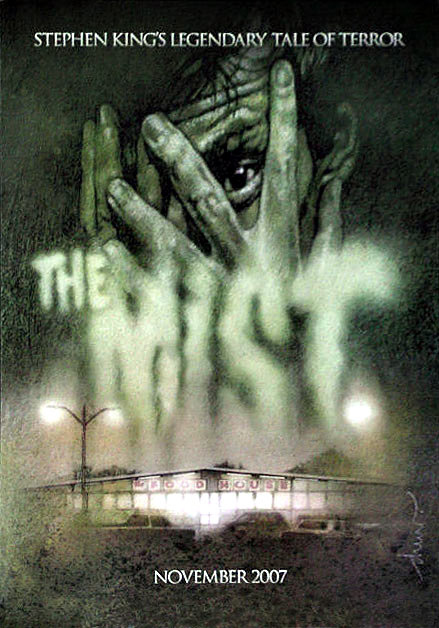

Writer-director Frank Darabont’s adaptation of Stephen King’s memorable novella is a frustrating mix of the sublime and the ridiculous. Perhaps that is not fair; it may be that certain aspects of THE MIST only seem dim because they stand side-by-side with material that shines so much brighter – in the same way that sunspots look dark against the surface of the sun. In any case, the result is a disappointment that nearly achieves greatness, only to fizzle and fade out.

The set up has a group of small town neighbors head to the local grocery store to stock up after a big storm knocks out the power. A strange mist, heading from the direction of the local military base, envelopes the store. Iit soon becomes apparent that something very dangerous – and deadly – is lurking in it, ready to devour all who are fool-hardy enough to wander into its murky darkness.

Initially, Darabont seems perfectly in control of the material. He stays faithful to the source while brightening it up with little cinematic touches that make the story work as well on screen as it did on the page. The eerie feeling of anticipating – but not being able to see – the threat outside the store provokes the kind of fear that sends chills down your spine.

Even better, the drama of the situation is rendered in completely believable detail, with a believable cast of characters who bond, take sides, get on each other’s nerves, try their best, and make mistakes – all without ever seeming as if they are being manipulated by the script to generate “conflict.” Darabont seems to be crafting a film meant to stand beside the truly great horror films – the ones wherein you actually believe what is happening, instead of sitting back and chortling while the victims get picked off one by one.

The brilliance of this approach begins to dim almost as soon as the monsters appear. The first encounter happens in a loading dock, where some fools open the metal bay door and giant tentacles get in. The computer-generated effects look like really excellent, very good looking graphics for a computer game, but there is little convincing or visceral about them.

Technical problems aside, it seems too early to be showing them so clearly: the real thrill of the mist is wondering – not seeing – what lurks therein. One suspects that someone, somewhere, grew concerned that audiences would get bored waiting to see a monster, so one was served up as soon as possible.

The biggest problem, however, is the damage to credibility: the tentacles (which are offered up like the tip of an iceberg, suggesting something much bigger outside the loading bay) are obviously too big and strong to be stopped by the closing of the door. In effect, we immediately know the monsters could get in whenever they want; if they hesitate, it is only because the screenplay tells them to, in order to stretch the story to feature length. From that point on, we are really watching an anything-goes monster movie, regardless of the attempts to elevate it with good writing and acting.

Which might be acceptable if it were a good monster movie, but the monsters are not very impressive (one bug-eyed insectoid critter almost looks cute). On top of the unconvincing CGI, Darabont seems unable to direct the horror scenes: when the monsters attack, he cannot orchestrate the mayhem in an organized way, building to climaxes; everything just sort of happens in one big mess.

Crazy cutting underlines the problem. During what is supposed to be a major set-piece, one incompetent idiot manages to set himself – instead of a creature – on fire. While the stuntman leaps about earning his pay doing a full-body burn, the editor cuts away to some other action for what seems like several minutes, then cuts back to the burning man – and yes, he is still burning, as if only a few seconds had passed.

For awhile, the performers keep us involved even as the horror wanes. Contrary to the typical genre formula, this is one fright flick in which the human drama easily outshines the monsters. Thomas Jane is excellent in the lead, carrying the film on pure acting ability (a more well-known star might have over-powered the role with his established persona). You are on his side from frame one, and he keeps you there. Andre Braugher is strong as the big-city lawyer who thinks the locals are trying to make a fool of him; even when the character is, literally dead wrong, you understand and believe him, instead of dismissing him as the standard “too-stupid-to-live” moron usually scene in this kind of film.

Unfortunately, even this quality fades in the second half when Mrs. Carmody (Marcia Gay Harden) emerges as the main antagonist. Imagine Carrie White’s mother, and you get the idea: preaching fire and brimstone, she insists that the monsters are God’s punishment, and she will save the sinners around her through expiation and sacrifice.

The problem is that Harden, although a talented actress, does not have the charisma or mesmerizing persona to make us believe she could convince anybody of anything. Instead of shining a light on how someone like this could emerge as a powerful force in a time of crisis, the film simply assumes that, when people get scared, they will believe just about anything. Well maybe, but that does not explain why no one else in the supermarket is capable of mounting a serious challenge to her ramblings – especially when nothing in the film has indicated that any of these people are receptive to her message.

