THIEF, John Phillip Law (THE GOLDEN VOYAGE OF SINBAD) cuts a striking and charismatic figure as the titular character, a master thief who always manages to outwit the law, in the form of Inspector Ginko (Michel Piccoli, who earns our sympathy if only because he tries so hard and fails so often). In the tradition of master criminals from Fantomas to Dr. Phibes, Diabolik uses a variety of high-tech gadgets and low-tech cunning to pull off his heists: in one amusing moment, he takes a Polaroid photograph of a room and props it up in front of the security camera, so that the guards watching the monitor see only the image of the empty room while Diabolik is ransacking the place.

Of course, we’re supposed to root for Diabolik because he’s good-looking and cool, also because he has a passionate relationship with his girlfriend, Eva Kant (Marisa Mell), and it’s clear that the robberies are done not for the money but for the excitement and titillation. (In one of the most memorable sequences, the police wonder what he is doing with all the stolen loot, and the film cuts to Diabolik and his lady love on a huge circular bed, buried in thousands of dollars of cash as they make love.)

Produced by Dino DeLaurentiis, the film is quite lavish by Bava standards, although modest compared to Hollywood productions. Bava was an expert at using available locations and old-fashioned camera tricks (he was a cinematographer before turning to directing) to create impressive-looking settings for his films. The art direction is a 1960s vision of futurism – cool, graceful, and sleek.

Unlike the source material (the comic book is reportedly much more sinister), the overall tone of the film is amusing: it is meant to be a slick adventure, a la James Bond (a fact underlined by the presence of THUNDERBALL’s Adolph Celli in the cast), but most of all it is fun – a romp that should not be taken too seriously. Among other absurdities, Diabolik heists a 20-ton block of gold the size of a minibus. (Of course, 20 tons of gold would actually be a much smaller size, due to the metal’s great density.)

Law and Mell are great in the leads. In a film like this, there is no depth to the characterizations; the style calls for a broad kind of performance, which both deliver – especially Law, who relies on exaggerated body language when his face is obscured by Diabolik’s signature mask. They also have a wonderful on-screen chemistry that makes us like the characters in spite of the criminal ways. This isn’t just James Bond-style eroticism; there really is a delirious romanticism at work that makes the movie fly with joy, instead of just sitting there and looking pretty like a gilded artifact from another generation.

It’s unfortunate that MYSTERY SCIENCE THEATER 3000, during its final season, missed the joke and tried to use this film as an object of ridicule. The film itself is already slyly nudging its audience to enjoy the over-the-top antics with a smile on their face; there was no need for the MST3K crowd to try to add their own jokes.

The film’s ending sees Diabolik at last hoist upon his own petard, but a final fadeout wink to the audience seems to promise a sequel. Alas, none was ever made.

DVD DETAILS

The DVD features an English-language Dolby Digital mono track. Bonus features include an audio commentary from John Phillip Law and Bava-expert Tim Lucas (editor of Video Watchdog); a short documentary; a teaser trailer; a theatrical trailer; and a music video.

The documentary “From Fumetti to Film” consists mostly of an interview with comic book artist Stephen R. Bissette (best known for his work on SWAMP THING), who discusses his admiration for DANGER: DIABOLIK. He denies the “camp” label that some critics applied to the film in the wake of the BATMAN television series and points out that the tone is playful, rather than mocking of the subject matter. He also rightly points out the ways in which director Mario Bava visually translated the feel of the comic book form in a way that worked on screen – to much better effect than was achieved in other comic books adaptations from the era, such as BATMAN or BARBARELLA (the later of which also featured John Phillip Law).

Adam Hauch of the Beastie Boys also shows up to discuss the group’s “Body Movin'” music video, which uses extensive clips from DANGER: DIABOLIK. Unlike Bissette, he does think DIABOLIK is “campy,” though he is quick to add “not in a bad way.”

There are also brief snippets of interviews with producer Dino DeLaurentiis, composer Ennio Morricone, and star John Phillip Law (who describes adding mascara to his eyebrows before meeting with Bava, in order to make himself look like the comic book character). Roman Coppola (son of Francis Ford) shows up to talk about how DIABOLIK influence his film CQ, which is set in the world of Italian film-making back in the 1960s.

Overall, “Fumetti to Film” is a pleasant tribute to and appreciation of DANGER: DIABOLIK, but you won’t learn much about the making of the film. Mario Bava has been dead since 1980, but his son Lamberto (who worked as an assistant on the film) is still around. It’s too bad there is no input from him, describing the behind-the-scenes story of the making of this little masterpiece. (NOTE: “fumetti” is the Italian term for comic books; the word literally means “puff of smoke.”)

The “Body Movin'” video is included as a bonus feature, so that we can see what Adam Yauch was talking about in the “Fumetti” documentary. It’s modestly amusing but not nearly as much fun as the group’s “Sabotage.” Still, there is one worthwhile insight. You can watch the video with or without audio commentary from Yauch, who points out something that neither John Phillip Law nor Tim Lucas note in the commentary for the film itself: the numerous Jaguars (the favored car of Diabolik and his girlfriend Eva) seen in a long-shot in Diabolik’s lair. This certainly explains how Diabolik manages to continue driving one of the cars – even after we have seen one dive over a cliff.

The trailers, made for the film’s American release by Paramount, are not particularly good: the “teaser” trailer is actually just a shorter version of the “theatrical” trailer; both give away too much, including the ending! It is interesting to note that the narration is read by Telly Savalas, who would later work with Bava in LISA AND THE DEVIL.

As with almost any special edition DVD, the most eagerly anticipated bonus feature is the audio commentary; unfortunately, this one is a slight disappointment. Even with both Law and Lucas offering their insights, the commentary track often runs dry, and we are left simply sitting through the film again. Law tells some interesting stories about working with Bava and with co-star Marisa Mell, and Lucas provides lots of behind-the-scenes information. But even so, the result is often frustrating, raising as many questions as are answered.

For example, we learn that producer Dino DeLaurentiis put up $3-million to make the film, of which Bava used only $400,000. DeLaurentiis was eager to use the leftover money to make a sequel, but Bava declined. He was unhappy with the experience of making an expensive movie, because he did not like the interference from his producer (who wanted to tone down the title character’s villainy in the hope of turning him into an international icon that might launch a successful franchise). That certainly explains why Bava never made a sequel, but one is left wondering why DeLaurentiis did not proceed without him. Also, Lucas tells us that there are two English-language dubs of the film, but he barely discusses the differences or even notes that the many of the voice actors assume English accents, as if the story were meant to be set in Britain (despite the fact that Diabolik is stealing dollars, not pounds).

Even so, Bava fans will find much to enjoy here. DANGER: DIABOLIK is worth owning on DVD just for the film itself. The bonus features may not be as wonderful as one might want, but they do add considerable icing to the cake.

