Essential vewing, but not another masteripece, from from AKIRA-creator Katsuhiro Otomo

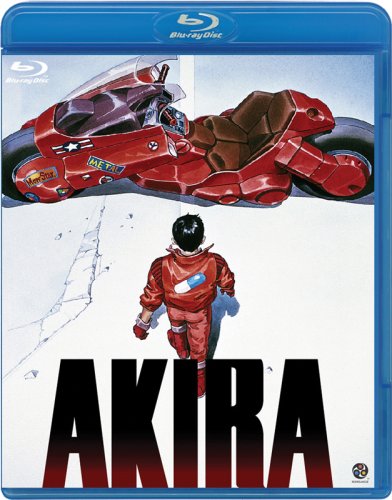

Katsuhiro Otomo’s STEAMBOY, his first feature-length anime since 1988’s AKIRA, is another excellent piece of cinematic science fiction, filled with the dazzling animation, beautiful backgrounds, and absolutely awe-inspiring action scenes. It is also a lesson in how the march of time can affect viewer reaction to an artist. When AKIRA came out, it was a groundbreaking piece of work that outdistanced both Japanese and American animation in terms of ambition and style. STEAMBOY, on the other hand, is a remarkable achievement, but it does not outclass contemporary efforts like GHOST IN THE SHELL: INNOCENCE.

Katsuhiro Otomo’s STEAMBOY, his first feature-length anime since 1988’s AKIRA, is another excellent piece of cinematic science fiction, filled with the dazzling animation, beautiful backgrounds, and absolutely awe-inspiring action scenes. It is also a lesson in how the march of time can affect viewer reaction to an artist. When AKIRA came out, it was a groundbreaking piece of work that outdistanced both Japanese and American animation in terms of ambition and style. STEAMBOY, on the other hand, is a remarkable achievement, but it does not outclass contemporary efforts like GHOST IN THE SHELL: INNOCENCE.

Set in the Victorian era (1866, to be precise), the mildly convoluted story begins with an industrial accident in Alaska, presided over by the father-son team of Lloyd and Edward Steam, with the elder Lloyd insisting on going full bore while the younger Edward is injured trying to prevent disaster. The action shifts to Manchester, where grandson Ray Steam receives a package from Lloyd containing a “steamball.” Ray is instructed to keep the device out of the hands of the O’Hara Foundation, an American entrepreneurial company that employed both Lloyd and Edward, but both he and his grandfather are kidnapped by the company. Ray is surprised to find his father, now disfigured into a combination of the Phantom of the Opera and the Frankenstein Monster, still working for O’Hara, which is presided over by the founder’s obnoxious granddaughter, Scarlett. The steamball, it turns out, is a powerful energy source, filled with a mysterious liquid of great “purity” that has been highly condensed and pressurized. Edward wants to harness this new energy source to push humanity into the next century. Unfortunately, the O’Hara foundation earns its money by war profiteering, and Lloyd fears the consequences of leaving the steamball in their hands. In the final act, the O’Hara demonstrates their newest weaponry (in an amusingly absurd plot development) by launching a small-scale war at an Exhibition in London, destroying large parts of the city in the process. Ray, who has been pulled back and forth in the conflict between his father and grandfather, manages to improvise a flying device and help prevent an even greater disaster, rescuing Scarlett in the process.

STEAMBOY has rightfully been reviewed as a film filled with visual grandeur that falters in the area of narrative development. The story begins with not one but two machinery-gone-haywire scenes, first with Lloyd and Edward, then with Ray. Then the story shifts into a nice Alfred Hitchcock pastiche, with Ray as the naive innocent thrust into the middle of a pursuit for a valuable object sought by rival factions. There is some interesting dramatic conflict, with Ray torn between his father and his grandfather’s views of the progress of science, but the effect is somewhat undermined by Lloyd’s unacknowledged change of heart: when we first see him, he is the one willing to risk everything for progress; apparently, the accident changed his mind, but he never says so. The story slows down in the middle section, with the debates about the virtues and perils of science sounding like old-hat lectures (somewhat reminiscent of, though not nearly so bizarre as, the “amoeba” speech from AKIRA). Thankfully, the film delivers a spectacular climax that features Edward’s crowning glory, “Steam Tower,” a battleship size structure resembling a small city, literally taking flight over London.

