[EDITOR’S NOTE: This article originally appeared on the Hollywood Gothique website on June 10, 2005.]

The premier of HOWL’S MOVING CASTLE, shown in the English-dubbed version at El Capitan Theatre on Thursday, June 9, 2005, was a rousing experience for fans of animation master Hayao Miyazaki. Unfortunately, the Japanese writer-director was not on the panel discussing the film before the screening, but there was some informative and amusing commentary from moderator Charles Solomon (an animation expert), actresses Jean Simmons and Emily Mortimer, the screenwriting team of Cindy and Donald Hewitt (who provided the English-language dialogue), and a handful of Disney-Pixar people who supervised the dubbing of the film for American audiences.

Some of the interesting tidbits:

The lead character of Sophie, a young woman who is turned into a ninety-year-old crone by a witch’s curse, was voiced by a single actress in the Japanese version, but the American audio track splits the character into “young” and “old” voices, the first by Mortimer, the second by veteran actress Simmons. Simmons was chosen because she could convey not just a mature-sounding voice but a sense of youthful vigor masked by visible age. Mortimer was selected because she could sound like a younger version of Simmons (specifically, the filmmakers listened to Simmons’ old films like SPARTACUS).

The role of the Witch of the Waste was given to Lauren Bacall (whose career stretches all the way back to classic 1940s films like TO HAVE AND HAVE NOT). The filmmakers were worried that the actress, once an icon of glamour, would be insulted by the choice of character, warning her, “This character is a bit despicable.” Bacall’s response: “Darling, I was born to play despicable!”

Christian Bale landed the role of the ambivalent wizard Howl after his agent supplied a voice clip of the actor from BATMAN BEGINS. The casting is appropriate, since Howl (like Bruce Wayne) leads a bit of a double-life, turning into a winged bird-like monster at night.

After completing the dub, the film was screened in New York, with Miyazaki in attendance. To the surprise of the American filmmakers, Miyazaki sat through the dubbed version (he has a reputation for walking out in the past). Afterwards, the Americans asked Miyazaki’s translator to inquire whether he had liked the film. She warned them not to ask unless they wanted to hear the truth “because he’ll tell you, so if you don’t want to know, don’t ask.” The Americans asked; the translator translated; Miyazaki bowed and told them “good job.”

Jean Simmons called the dubbing process a “learning experience.” Unlike American animation, which records voices first and then animates the characters to match, Japanese anime is filmed first and dubbed later. (Perhaps jokingly, Miyazaki told the American dubbers that he uses this method so that he has complete control over how the actors read their lines). The trick, of course, is to get in character while standing in a sound booth watching through a window as the film unspool on a screen in a black room next door.

Under the circumstances, dialogue is difficult enough; almost as tricky is conveying the inarticulate part of the performance — for example, the strain Old Sophie endures when climbing a mountain of stairs while hauling an asthmatic dog along with her. “I never huffed and puffed so much in my life!” said Simmons.

Mortimer agreed, laughing, “It was almost like making a porn film — there was so much gasping and panting!”

By this time, the children in the audience were getting a bit antsy for the beginning of the film. Not surprisingly, in a city as diverse as Los Angeles, this Japanese family-oriented film attracted a fair number of Asian-Americans with young children. (The little boy a few seats down from me was a dead ringer for Toshio from THE GRUDGE; I kept looking around for his ghostly mother Kayako to materialize — the anticipation of which lent the screening an edge it might not otherwise have had.)

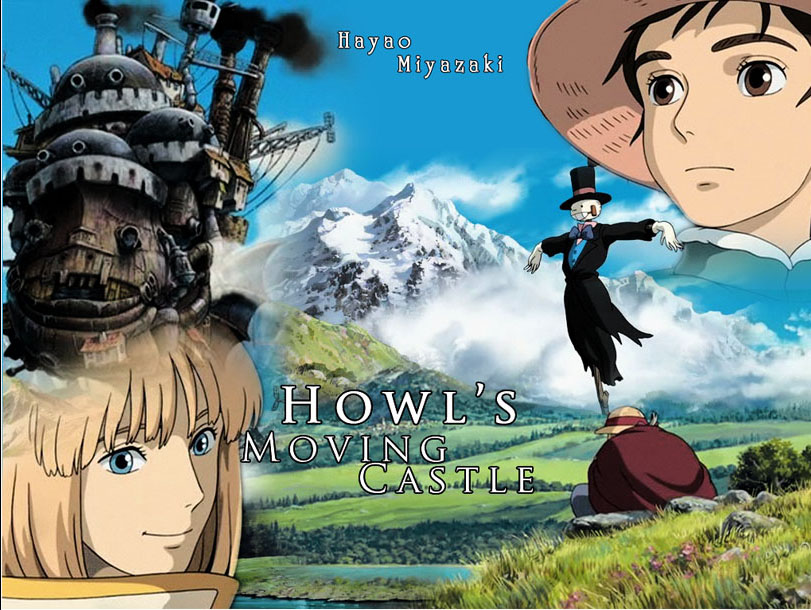

The film that unspooled was fairly typical Miyazaki, in all its strengths and weaknesses: it’s beautiful and filled with numerous heart-felt story elements and themes (about greed, cowardice, war, etc), but as is often the case, how these elements connect on a plot level is not as important as how beautifully they are rendered on screen. The film is filled with amusing characters and bizarre images (like a legless scarecrow hopping about on its wooden post), but you’d be hard-pressed to explain the logic of the film’s happy ending (at least three curses are lifted in the last few minutes, but the details of how this is achieved are glossed over).

Ultimately, the film is not as impressive as Miyazaki’s ambitious PRINCESS MONONOKE, but it captures the pastoral beauty and charm that we have come to expect from the creator of LAPUTA: CASTLE IN THE SKY and MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO. That’s more than enough to make it worth seeing.

Copyright 2005 Steve Biodrowski