DANGER: DIABOLIK (1968). Directed by Mario Bava. Screenplay by Bava, Adriano Baracco, Brian Degas, Tudor Gates, and Arduino Maiuri, from the comic book character by Angela & Luciana Giussani; based on the comic book by Angela & Luciana Giussani. Cast: John Phillip Law, Marisa Mell, Michel Piccoli, Adolfo Celli, Claudio Gora.

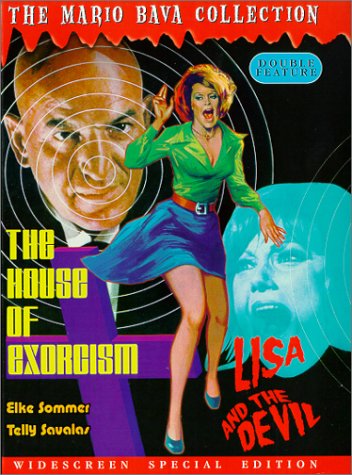

Lisa and the Devil (1973) – Horror Film Review

This is probably the last great horror film from Mario Bava (director of Gothic classic BLACK SUNDAY and the seminal giallo thriller BLOOD AND BLACK LACE) Unfortunately, LISA AND THE DEVIL, did not reach U.S. audiences in its original form for decades. When producer Alfredo Leone was unable to secure U.S. distribution in 1973, he added exorcism footage and retitled the film HOUSE OF EXORCISM. The revamped version, which is copyrighted as a separate movie, was released to U.S. theatres in 1976.

This is probably the last great horror film from Mario Bava (director of Gothic classic BLACK SUNDAY and the seminal giallo thriller BLOOD AND BLACK LACE) Unfortunately, LISA AND THE DEVIL, did not reach U.S. audiences in its original form for decades. When producer Alfredo Leone was unable to secure U.S. distribution in 1973, he added exorcism footage and retitled the film HOUSE OF EXORCISM. The revamped version, which is copyrighted as a separate movie, was released to U.S. theatres in 1976.

LISA AND THE DEVIL tell of a tourist (played by Elke Sommer) who loses her way in Italy and winds up at an isolated house filled with eccentric people, where strange things are going on. As the dream-like story develops, we get hints that there is an unseen presence lurking in the house, something to do with a tragedy that occurred years ago, involving the death of a young woman. Flashbacks suggest that Sommer’s character may be a reincarnation of the deceased lady, but there are other interpretations as well. Telly Savalas plays a butler who works behind the scenes, arranging mannequins who bear a striking resemblance to the various characters in the house. Could he be the Devil of the title, and is he manipulating everything as some kind of shadow-play for the benefit (if that is the word) of Lisa?

There are few clear answers, but that is all part of the fun with this film, which presents its narrative with a glorious stylistic verse that forces you to sit back and enjoy it, whether or not it make sense. Rather than sloppy writing, the film seems to b a deliberate attempt on Bava’s part to craft an art-house movie in horror film drag. A director who worked in a film industry that demanded commercialization and popular genres (horror, science-fiction, thrillers), Bava here is offering something closer to Ingmar Bergman (think HOUR OF THE WOLF) but with more color and exuberance than Bergman ever mustered.

Despite the higher aspirations, Bava proves that he remains a master at delivering the visceral thrills, sometimes with the most simply of techniques. There are a handful of brutal murders, along with some touches of black comedy (mostly courtesy of Savalas, who seems to be improvising some of his lines), and there is one absolutely uncanny moment guaranteed to chill your spine: As Lisa joins the guests around the dinner table, there are words of concern regarding someone else who make be lurking in the house. The sound of a crash from upstairs jerks everyone’s attention up form the table, and as if following the directions of their thoughts, the camera cuts to an attick room. As slow footfalls drop on the flooboards like approaching death, the camera winds its way through the room, apparently replicating the point-of-view of someone – we don’t know who – find his way. The moment is impossible to describe in words that equal the visuals; there is something about the pacing of the camera movment, combined with the sound effects, that creeps into your spine like icy skeletal fingers.

In a very loose kind of way, LISA AND THE DEVIL replicates some elements of CASTLE OF TERROR (a.k.a. CASTLE OF BLOOD), starring Barbara Steele. That film is an entertaining but somewhat more conventional genre piece. Bava’s movie may be less satisfying to the casual viewer, but it is an altogether more grand and impressive piece of work.

HOUSE OF EXORCISM

EDITOR’S NOTE: In the Fall 1976 issue of Cinefantastique (5:2), publisher-editor Frederick S. Clarke wrote a brief capsule comment about HOUSE OF EXORCISM in the magazine’s Film Ratings section. We include it here to provide a glimpse into how the film was seen during its initial release, before U.S. audiences knew that Bava’s LISA AND THE DEVIL had been radically altered by its producer:

Mario Bava, credited as Mickey Lion, does the first rip-off of THE EXORCIST to be even mildly interesting. Interesting, not good. It is a bizarre, uneasy assimiliation of the exorcism motifs into the Bava formula atmosphere and schloss setting. Actually more like two films spliced together, with the exorcism segments segreated, as Elke Sommer goes through strenuous – and some of the most disgusting – bouts of vomiting and scatology yet depicted. But Bava tries to remain aloof from that– as the rest of his film follows Telly Savalas’ incarnation of the Devil, sucking on a Kojakc Lollipop, as he victimizes a disembodied Sommer by placing her into the madness of a family of sexually depraved aristocrats.

THE HOUSE OF EXORCISM (“La Case Dell’Esorcismo,” A Peppercorn-Wormser Release, 7/76 [c75]). In Color by Movielab. 93 minutes. Produced by Alfred Leone. Screenplay by Alberto Tintini, Alfred Leone. Directed by Mickey Lion (a.k.a. Mario Bava). Filmed as LISE E IL DIAVOLO (“Lisa and the Devil”). With: Telly Savalas, Elke Sommer, Sylva Koschina, Alida Valli, Robert Alda.

NOTE: In the 1980s the unaltered LISA AND THE DEVIL made it to late night TV, where it was trimmed for violence and nudity but more or less intact. The uncut version finally became available in the 1990s on laserdisc and later on DVD, where it was double-billed with HOUSE OF EXORCISM.

Mario Bava: Master of Illusion

[EDITOR’S NOTE: As part of our on-going celebration of Mario Bava this week, we enlisted the aid of Keith Brown, who writes voluminously – and, more important, fascinatingly – on the subject of Italian cinema.]