STEAMBOY’s success is based mostly on its visual achievement, with numerous Jules Verne-inspired gadgets (flying machines, submarines, etc) showcased in breathtaking fashion. Early on there is a wonderful chase scene involving Ray’s steam-powered unicycle, a steam-powered tractor, and a train, which ends with a dirigible grapping one of the train cars and nearly crashing into Victoria Station. The battle scenes are exciting, without being as graphically violent as anything in AKIRA.

The film’s message may be heavy-handed, but it is delivered with a sort of over-the-top sincerity: Lloyd thinks his son Edward has turned evil because he has sold his soul to “capitalists” who make money from weapons; Edward’s English counterpart, Robert Stephenson, also wants to get his hands on the steamball, but for the sake of protecting the nation, not for making money. As is often the case in Japanese films, the conflict seems muddled to Western viewers because neither side is presented as wholly good or evil; rather they are competing philosophies, and the protagonist (in this case Ray) sides with one or the other depending on how it advances his personal agenda, in some cases flipping back and for the between the two (see PRINCESS MONONOKE for comparison).

The one element that prevents STEAMBOY from achieving critical mass is the characterizations. Otomo’s futuristic punks in AKIRA may not have been ideal role models, but they were interesting, in a cyberpunk kind of way. The two young leads in STEAMBOY come from a separate tradition of adorable, youthful protagonists, such as those seen in Hayao Miyazaki’s LAPUTA, CASTLE IN THE SKY. The difference is that Miyazaki actually manages to charm us with his cute couple; Otomo does not. Much of the problem rests with Scarlett – little more than a spoiled brat (basically, a caricature of the ugly American) who periodically beats her pet dog for no particular reason. Her obnoxious quality at times approaches camp levels, leading viewers to expect a comeuppance worthy of her behavior – which, sadly, never really arrives. (The closest we get is her rude awakening when she gets a first-hand glimpse at the carnage wrought by the weapons her foundation manufactures.)

Nevertheless, STEAMBOY remains a must-see for anime fans and for those interested in seeing a wonderfully exciting artistic vision put up on the screen with grandeur and beauty in abundance. Rather like LEAGUE OF EXTRAORDINARY GENTLEMEN and SKY CAPTAIN AND THE WORLD OF TOMORROW, Otomo’s new film aims to create a futuristic alternate reality out of the past. Unlike those previous films, STEAMBOY hits the target with a bulls-eye, filling the screen with eye-popping entertainment that is carefully calibrated to astound without collapsing under the weight of its own excess. It may not be another AKIRA; it may not even be another masterpiece; but it is essential viewing.

TRIVIA

The obnoxious female lead is named Scarlett, and she just happens to be the “granddaughter of the founder of the O’Hara Foundation.” Although no character addresses her by her full name, this would seem to make her “Scarlett O’Hara.”

A montage of still images over the closing credits provides glimpses of the future adventures of Steamboy (i.e., Ray, looking a lot like Rocket Boy, with a flying jetpack on his back), implying that the film is intended to launch a franchise. On the director’s cut DVD, this montage can be viewed without the credits, providing a better view of the images.

DUBBING

In the United States, STEAMBOY was released in two versions: a subtitled directors cut and a re-edited cut (approximately fifteen minutes shorter) that was dubbed into English (featuring the voices of Anna Paquin, Patrick Stewart, Alfred Moline, etc.). The Director’s Cut DVD presents both the English- and Japanese-language versions in unedited form.

The re-voiced dialogue effectively captures dialects appropriate for the Victorian England setting (with the lead characters coming from Manchester, the soundtrack inevitably suggests — to American ears, at least — the Beatles in A HARD DAY�S NIGHT). This may be one of the few times that dubbing actually improved a film, because the new soundtrack is better suited to the story being told, in terms of accents and phrasing.

In fact, the high-toned anti-war, pro-science rhetoric actually sounds better in the English version. The dubbing improves over the subtitles by fashioning dialogue that is more dense and flowery avoiding the too-blunt, telegraphic approach of the written words. For example, upon seeing a vast room of new inventions, the lead character’s “Golly!” has been expanded to “This is incredible!” Somewhat less effectively, “Steam Tower” is changed to “Steam Castle,” even though the structure barely resembles a castle.

