One of the most important works in the history of cinefantastique is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. Although not as widely read as it deserves to be, the novel has had a huge impact that lives on to this day, thanks to the many science fiction film and television adaptations, beginning with the 1925 silent version, which established the template for the many prehistoric monster movies that followed, including 1933’s KING KONG and 1997’s THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK. If you have ever seen a movie about explorers discovering an extinct species in some newly discovered land and/or bringing it back to civilization, where it escapes and goes on a rampage, you have Doyle – and the 1925 THE LOST WORLD – to thank.

One of the most important works in the history of cinefantastique is Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. Although not as widely read as it deserves to be, the novel has had a huge impact that lives on to this day, thanks to the many science fiction film and television adaptations, beginning with the 1925 silent version, which established the template for the many prehistoric monster movies that followed, including 1933’s KING KONG and 1997’s THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK. If you have ever seen a movie about explorers discovering an extinct species in some newly discovered land and/or bringing it back to civilization, where it escapes and goes on a rampage, you have Doyle – and the 1925 THE LOST WORLD – to thank.

Published in 1912, Doyle’s The Lost World arrived too late to accurately be labeled “Victorian,” but it has much in common with the Victorian-era science fiction literature of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, not to mention the adventure stories of H. Rider Hagard. As with Verne, the story is a sort of travelogue adventure to a mysterious land (in this case a plateau in South America, cut off from the forces of evolution that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs throughout the rest of the world). As with Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle uses the story to raise the issue of human evolution (at one point, the physical appearance of the books’ protagonist is pointedly compared to that of the leader of a tribe of ape-men, implying that the gulf separating modern man from his primitive ancestors is not so great after all). As for Haggard, he has pioneered the “lost civilization” adventure story with King Solomon’s Mines in 1885, but but Doyle went him one better by populating his lost world with dinosaurs. (To be fair, Verne had previously used the idea of prehistoric animals surviving into modern times in Journey to the Center of the Earth).

The great thing about The Lost Word – besides dinosaurs, of course – is that the adventure story is told with wit and humor. Arthur Conan Doyle improves over the work of both Verne and Wells, whose vivid imaginations concocted some amazing adventures but sometimes fell flat in terms of style and/or characterization. Doyle, on the other hand, was the creator of Sherlock Holmes: he knew the value of eccentric, acerbic characters; and in the person of the book’s protagonist, Professor Challenger, the author almost outdoes the intellectual arrogance of the more famous detective, creating a personality at once temperamental, admirable, and even humorous. Equally clever is the handling of the book’s narrator, Edward Malone, an Irish journalist who is understandably terrified of each new danger that presents itself – but who refuses to reveal his fear to his English compatriots, forcing himself to swallow his fear and face each new threat with a brave face that belies his inner turmoil.

In fact, the characterizations and dialogue of the first few chapters are so delightful that a reader is immediately hooked, long before the expedition has set sail for the Amazon – a rare example when the opening expository section of a story is as entertaining as the exciting adventure that follows. An early highlight is Malone’s attempt to finagle an interview with the reclusive, abusive Challenger, whose wife warns the reporter about the dire consequences of rousing her husband’s temper (“Get quickly out of the room if he seems inclined to be violent… If you find him dangerous – really dangerous – ring the bell and hold him off until I come”). The scene turns into a hilarious brawl with Challenger and Malone rolling out the door and into the street, where a policeman offers to arrest the professor until Malone admits he was at fault, his honesty having the side effect of earning Challenger’s respect

Once on route, the story of The Lost World does somewhat bog down in a familiar pattern of Jules Verne-like descriptions of every inch of territory charted on the way to finding the dinosaurs that are the book’s real selling point. There is also an inexplicable plot twist, with Challenger first sending the expedition off without him, then suddenly showing up to take over after Malone and company have reached South America. Why the subterfuge was necessary, is never explained.