An Appreciation by Keith Brown of Giallo Fever

If there’s one word which encapsulates the world of Mario Bava’s cinema for me it would probably be irony. Here was someone who virtually had to be pushed into the director’s chair to make his official debut at the age of 45, but thereafter seemed unable to say “no” to just about any project that came his way, racking up 20 or so directorial credits in not quite as many years. Here was someone who went from the poverty-row circumstances of PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965) and KILL BABY KILL (1966) to the major league with Dino de Laurentiis on DIABOLIK (1968), only to find that he wasn’t comfortable actually having money and time available. Here was someone who was given a clean bill of health by his doctor days before his fatal heart attack in April 1980. Here was someone who contrived to die the same week as Hitchcock so that his passing went almost unnoticed, yet he has since been heralded by the likes of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Tim Burton. And, above all, here is someone whose films continually show up the distance between appearances and reality to delight, surprise and shock you: the apparent junkie in BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964) who turns out to be an innocent diabetic; the sinister seeming witch in KILL BABAY KILL whose ministrations are in fact purely beneficient (and whose malign counterpart is the virtual definition of innocence); or, above all, the countless figures whose conceal the basest of desires behind a facade.

If there’s one word which encapsulates the world of Mario Bava’s cinema for me it would probably be irony. Here was someone who virtually had to be pushed into the director’s chair to make his official debut at the age of 45, but thereafter seemed unable to say “no” to just about any project that came his way, racking up 20 or so directorial credits in not quite as many years. Here was someone who went from the poverty-row circumstances of PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965) and KILL BABY KILL (1966) to the major league with Dino de Laurentiis on DIABOLIK (1968), only to find that he wasn’t comfortable actually having money and time available. Here was someone who was given a clean bill of health by his doctor days before his fatal heart attack in April 1980. Here was someone who contrived to die the same week as Hitchcock so that his passing went almost unnoticed, yet he has since been heralded by the likes of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Tim Burton. And, above all, here is someone whose films continually show up the distance between appearances and reality to delight, surprise and shock you: the apparent junkie in BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964) who turns out to be an innocent diabetic; the sinister seeming witch in KILL BABAY KILL whose ministrations are in fact purely beneficient (and whose malign counterpart is the virtual definition of innocence); or, above all, the countless figures whose conceal the basest of desires behind a facade.

Bava worked as a cinematographer and general cinematic jack-of-all-trades prior to making his directorial debut. The two most important films of this period are Freda’s I VAMPIRI (1956) and CALTIKI THE IMMORTAL MONSTER (1959) as on each occasion Bava was charged with completing the film after director Ricardo Freda abandoned ship.

Production circumstances and genre aside, I VAMPIRI and CALTIKI are different: In hindsight I Vampiri emerges as the home-grown founding text for the next quarter century of Italian horror production, freely mixing mad science; gothic and detective thriller motifs. CALTIKI by contrast presents its makers’ engagment with foreign traditions, borrowing liberally from THE BLOB and the Hammer ‘X’ films THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT and X THE UNKNOWN but giving them a distinctively Italian-style makeover in a way that was to also become familiar over the coming years, most obviously with the spaghetti westerns of the 1960s.

It has sometimes been suggested that Bava would never make another film as good as his debut, BLACK SUNDAY (1960). Whether or not you agree with this statement – personally I don’t – it is a fitting testament to the sheer impact of the film itself, whose post-Hammer shocks, beginning with the hammering of a spiked mask onto the witch Asa’s face, were sufficient for it to be denied a release in the UK for close on ten years. BLACK SUNDAY’s other key claim to fame is, of course, that of inaugurating the career of Barbara Steele, the fetish star of 1960s Italian horror, who plays what was to be the first of many dualistic-cum-schizophrenic sado-masochistic roles as the re-incarnated witch and her innocent target Katia.

Had Bava done nothing other than realise Steele’s potential his place in the history books would have been assured. As it was, however, he did much more, following the hallucinatory horror-peplum HERCULES IN THE HAUNTED WORLD (1961), starring Christopher Lee as the Dracula-esque Lyco, with the first giallo to really be worthy of the name, THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1963).The first of Bava’s Hitchcockian films, THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH is also one of his most ironic, self-reflexively exploring issues of fiction and reality as a habitual reader of murder mysteries finds herself plunged into a not dissimilar scenario shortly after arriving in Rome for a holiday and proceeds to misread just about every clue placed before her while somehow muddling through to a happy ending.

There were to be no happy endings in the anthology film BLACK SABBATH. Released in the same year as THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH and THE WHIP AND THE BODY in what was something of an annus mirabilis for Bava, the film makes yet another significant contribution to the formation of modern horror as the first in which evil wins. Yet it also does so in a way that is different from the later likes of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, presenting itself as artificial rather than real. As Boris Karloff, the monster and master of ceremonies, remind us in the coda, there are really no such things as vampires; it’s “only a movie, only a movie…”

Though Steele would have been ideal for the role of Nevenka Menliff in THE WHIP AND THE BODY opposite Lee’s prodigal son who everyone else wishes would just go away, Daliah Lavi proves about as good a substitute as could be imagined. One of Bava’s most challenging films, dealing with themes of sadomasochism and amour fou in a serious and mature manner, critical reaction to the film was muted on account of the drastically recut matinee audience friendly versions which circulated internationally. Never has a retitling – WHAT – been more apt.

It’s impossible to say anything new about BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964): It’s the giallo by which all others are measured and which, for better or worse, inaugurated the body count film. It’s also a stunningly brutal and beautiful work that few if any of its innumerable imitators have been able to match on either counts, let alone surpass on one or both or in terms of overall cinematic intelligence and aptitude.

Unfortunately for Bava audiences in Italy and elsewhere were not quite ready for the giallo at this time, prompting a move into the spaghetti western with THE ROAD TO FORT ALAMO (1964), generally regarded as one of his lesser and less successful films; much the same can be said of Bava’s other ventures into the filone, RINGO FROM NEBRASKA (1966) and ROY COLT AND WINCHESTER JACK (1970).

That Bava found science-fiction more to his liking is evident from PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965). Outdoing ALIEN on a budget that stretched to little more than a couple of papier mache rocks and some dry ice for the alien planet and space Nazi costumes for the crews of the crashed spaceships, the film also features a delicious, characteristically oh-so-Bava sting in the tale…

The following year saw no fewer than four films from Bava: the aforementioned Ringo from Nebraska; the ill-advised Vincent Price vehicle DR GOLDFOOT AND THE GIRL BOMBS; the spaghetti-esque historical adventure KNIVES OF THE AVENGER, which saw Bava reuinted with BLOOD AND BLACK LACE leading man Cameron Mitchell, and KILL BABY KILL. Though its title may be stupid, the film is anything but, cleverly blending giallo and Gothic motifs as the rational scientific investigative hero is forced to realise that the reality of the supernatural, epitomised by the oft-quoted scene in which he pursues a ghostly child and himself through the castle chambers.