It hardly helps that we know little or nothing about the background characters. Mrs. Carmody’s followers are mostly extras and bit players dong what the script tells them to; otherwise, there would be no second act crisis. The film gives us a glimpse of only one character’s conversion, Jim Grondin (William Sadler), who feels guilty because his initial skepticism led to the death of a box boy. This guilt is not really enough to sell his transition; he always seems like someone more like to tell Mrs. Carmody to stuff a sock in it.

Around the time Mrs. Carmody calls on her followers to sacrifice a young boy, we know we are fully into movie-movie territory. The early dramatic conflicts reflected previous tensions – old wounds re-opened under desperate circumstances – that made the characters’ actions believable, even when we knew they were making a mistake; here, however, there are no old scores to settle, no seeds planted that would make us believe old friends and neighbors would turn on each other this way. We’re barely a step removed from the Grindhouse, but at least exploitation movies have the crude power of exploitation fueling their wild scenarios. Lacking that, THE MIST has trouble elevating Mrs. Carmody into a truly terrifying antagonist; instead, she comes across as an annoying blabbermouth, and as much fun as it is when someone finally shuts her up, you have to wonder why it took so long.

One also wonders why it took so long to ask the military to explain what is happening. King’s novella had the stricken characters assume that some kind of experiment had gone terribly wrong up at the base; Darabont puts three soldiers in the store, then barely has them do anything (they mostly sit on the sidelines, even when the proverbial shit hits the fan and a little military training might come in handy). They are included only so that one of them can blurt out an explanation for the mist late in the second act, something about an experiment to open a window into another dimension. It is hardly justifies their presence, but apparently it was decided that the movie needed some kind of explanation.

If the film dimmed in its second act, it more or less deliberately turns off the lights in the third. A small group of survivors make a break for it, hoping to find a way out of the mist. If they had watched NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, they might have known these escape attempts do not turn out well. King’s novella more or less borrowed the ending from Hitchcock’s THE BIRDS, with the characters heading off into the unknown and leaving it up to the reader to wonder whether there was any safety over the next hill. Oh, and along the way, they saw God…

Well, not exactly, but it almost seemed so. Early on, the novel’s protagonist and narrator (an advertising artist on the page, turned into a movie poster artist in the film) had a dream in which he saw God striding like a colossus through the land, the earth rumbling beneath his feet. During their trek on the road, the small group of survivors are awestruck by the appearance of a monumental monster striding across the road, towering above them in a way that made you think the artist’s dream had come true. King’s point was that the monsters in the mist were not just scary and lethal on a small-scale level; they were the new lords of the Earth, and there was little hope of finding safe haven anywhere.

Darabont bungles the scene; he retains the punchline but omits the set-up, so all we are left with is a pretty nifty effect of a giant monster crossing the road. Problem is, by this point, we have seen so much of the monsters flitting in and out of the mist – some of them looking pretty big – that this is not a climactic revelation; it is simply more of the same.

With this climactic moment seriously muted – and apparently unwilling to left the film end on King’s ambiguous note of optimism and despair – Darabont opts to supply a different climax. In a single moment of colossal misjudgement, he pretty much douses that last remaining rays of light in the film, turning everything to blackness – and for no good reason.

The new ending is arbitrary and pointless – kind of like a TWILIGHT ZONE twist gone bad. If you are the least bit sensitive to – or cynical about – heavy-handed irony, you will see the surprise coming. In its own way, it has a certain effectiveness, and it might have worked appended to a half-hour short subject. After asking an audience to sit through an entire feature, however, it is just barely short of an insult, a poke in the viewer’s eye.

The only good thing about the ending is that it absolves the viewer from having to wrestle with conflicting feelings over the strengths and weaknesses of the film. When a filmmaker is willing to snuff out his own sputtering candle, it becomes pointless if not outright impossible to retain any respect for the previous flashes of brilliance. Yes, THE MIST began by showing signs that it could have been great, but it winds up being not even good. Somewhere along the way, Darabont just got lost in the fog, and he never found his way out.

NOTE: Typically – and all too predictably – Darabont’s misfired ending has been embraced by some because it is considered a “bold” and “non-Hollywood.” It is worth pointing out that inserting an anti-cliche is not necessarily an improvement over the cliche and that it is foolish to call an ending bold when that ending is ridiculous. Thomas Jane’s character could have saved himself a lot of grief if he had simply thought to turn on his car radio. After all, he and his fellow survivors are driving away from the store in hope of finding safety somewhere, so why are they not listening for some sign that there are other survivors out there? Because that would short-circuit the new ending. The characters behave like idiots, so that Frank Darabont can stage his “surprise” ending. This is not bold; it is simply bad.

THE MIST(2007). Directed by Frank Darabont. Screenplay by Darabont, based on the novella by Stephen King. Cast: Thomas Jane, Marcia Gay Harden, Andre Braugher, Toby Jones, William Sadler, Gregg Brazzel, Alexa Davalos, Walter Fauntleroy, Nathan Gamble.