Fortunately, once the plateau has been reached, the adventure is fast-paced and exciting, with plenty of action and adventure at every turn, involving both dinosaurs and a tribe of primitive men (who are condescendingly described as being relatively high up the evolutionary ladder – though obviously not nearly so high as the British explorers). The presentation of the prehistoric reptiles is certainly eccentric enough to be memorable: one two-legged predator is described as hopping like a kangaroo, which might not be scientifically accurate but which at least suggests a dynamic active form of life in keeping with our modern conception of dinosaurs (as opposed to the lethargic beasts often depicted in scientific theory of the past).

The Lost Worldis dated and flawed in some ways but remains entertaining as a sort of boy’s adventure story that can be enjoyed by adults, too. Malone’s motivation for joining the dangerous expedition is to impress a woman, but by the time he gets back she has left him for someone else. Instead of a heart-breaking moment, this is portrayed as a revelation of the fickle nature of women, prompting Malone to realize that the truly lasting and important bonds are between men who risk their lives side by side. It’s the perfect ending for a pre-adolescent boy too young to have developed an interest in girls yet.

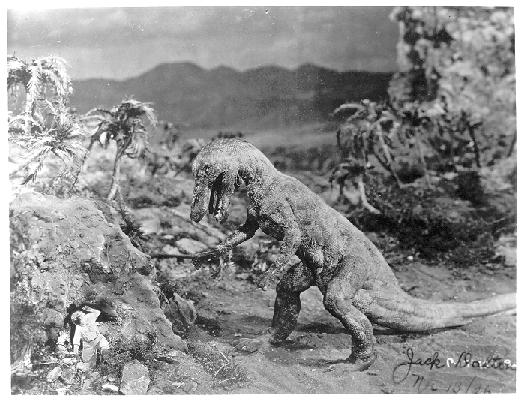

The first screen adaptation of Doyle’s novel is the 1925 silent film THE LOST WORLD, which is historically important as the first feature-length dinosaur movie. Although primitive by today’s standards, THE LOST WORLD is still entertaining as a showcase for Willis O’Brien’s old-fashioned stop-motion effects, and its story became the blue print for countless “lost world” films that would follow, including KING KONG (1933), which also featured O’Brien’s movie magic. The dinosaur action was greatly expanded for the film adaptation, with effects supervisor O’Brien filming scenes not in the novel or the screenplay. In effect the dinosaurs became the stars of the show, with the humans taking a back seat. This is especially true of the truncated version, the only one available for many decades, which deleted many of plot and character scenes that had originally been retained from the novel; restorations for laserdisc and DVD eventually revealed that the full-length film was reasonably faithful to its source, giving star Wallace Beery’s Professor Challenger at least a glimmer of the novel’s characterization.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s story had ended with Challenger bringing back a live specimen, a pterodactyl that escapes and flies home to its faraway land. One of the screenplay’s innovations was expanding this brief vignette into a third-act climax, replacing the relatively small flying reptile with an angry brontosaurs that breaks loose and runs amok in London. This sequence established what would become a cinematic tradition of unleashing prehistoric monsters on modern cities; the plot device has been recycled in everything from the various versions of KING KONG to Steven Spielberg’s film THE LOST WORLD: JURASSIC PARK. The JURASSIC PARK sequel was based on Michael Crichton’s novel The Lost World, which borrows not only its title but also an early scene from Doyle, in which a scientific lecture is interrupted by a renegade scientist who believes that dinosaurs have survived into the present day. One element that Crichton’s novel lacked was a T-Rex brought back to civilization; the addition of this sequence for the film underlines the lasting influence of the 1925 silent film.

Besides the homages and spin-offs, there have been several subsequent official adaptations of Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World. The First of these wasthe disappointing 1960 Irwin Allen production, which not only substituted Claude Rains for Wallace Beery as Professor Challenger but also, unfortunately, substituted made-up lizards for stop-motion dinosaurs. Michael Rennie (Klatuu in the 1951 DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL) is also on hand, and Jill St. John provides sex appeal, but not even the presence of Willis O’Brien on the effects team can compensate for the disappointment of the dinosaurs. (Ever the economical producer, producer Allen recycled this footage for the “Island of the Dinosaurs” episode of his television series, VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA.)