The commercial high point of Bava’s career was the aforementioned DIABOLIK. Though hampered by De Laurentiis’s absurd desire to tame the Giussani sisters’ character for the censor and the box-office Bava’s evident understanding of the fumetti aesthetic shines through, resulting in a pop-art masterpiece that’s been identified as the most faithful comics book adaptation by artist and cult film scholar Steve Bissette and referenced by the likes of Burton’s BATMAN and Roman Coppola’s CQ.

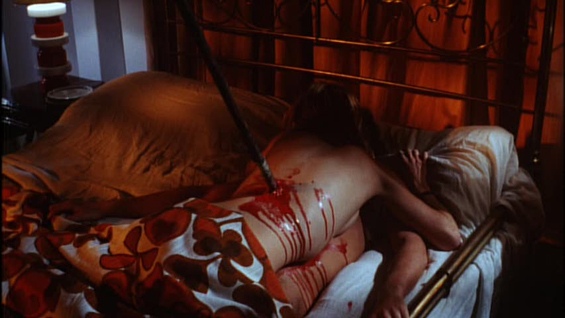

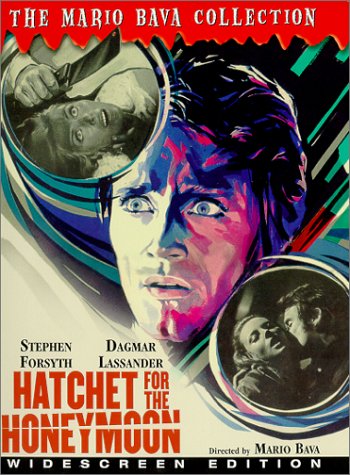

Following DIABOLIK Bava made three intriguing gialli in as many years, the Hitchcockian A HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON (1969) and the BLOOD AND BLACK LACE deconstructions FIVE DOLLS FOR AN AUGUST MOON and A BAY OF BLOOD (1971). Benfitting or suffering from a surfeit of modish designs (look up kitsch or camp in the dictionary and you can almost imagine any frame from Five Dolls appearing as an illustration) and stylistic tropes, they’re films which play with the thriller form and the audience’s expectations. Thus in A HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON our protagonist immediately informs us that he’s a schizophrenic killer, who murders newlyweds and brides to be because with each fresh crime he recalls a bit more of a traumatic incident from his past. Yet the resolution to this trauma is obvious to any viewer who knows their Freud. Similarly in A BAY OF BLOOD we’re given so many suspects, murderers and victims that it soon becomes impossible, if not irrelevant, whodunit. Just about everyone does it or has it done to them, until there were none – and all for a bay whose poisonous nature is foregrounded by a credits sequence into which a fly (a recurring creature in Bava’s work, also showing up in an episode of BLACK SABBATH and HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON) suddenly drops dead.

1972 was a pivotal year for Bava, not so much for the two films he made – the underrated FOUR TIMES THAT NIGHT, which reworks Rashomon as a sex comedy and was almost blocked from release by his former mentor Freda, and the old fashioned if effective gothic romp Baron Blood – as for inaugurating his relationship with Italian-American independent producer Alfredo Leone.

Having produced BARON BLOOD, Leone gave Bava virtual carte blanche on his next film, LISA AND THE DEVIL (1973). It was to be a dream project that quickly turned into a nightmare as Leone held off selling the rights to the film in the hope of better offers, only for prospective buyers to then see the film and realise that its poetic art-horror approach was not what they were after for the grindhouse and drive-in crowds anyway. Seeking to recover his losses, Leone had Bava reluctantly retool the film into the cod-EXORCIST shocker HOUSE OF EXORCISM, the less about which said the better. (Saying that you prefer HOUSE OF EXORCISM to LISA AND THE DEVIL is probably the ultimate heresy as far as the Bava fan is concerned, so if you’re feeling brave at one of the retrospective screenings…)

Bava’s next project was even more ill-fated. KIDNAPPED a.k.a. RABID DOGS a.k.a. SEMAFORO ROSSO (1974/1998) is the film that should have re-established his place at the forefront of the Italian popular cinema, showing that he could do hard-hitting, realistic crime actioners with the best of them whilst still accomodating that distinctive ironic touch. Unfortunately his backers ran out of money and the uncompleted film was impounded, not to be released for over 20 years. The film has been described as RESERVOIR DOGS meets LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT in a moving car. It’s not a bad description and indeed almost undersells it: rough around the edges though the reconstructions may be, KIDNAPPED is that good.

SHOCK followed in 1977. Bava’s last film as a director, it saw his son and long-time assistant Lamberto taking an increasing role and thus presents an intriguing baton-passing from father to son, as a kind of transition point from such forerunners as THE WHIP AND THE BODY, KILL BABY KILL and LISA AND THE DEVIL to its successor MACABRE (1980). Bava’s last work as a cinema magician was providing special effects for Dario Argento’s INFERNO (1980), on which Lamberto served as assistant director. The elder statesman of Italian macabre cinema helped his younger successor make the Italian-produced movie look as though it was set in New York, and he conjured up a wonderful scene of one of the Three Mothers of Darkness materializing out of a mirror. Appropriately, the staging of the shot recalled a similar set-up in BLACK SUNDAY, bringing the Bava horror legacy full circle.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Black Sabbath (1963) – Horror Film Review

[NOTE: Our coverage of Mario Bava, timed with the American Cinemathque’s festival Poems of Love and Death, continues with this look back on one of his most well-loved films.]

Director Mario Bava’s second Gothic horror extravaganza (after years of photographing and/or finishing other directors’ work) is another exercise in style and atmosphere from the uniquely gifted auteur, but it falls short of his official directorial debut, BLACK SUNDAY (1960). A trilogy of terror tales of various shapes and sizes, hosted by (and in one case starring) legendary horror icon Boris Karloff, BLACK SABBATH (known as I TRE VOLTI DELLA PAURA or “The Three Faces of Fear” in its native Italy) runs the gamut from Gothic period piece to contemporary thriller. None of the episodes is without interest, but much of their appeal lies in watching a talented visual stylist applying his skills to create an eccentric, artificial world of the imagination that delights devotees but leaves casual viewer puzzled or indifferent. Only one episode reaches the critical mass that explodes into the kind of absolute terror that will satisfy skeptic and fan alike, but that is more than enough to make this essential viewing.

“THREE FACES OF FEAR” IN ITALY

In its original form, the film begins with Karloff introducing the stories from on top of a artificial-looking mountaintop, with moving lights project on the cyclorama behind him. Looking more like science-fiction than horror, the intro sets of tone of deliberate stylization. Karloff stars in the second episode, but he does not reappear as “himself” until the very end. The three episodes are introduced only by title cards.