DVD DETAILS

The Director’s Cut DVD is a bit of a disappointment. Although the film itself is worth seeing, its presentation on disc does not do it justice. Still, the chance to see the uncut version with the English-language dialogue makes it worthwhile, in spite of the shortcomings.

The first problem is the image quality: the film looks slightly washed out, with low-contrast and dull colors. Curiously, the disc provides a gauge by which to judge the picture quality: the clips from the film shown in the bonus features are all bright and sharp and vibrant.

The Bonus Features consists of a handful of Featurettes; Animation Onionskins; and Production Drawings. (There are also trailers for unrelated films, like FINAL FANTASY VII and THE CAVE.)

The first featurette “Re-Voicing Steamboy” includes an assembly of interviews, mostly with the three lead voice actors: Anna Paquin (Ray “Steamboy”), Patrick Stewart (Dr. Lloyd Steam), and Alfred Molina (Dr. Edward Steam). Mostly they talk about the familiarity (or lack thereof) with Japanese animation and about their technical difficulties of creating a vocal performance to a film that has already been created. Lacking specifics, the featurette tend to bog down in dull generalities; about the most interesting tidbit is learning that that the sound director for the original Japanese-language version was involved with the dubbing process.

The interview with writer-director Katsuhiro Otomo tells us that he spent ten years on the film: three years planning and seven years of production work, but that is about all you learn of significance. Unfortunately, the auteur’s Japanese comments are translated into a voice-over audio instead of rendered in subtitles – a bad, distracting idea.

The longest featurette is a “three-screen” presentation created to promote the film before its release: the top half of the frame is divided into two small sections, while the bottom half provides a “widescreen” image. Beginning with comparisons of live-action reference footage, temporary renderings, and final animation, the featurette soon moves into a series of subtitled interviews with Otomo and the animators (who are not identified by name). A few interesting details are parceled out very slowly, and for some reason almost everyone involved seems to be having nasal problems – count how many times they scratch and wipe their noses on screen!

The “Animation Onionskins” are basically glimpses of unfinished animation, showing how scenes were originally rendered on the computer, with details gradually being added.

The Production Drawings segment features a nice montage of artwork set to music from the film. To some extent, the title hardly does justice to the images: much of what is seen is far more than a mere drawing, looking more like fully rendered paintings worthy of hanging in a museum.

The DVD Gift Set includes all those features, plus these bonus materials: 10 Steamboy Collectible Postcards; a 22-page manga (i.e., comic book); a 166-page booklet containing character designs, mecha designs, and selected storyboard sequences.

STEAMBOY (2004). Directed by Katsuhiro Otomo. Written by Katsuhiro Otomo & Sadayuki Morai. Voices (Japanese): Amne Suzuki, Masane Tsukayama, Katsuo Nakamura. Voices (English): Anna Paquin, Patrick Stewart, Alfred Molina.

Copyright 2005 Steve Biodrowski

Katsuhiro Otomo’s STEAMBOY, his first feature-length anime since 1988’s AKIRA, is another excellent piece of cinematic science fiction, filled with the dazzling animation, beautiful backgrounds, and absolutely awe-inspiring action scenes. It is also a lesson in how the march of time can affect viewer reaction to an artist. When AKIRA came out, it was a groundbreaking piece of work that outdistanced both Japanese and American animation in terms of ambition and style. STEAMBOY, on the other hand, is a remarkable achievement, but it does not outclass contemporary efforts like GHOST IN THE SHELL: INNOCENCE.

Katsuhiro Otomo’s STEAMBOY, his first feature-length anime since 1988’s AKIRA, is another excellent piece of cinematic science fiction, filled with the dazzling animation, beautiful backgrounds, and absolutely awe-inspiring action scenes. It is also a lesson in how the march of time can affect viewer reaction to an artist. When AKIRA came out, it was a groundbreaking piece of work that outdistanced both Japanese and American animation in terms of ambition and style. STEAMBOY, on the other hand, is a remarkable achievement, but it does not outclass contemporary efforts like GHOST IN THE SHELL: INNOCENCE.