In 1992, disreputable producer Harry Allen Towers fashioned a surprisingly good version with John Rhys-Davies (LORD OF THE RINGS) as Professor Challenger. Despite phony-looking rubber-mechanical dinosaurs, the script and Rhys-Davies’ performance capture much of Challenger’s humor and temperament, which is often lost in other adaptations. David Warner (TIME AFTER TIME) is on hand in the thankless role of Challenger’s scientific colleague, but he brings his usual professionalism to the performance. The film and its follow up RETURN TO THE LOST WORLD received theatrical distribution in Europe but were sold as a two-part mini-series for American television and video. With a bigger budget for some really good special effects, this could have been a great movie.

After author Michael Crichton used the title The Lost World for his 1995 sequel to Jurassic Park, leading to the Steven Spielberg film two years later, it was perhaps inevitable that eager filmmakers would go back to Arthur Conan Doyle’s original book, which would allow them to fashion productions with the same title as a multi-million dollar summer blockbuster with no fear of legal action; after all, the novel they were adapting had prior claim to the title. Thus, we saw Patrick Bergin as a serious Professor Challenger in a competent but unremarkable version, directed by makeup effects man Bob Keen, which made its debut on U.S. television in 1998.

Shortly thereafter came the 1999 TV pilot, with the once-promising Richard Franklin (PSYCHO II) directing a no-name cast in a version of the tale that followed much of Doyle’s plot, with one notable change: instead of returning the characters to London as in the novel, the pilot ends with the expedition forced to remain in the lost world for the remainder of the series. As with the 1925 film, the television pilot upped the ante with the dinosaur footage; the script also added some romantic entanglements between the explorers and the natives (who are much more attractive than Doyle’s primitives), presumably so that the modern characters would not feel too badly about being trapped in the lost world for the three seasons that the series ran, until its demise in 2002. John Landis, one of the show’s executive producers, had previously hoped to mount a feature film version of THE LOST WORLD at Universal Pictures, with Richard Matheson scripting a faithful adaptation of Doyle’s novel, starring Sean Connery as Challenger, but Universal abandoned the project in favor of Spielberg’s JURASSIC PARK (1993).

More recently, the BBC presented a fairly faithful adaptation of THE LOST WORLD in 2001, which reached U.S. shores courtesy of A&E cable. In this version, Bob Hoskins takes over as Challenger, and JURASSIC PARK-style computer effects supply the dinosaurs. The premise behind this production seems to have been to do justice to Doyle, but the screenplay still tweaks many of the details, apparently in an attempt to render the production as a serious piece of science fiction, not merely a rousing adventure story. Hoskins is good (playing the professor as driven man whose personal life has been eclipsed by his work), and the film is decently entertaining, but it does overlook one excellent opportunity: Doyle’s book is dated by its Victorian view of dinosaurs (recollect that allosaurus-type predator chasing human prey by hopping like a kangaroo).

Today’s scientific view of dinosaurs is completely different, so it would have been interesting to portray Challenger and his colleagues starting off their old-fashioned paleontological theories and then radically revising after observing the living animals first-hand. Unfortunately, the script’s one nod in this direction is backwards: dialogue has the Victorian scientists expecting to see an Iguanodon walk upright; when they encounter one, it is on all fours. The truth is the complete reverse: scientists from Challenger’s era would have expected to see an Iguanodon on all fours, but later research revised the image of the creature as bi-pedal.

Of course, Conan Doyle will always be remembered as the creator of Sherlock Holmes – a fact that would not have pleased him. If he is looking down on us from somewhere in literary heaven, he is probably grateful to see that at least one other of his literary efforts continues to inspire and influence filmmakers today. No doubt modern day dinosaur films will continue to flourish, thanks to the ever-improving innovations in the special effects field, but Doyle’s original novel really is a literary work worth reading for its own fine qualities, and as far as professor-scientist-explorer characters go, Professor Challenger stands head-and-shoulders above his competitors in the field.