Up first is “The Telephone,” a nifty little contemporary thriller about a woman terrified by a series of threatening calls. Gradually it emerges that she was instrumental in getting a gangster sent to prison, but he has escaped to seek revenge. Bava does a wonderful job with the limited space (the episode is set pretty much in a single apartment); his visual flash combines with the lurid story developments (including a lesbian sub-plot) to create something very close to a proto-giallo film (a form of violent, sexy Italian thriller that would emerge full-blown in Bava’s later feature, BLOOD AND BLACK LACE).

The second story is “The Wurdalak,” a highly regarded vampire tale that, despite its reputation, fails to match BLACK SUNDAY. Starring Karloff, this period piece about European vampires is highly is the longest of the three tales, and it has trouble sustaining itself; rather than building to a climax, it runs down like a vampire awaiting the dawn. There is much riding on horseback, but no one really gets anywhere, and for once Bava’s bravura gets the better of him. The exaggerated colors and contrived camera movements are fun to watch, but they suggest an unwanted ’60s drug-induced flashback more than soul-shattering horror.

Finally, everything falls into place with “A Drop of Water.” This short intense tale – of the ill-fate that befalls a woman who steals a ring from a corpse – is one of the absolutely highlights of Bava’s career, a film so strong that it could have stood on its own as a short subject. Easily the highlight of the film, “Drop of Water,” is told with an expert use of lighting and camera angles, creating a remarkable sense of dread that permeates the short running time. The atmosphere is engrossing; the tension is superbly calibrated; and the elaborate visual touches are perfectly integrated. One interior night scene is lit with eye-catching alternating colors; we’re suposed to assume that some kind of flashing neon sign is right outside the window, but it doesn’t really matter. the only important thing is the unnerving effect, which perfectly sets the stage for the appearance of the supernatural. The episode includes one of cinema’s best waking corpses, apparently achieved entirely with a simple mannequin. There is something completely uncanny about its appearance, with a face as disturbing in its own way as Linda Blair’s scarred countenance in THE EXORCIST. Even the audio sends shivers down the spine, with the buzzing of a fly used as a leitmotiv announcing the intrusion of the supernatural.

Responding to concerns from his American distributor that this powerful episode was too intense and downbeat a note for the finale, Bava added a comic finale in which Karloff is seen again, in costume for his character in “The Wurdalak.” In a visual joke that predates AIRPLANE by decades, Bava pulls the camera back to reveal that the “horse” Karloff is riding is just a mechanical contraption on set, with stage hands running around waving branches to represent the “trees” past which he is “riding.”

“BLACK SABBATH” IN THE U.S.

American International Pictures, the distributor that had re-edited Bava’s director debut, THE MASK OF SATAN, and released it in the U.S. under the title of BLACK SUNDAY, got involved with THREE FACES OF FEAR while it was still in production. Salvatore Billitteri, who had handled AIP’S re-editing of BLACK SUNDAY, was on the set (credited as “production assistant”) in order to help tailor the film to AIP’s specifications. Retitled BLACK SABBATH (an obvious nod to BLACK SUNDAY), the result was quite different from the Italian original.

The AIP version replaces Roberto Nicolosi’s typically sparse, almost ambient score with more heavy-handed dramatic music by Les Baxter. Karloff’s original introduction was dropped in favor of a new one, reusing much of the same dialogue, filmed against a black backdrop, with Karloff’s body draped in black to suggest a head floating in limbo. Additional footage was shot by Bava, with Karloff introducing each episode.

Unfortunately, the episodes were reshuffled. The truly wonderful “Drop of Water” instead of serving as the climax, was bumped up to the beginning, where it makes everything that follows seem anti-climactic. The film was left to end with the over-rated “Wurdalak” episode. Ironically, the comic epilogue (which had been added at the last minute to address AIP’s concerns about ending the film with “Drop of Water”) was no longer needed. The AIP version substitutes an outtake of Karloff as Gorka, rearing up on his horse and riding away.

Most notably, the episode entitled “The Telephone” was radically transformed. Originally a straight thriller, the episode lost its lesbian subplot, and dialogue dubbing turned the escaped gangster into a ghost or a walking corpse (it is not clear which). To establish the supernatural element, Bava even provided a special effects insert shot for the AIP release: a note slipped under a door seems to write itself before our eyes, as if a ghostly invisible hand were at work. The change makes little sense, because the episode’s action remains the same, climaxing with the gangster’s death by stab wound.

AIP’s revised BLACK SABBATH is far from being a complete desecration, but it is definitely inferior to the Italian original. “The Telephone,” in particular, has suffered in critical appraisals because of its illogical supernatural element, which leaves viewers wondering how a ghost can be stabbed to death with a knife. Fortunately, Bava’s directorial stylings were enough to make the film fun viewing even in altered form, and the AIP cut earned many fans over the years, who eventually discovered the “director’s cut” when it finally emerged on DVD.

In the final assessment, THREE FACES OF FEAR/BLACK SABBATH is a fan film. It features all the unique, eccentric elements that clearly define it as a “Mario Bava Movie.” For the true connoisseur, this makes it as delectable as a fine vintage wine, worth savoring for the distinctive bouquet lacking in more popular, mass-produced products. But unlike BLACK SUNDAY, Bava’s follow-up does not transcend the genre in a way that demands – and earns – respect and admiration even from the non-believers. Layered with colorful decor like a finely frosted cake, the film is more of a visual delight than a fully satisfying experience. The rococo richness is definitely enjoyable, but it can’t quite hide that the cake has not risen as high last time.

BLACK SABBATH (a.k.a. I Tre Volti Della Paura [“Three Faces of Fear”], 1963). Directed by Mario Bava. Screenplay by Mario Bava, Alberto Bevilacqua, Marcello Fondato; based on stories by Ivan Chekhov, F.G. Snyder, and Aleksei Tolstoy. Cast: Boris Karkoff, Mark Damon, Susy Anderson, Michele Mercier, Lidia Alfonsi, Jacqueline Pierreaux.

RELATED ARTICLES:

Hollywood Gothique: Mario Bava Film Fest

The American Cinematheque launches its film festival Mario Bava: Poems of Love and Death at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood tonight. Up first is a double bill of BLACK SUNDAY (a.k.a. “The Mask of the Demon,” 1960) and BLACK SABBATH (a.k.a. “Three Faces of Fear). Director Joe Dante (THE HOWLING, Showtime’s MASTERS OF HORROR) will introduce the event.

Bava was a cinematographer-turned-director, who also knew how to do old-fashioned, in-camera special effects. In the 1960s, he used his visual skills to craft a series of delirious beautiful films of various shapes and sizes, but his greatest achievements were in the realm of cinefantastique: Gothic horror, giallo thrillers, science-fiction, and mythical fantasy.

The Cinematheque’s festival runs through March 23. Besides Dante, directors Eli Roth (HOSTEL) and Ernest Dickerson (TALES FROM THE CRYPT: DEMON KNIGHT) will introduce many of the screenings. The schedule (listed below the fold) includes most of the major highlights of Bava’s career. Take note: some are not available on DVD! Continue reading “Hollywood Gothique: Mario Bava Film Fest”

Black Sunday (1960): A Retrospective

Widely regarded by fans as a genre masterpiece, BLACK SUNDAY is a magnificent work of black-and-white horror, filled with wonderfully atmospheric effects and punctuated by moments of brutality quite grizzly for their time. Also known as “The Mask of Satan,” “Mask of the Demon,” or “Revenge of the Vampire” (depending on the country of release), the film simultaneously harkins back to the Universal classics of the 1930s and emulates the then-contemporary verve and dynamism of Hammer Films productions like HORROR OF DRACULA (1958). The result is a unique piece of Gothic visual poetry that retains its power to thrill and entertain with all the tenacious vivacity of its centuries-dead vampire-witch, who refuses to lie quietly in her grave.

In 17th century Moldavia, Princess Asa (Barbara Steele), along with her servant Igor Yavutich (Arturo Dominici), is sentenced to death for practicing witchcraft—by having a spiked mask nailed onto her face. Two hundred years later, Dr. Gorobec (John Richardson) and Dr. Kruvajan (Andrea Checchi) stumble into her crypt when their coach breaks down on the way to a convention. Kruvajan cuts his hand while defending himself from a bat. On their way out, they meet Asa’s descendant, Princess Katia (also Steele), whose father (Ivo Garrani) lives in fear that the witch’s curse will claim the life of his daughter.

Later that night, Kruvajan’s blood revives Asa. Now an undead but immobile vampire, Asa summons Yavutich from the grave; her servant lures Kruvajan back to the crypt, where Asa drains the rest of his blood. Sought to help Katia’s ailing father, the vampirized Kruvajan kills him instead, then disappears.

Dr. Gorobec, who has fallen in love with the young princess, offers to clear up the mystery, with the help of a local priest (Antonio Pierfederici). They trace Kruvajan to the cemetery and destroy him by driving a wooden stake through his eye. Meanwhile, Yavutich has abducted Katia, bringing her to Asa’s tomb, where the vampire-witch drains off her lifeforce—the last ingredient she needs to become fully mobile. Returning to the crypt, Gorobec almost stakes the unconscious Katia—until he sees the cross around her neck. When the priest arrives with a throng of villagers, Gorobec uses the cross to reveal Asa’s true identity. The mob burns her at the stake; as she dies, her lifeforce drains back into Katia, reviving her for the happy ending.

The script, loosely based on a short story by Nikolai Gogol called “The Vij,” has a plot hole or two; for example, why does Asa need Katia’s life-force to become mobile, while Yavutich is fully functional from the beginning? Fortunately, the carefully crafted mise-en-scene sweeps away any reservations, providing numerous memorable images: the stone coffin that explodes to reveal Asa’s revived body; the pockmarked face of the witch after the spiked Mask of Satan has been removed; the eerie, slow-motion coach ride, with secondary vampire Igor Javutich lashing the horses forward (an obvious visual quote from DRACULA’s coach ride, yet in many ways superior). Director Mario Bava (who also photographed) uses trick photography and lighting effects to create a stark Gothic atmosphere, then injects decidedly adult elements of violence and eroticism. More than anything, the film is an exercise in visual style, demonstrating that camera movement, composition, and lighting can combine to create a splendidly cinematic work that far outshines any narrative weaknesses.

TIME CAPSULE

To a large extent, BLACK SUNDAY’s reputation rests on the convergence of two cult figures: Mario Bava and Barbara Steele. Bava was a talented cinematographer making his directorial debut, and Steele was a British actress who had moved to Italy after a career in Hollywood failed to work out. Bava went on to become a prolific director of horror, science fiction and fantasy films, and Steele became the reigning Queen of Horror (at least in Italy)—the closest cinema has ever produced to a distaff version of Bela Lugosi or Christopher Lee.

At the time BLACK SUNDAY was shot in late 1959 (under the title La Maschera Del Demonioin Italy), the traditional horror film had only recently come back in vogue after a decade dominated by science fiction monster movies. Having completed two films left unfinished by director Ricardo Freda, I VAMPIRI (1956) and CALTIKI THE IMMORTAL MONSTER (1959), Bava finally was given an opportunity to direct an entire feature film by himself when CALTIKI’s executive producer, Lionello Santi, showed his appreciation by offering Bava his choice of projects. Bava selected Nikolai Gogol’s “The Vij,” which was then adapted into a screenplay by Ennio De Concini and Mario Serandrei. About the only story element that survives in the film is the concept of a beautiful vampire-witch who emerges explosively from her coffin.

For the dual role of Asa/Katia, Bava selected British actress Barbara Steele, who had previously appeared with her co-star John Richardson in BACHELOR OF HEARTS (1958) while the two were under contract with J. Arthur Rank Productions in England. “It’s very odd that we both ended up being in the film,” she says. “I couldn’t understand why I was there. I had a little spread in Life magazine, and I think Mario Bava saw one of these photos. Anyway, he invited me to go to Rome, where I’d never been, and I must say I’ve never recovered. It’s a very small city, but it had such an optimistic and rich energy. It was an incredibly vibrant and voluptuous period: sunshine and jasmine and gorgeous men! So it was like a love fest really—especially coming from a repressed English environment.”

No doubt part of the reason for the casting decision was the Italian film industry’s concern with international market appeal. The casting of British actors in the leads would make his film seem more in the vein of recent Hammer productions like HORROR OF DRACULA (1958). And of course, shooting the film in English would make it easier to export to the United Kingdom and the United States. As Clint Eastwood would later do in his Westerns for director Sergio Leone, both Steele and Richardson spoke English while filming an Italian movie in Italy—a fact that is clearly visible when watching the film, even though both actors (unlike Eastwood) have been dubbed with other voices.

The Galatea-Jolly production then shot on the Titanus Studios in Rome, where Freda and Bava had worked on I VAMPIRI. “It was strange to go from this incredible Italian energy to this very dark, tomb-like set—which was totally monochromatic,” Steele recalls. “It’s supposed to take place in Russia, because it’s taken from a story by Gogol, but I must say, the film feels incredibly Nordic. It was very familiar, this landscape Mario Bava drew, because it reminded me of where I grew up in Scotland and Wales, a wild Gothic environment with wild storms. Looking at it, it’s just impossible to imagine that this film was shot in Italy! It’s extraordinary. It’s just inspired, really.”

Bava exploited Steele’s physique for the remarkable scene wherein the prostrate Asa seduces Kruvajan, her chest heaving erotically beneath her black gown while her voice urges him to approach. “They were so frantic that people wouldn’t notice,” she laughs. “I mean, I hadn’t had to breathe like that since I saw the doctor when I was five: Inhale! Exhale!”

Once filming was completed, different versions were prepared in the editing room for domestic release and for export. The Italian language prints contain one scene not present in any other version, a brief dialogue between Katia and her father by a fountain, wherein he expresses concern for her state of mind and promises to take her away from the family’s gloomy ancestral castle. Apparently, the dialogue is a remnant from an earlier script draft that was dropped from other cuts of the picture because it no longer fit; in the Italian version, this daylight scene is awkwardly intercut with the nighttime sequence of Igor Javutich’s resurrection!

An “international” version of THE MASK OF SATAN (as it was called) was then completed for export to English-speaking territories like the U.S. and England, with dubbing credited to George Higgens III. As was often the case in Italian film from this period, the original actors had their voices replaced even in their own language; neither Steele nor Richardson can be heard in any version.

“The dubbing ended up as a plus for him and a minus for me, because in actual fact he has a much lighter voice,” says Steele of her co-star. “The deeper voice gave him a great presence, I thought.” Fortunately, the dubbing process could dim but not destroy the effectiveness of Bava’s visuals.

The international version of MASK OF THE DEMON was eventually released in Britain in 1968 under the title REVENGE OF THE VAMPIRE. Prior to that, Americans saw a slightly different version in 1961, when American International Pictures released the film as BLACK SUNDAY. AIP co-founders Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson had seen the film in an Italian screening room during the spring of 1960. Arkoff thought it was “one of the best horror pictures I had ever seen.”2 Nevertheless, AIP edited, redubbed, and rescored the film for its U.S. release.

It is a testament both to the power of Bava’s original film and to AIP’s handling of the American release MASK OF THE DEMON survived its transformation in BLACK SUNDAY. The U.S. version is not a complete hatchet job but a reasonably careful revision that removes a few sentimental moments, improves the lip synchronization of the vocal performances, and substitutes new music by the late ultra-lounge composer Les Baxter. The most serious flaw is an overabundance of caution that led to the trimming of several crucial moments of horror.

The result was fairly effective. The new dialogue actually follows the original English-language script more closely, and the voices are relatively indistinguishable from those in the international version—except for that of Constantine, Katia’s younger brother, who now speaks with the unmistakable voice of Peter Fernandez, who later dubbed the title character in the Japanese animated series SPEED RACER. Baxter’s score is too insistent upon emphasizing the suspenseful moments, but his romantic theme for Katia is a bit more subtle than Roberto Nicolosi’s: while using a similar arrangement of piano and strings, Baxter tones down the excess, with a few simple chords on the keyboard creating a suspended feeling somewhat less hokey than the original.4

The result became a big success not only in the United States but also around the world, and helped raise interest in releasing subsequent Italian horror efforts. “I don’t know who it made money for,” says Steele. “All I know is that several years ago I was in a screening room watching a private screening, and some distributor came up to me and said, ‘I just adore you.’ I asked him why, and he said, ‘We distributed BLACK SUNDAY in England, and it made eight to ten million dollars.’”

Despite its success, BLACK SUNDAY never generated a sequel. However, it was remade in 1989 by Bava’s son Lamberto, who had established his own career as a horror director with films like DEMONS (1985) and DEMONS 2 (1986).

DVD DETAILS

Although clearly a product of its era, BLACK SUNDAY has not dated badly. The truncated AIP version, known to American fans, remains a powerful work, marred only slightly by the inevitable problems that arise in the process of dubbing and recutting a foreign import. Thanks to Image Entertainment’s DVD release, the film is now available in all its original glory, with its missing footage and original music intact. This international version of the film (bearing the original title THE MASK OF SATAN) restores a certain punch that increases the film’s effectiveness by contemporary standards.

The execution of Princes Asa has far more impact thanks to two shots that are allowed to run longer than in the American print. In the first, the witch has the mark of the devil branded into her flesh (actually a wax stand-in), and instead of cutting away as the brand is applied, the camera lingers until we can see the result. In the second restored shot, one of cinema’s great moments of brutality is rendered even more horrific: as the Mask of Satan is hammered onto the witch’s face with a mallet large enough to knock a mule unconscious, the shot no longer quickly fades to black but instead shows a fleeting moment of blood spewing from beneath the mask, driven forth by the impact. The credits that immediately follow are effectively superimposed over a medium shot of the titular Mask of Satan (instead of being seen merely against some nondescript flames), and we can see that the witch is still alive and breathing, with blood running down her neck.

The true highlight of the international version emerges after Asa has been reawakened in her tomb. Alive but still immobile, she draws her first victim to her prostate body with the mesmeric influence of her eyes. Steele’s heavy breathing in this scene is almost orgasmic, but the American print faded out on a close up of her face before she made contact with her intended victim. In THE MASK OF SATAN, at last you can see the lingering kiss that climaxed the scene.

Still later, there is an additional brief romantic interlude between Katia and Dr. Gorobec, who tries to convince the young princess not to give in to despair despite the horrible events occurring around her. The final restored moments occur near the climax, when Gorobec speaks several more lines of dialogue lamenting the apparent death of Katia, after her life-force has been drained by her vampiric ancestor. This helps to make Katia’s revival, as Asa is burned at the stake, seem like more of a surprise and less of a foregone conclusion.

The print used for the DVD transfer is in great shape, with only an occasional scratch here and there; the image, letterboxed to a 1:66 ratio, is clear and sharp, as is the Dolby Digital, monaural soundtrack. The special features are impressive as well: a brief Mario Bava biography, filmographies for both Bava and Steele, a theatrical trailer, and a gallery of photos and posters. The latter includes rare behind-the-scene shot of Bava being strangled by Arturo Dominici, who plays Javutich. Also of interest is a shot of Dominic modeling his vampire fangs, which are nowhere seen in the film. The disc also contains a transcript of the dialogue (translated by Christopher S. Dietrich and Lucas) from the missing scene between Katia and her father. Of course, it would have been nice to see the footage as a supplemental scene, but the transcript is an adequate substitute.

Tim Lucas’s audio commentary is a highlight of the DVD. He spews out trivia and behind-the-scenes anecdotes almost faster than you can keep track of, yet somehow, he never bores you with his expertise. He even does some interesting second-guessing about how some scenes in the final cut may have survived from previous drafts of the script; for example, Lucas suspects that the original intent may have been to have Asa replace and impersonate Katia at a much earlier point in the narrative. Unfortunately, Lucas does tend to overlook the film’s minor flaws, which mostly consist of a few risible moments in the dubbing. (My personal favorite: Dr. Gorobec advises the torch-bearing villagers on how to distinguish Asa from Katia: “She’s the witch. Don’t’ be deceived by her face—look at her body!”)

Overall, Image’s DVD is about the best presentation imaginable of the original version of the late Mario Bava’s masterpiece, short of getting an audio commentary from Barbara Steele herself. Unfortunately, this we are likely never to get, as Steele claims that trying to remember details of the filming is as hopeless as trying to remember the details of her high school prom. Nevertheless, in recent years she has come to acknowledge the film’s greatness in a way that she seldom did when while fighting the typecasting that resulted from her performance in it: “As an actress, it’s not exactly something that lets you do any tour-de-forcing,” she explained years ago. After reviewing the film, however, she has a more balanced view:

“Mario Bava made a brilliant, brilliant film, and I’m deeply grateful,” she says. “BLACK SUNDAY looks so exquisite to me as a film, today; frame for frame, it looks so beautiful. It’s like a Rembrandt. Visually, it is stunning, and that’s what cinema is: visuals and atmosphere. Really, it could be an incredible Silent Film—you could take the soundtrack right off, because it’s such a visual masterpiece.”

BLACK SUNDAY (a.k.a. La Maschera del Demonio [“Mask of the Demon”], 1960). Directed and photographed by Mario Bava. Screenplay by Ennio De Concini and Mario Serandrei, based on “The Vij” by Nikolai Gogol; English dialogue by George Higgins. Cast: Barbara Steele, John Richardson, Andrea Checchi, Ivo Garrani, Arturo Dominici, Enrico Olivieri, Antonio Piefederici, Tino Bianchi, Ciara BIndi, Mario Passante, Renato Terra.

[serialposts]

More Mario Bava on the way

Mario Bava was one of the most important figures in the history of horror-fantasy cinema, but during his lifetime few of his films reached American shores in uncut form. Thanks to the modern miracle of home video technology fans can now enjoy the director-cinematographer’s works as they were meant to be seen. Earlier this year, Anchor Bay entertainment released the five-disc “Mario Bava Collection – Volume 1.” On October 23, they will follow up with Volume 2, featuring new transfers of eight films, along with new bonus features. Titles include LISA AND THE DEVIL (along with its bastard permutation HOUSE OF EXORCISM), BARON BLOOD, BAY OF BLOOD, 5 DOLLS FOR AN AUGUST MOON, KIDNAPPED (a.k.a. RABID DOGS), ROY COLT AND WINCHESTER JACK, and FOUR TIMES THAT NIGHT. Read complete details below the fold. Continue reading “More Mario Bava on the way”

Mario Bava was one of the most important figures in the history of horror-fantasy cinema, but during his lifetime few of his films reached American shores in uncut form. Thanks to the modern miracle of home video technology fans can now enjoy the director-cinematographer’s works as they were meant to be seen. Earlier this year, Anchor Bay entertainment released the five-disc “Mario Bava Collection – Volume 1.” On October 23, they will follow up with Volume 2, featuring new transfers of eight films, along with new bonus features. Titles include LISA AND THE DEVIL (along with its bastard permutation HOUSE OF EXORCISM), BARON BLOOD, BAY OF BLOOD, 5 DOLLS FOR AN AUGUST MOON, KIDNAPPED (a.k.a. RABID DOGS), ROY COLT AND WINCHESTER JACK, and FOUR TIMES THAT NIGHT. Read complete details below the fold. Continue reading “More Mario Bava on the way”

Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970) – Horror Film Review

“Reality is more horrible than fiction,” a character observes in this stylish Spanish/Italian shocker, yet director Mario Bava keeps pumping for the fantasy – oriented delirium at the core of the cut-and-slash dramas so dear to his heart. Here he forsakes the mystery element usually associated with his blood-drenched projects to inspect the tormented psyche of a handsome, well-heeled psycho played by Stephen Forsyth, who unlocks his troubled past by hacking up young women, usually on their wedding night. Continue reading “Hatchet for the Honeymoon (1970) – Horror Film Review”

Twitch of the Death Nerve (1971) – Horror Film Review

[Editor’s Note: This review, written by Jeffrey Frentzen, originally appeared in the Fall 1975 issue of Cinefantastique (4:3).]

[Editor’s Note: This review, written by Jeffrey Frentzen, originally appeared in the Fall 1975 issue of Cinefantastique (4:3).]

By Jeffrey Frentzen

Mario Bava’s ANTEFATTO (“Before the Fact”), produced in Italy in 1970, was picked up for domestic release by Hallmark in 1973, playing second-feature to other Hallmark bloodbaths like MARK OF THE DEVIL and LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT. The latest Bava work available for American viewing is the director’s most complete failure to date, heaping graphic violence onto one of his more ridiculous scripts. If you were appalled by the gore and slaughter of BLOOD AND BLACK LACE, this latest film contains twice the murders, each one accomplished with an obnoxious eye for detail (faces split open in loving close-up, decapitation, and murder of the axe variety). The raw violence is only an excuse to propel a silly story reminiscent of an Edgar Wallace cloak-and-dagger mystery.

Bava is a talent, despite the claustrophobic limitations of his plot. He has always had a fascination for beautifully decorated interiors and fog-shrouded, wispy exteriors, all filmed in prevalent hues of grey and blue. It is unfortunate that his fascination extends also to synopses filled with unabashed stupidity. His screenplay abounds with an execrable soap-opera quality that somehow overpowers even the excessive bloodshed. Bava shares the blame this time with Carlo Reali for developing the slight story idea, involving a group off heirs to a valuable land tract who are murdered one by one, supposedly by someone who wants the land for himself. Red herrings are ever-present, and serve as the only interest keeping the plot in motion, but nothing really redeems the dumb storyline. There is a cleverly calculated “surprise” ending that comes far too late to make any difference. Bava seems to make a point of confusing the viewer.

There are, of course, those shining moments which distinguish any Bava film: the opening scene, accompanied by a sumptuous, well-orchestrated score by Stelvio Cipriani (the only consistently good quality in the film), in which the dim figure of a woman in a wheelchair is stalked and strangled; the swimming sequence wherein a girl bumps into a floating corpse on the lake and is killed for her discovery. Bava is a creative talent despite his weaknesses. His photography is moody and effective, and his pacing is good in spite of a defective plot. Here is a director and expert cinematographer whose work is constantly being maimed by the unreasonably low standards set by his own lousy scripts.

Copyright 1975 by Jeffrey Frentzen. This review originally appeared in the Fall 1975 issue of Cinefantastique (4:3). As time permits, other articles from this issue will be archived under the heading for September 1975.

TWITCH OF THE DEATH NERVE (released in Italy as Ecologia del delitto [“Ecology of Murder”], also known as “Bay of Blood,” Hallmark, 1973). In Color. 90 minutes. Produced by Guiseppe Zacciarello (Nuova Linea Cinemato¬graphica). Directed and photographed by Mario Bava. Screenplay by Bava and Carlo Reali. Cast: Claudine Auger, Luigi Pistilli, Claudio Volonto, Laura Betti, Ana Maria Rosati, Brigitte Skay.

RELATED ARTICLES: Bay of Blood Review