Unlike the Energizer Bunny, the new Godzilla is a windup toy that runs down – or, if you’ll pardon the mixed metaphor, runs out of radioactive steam.

Godzilla roars again, but the sound has been fed through a broken ring modulator, resulting in a distorted signal. This is highly unfortunate, since the new film SHIN GODZILLA (Shin Gojira in its original Japanese – which translates to “Godzilla’s Resurgence”), bristles with promise in the form of satirical jabs at governmental bureaucracy and clever winks at the history of the character (whose dual name “Gojira/Godzilla” forms the basis of an amusing joke at the expense of the U.S.A.). The movie is funny without being an overt comedy, and the humor never undermines the titular behemoth. The filmmakers have other methods for doing that.

Godzilla roars again, but the sound has been fed through a broken ring modulator, resulting in a distorted signal. This is highly unfortunate, since the new film SHIN GODZILLA (Shin Gojira in its original Japanese – which translates to “Godzilla’s Resurgence”), bristles with promise in the form of satirical jabs at governmental bureaucracy and clever winks at the history of the character (whose dual name “Gojira/Godzilla” forms the basis of an amusing joke at the expense of the U.S.A.). The movie is funny without being an overt comedy, and the humor never undermines the titular behemoth. The filmmakers have other methods for doing that.

Shin Godzilla gets off to an intriguing start (reminiscent of Godzilla 1985) when the coast guard encounters a mysterious unmanned vessel, which is capsized by some unseen force before it can by towed to shore; moments later, some kind of impact causes a leak in an undersea tunnel. A series of rapid-fire shots conveys the government’s response: the irony of the editing is that the response itself is anything but rapid, as officials hem and haw, wrangling over the nature of the threat and which department should handle it. The result is an amusing satire of of the Japanese government’s decision-making process, depicted as hopeless mired by concerns of form (the ministers keep ducking back into the Prime Minister’s office because conversations in the main room are on the record, and not everyone feels comfortable with what needs to be said out loud). It’s not quite Dr. Strangelove, but it’s fun for a while.

The film establishes an approach not dissimilar from that seen in some anime series, revealing character names and job descriptions in subtitles. More than just a technique to eliminate awkward exposition, this cinematic style sets the tone of the film, which is as lean as the 5%-fat beef one buys in the supermarket: this is a movie totally focused on process; characters exist only in terms of their job functions, and all conflicts relate to the main objective. There is no time wasted on building characters with humanizing domestic scenes or personal conflicts; only one seems to have a family member – who is, pointedly, rendered completely faceless.

As energizing as this approach is, it cannot sustain an entire movie (unless rendered by some kind of genius). At some point the film has to settle into a grove and get down to the actual business of telling its story by depicting the threat of Godzilla. Ironically, in this regard, Shin Godzilla stumbles about as awkwardly as its initial depiction of Godzilla. When the radioactive beast first reveals itself, it looks like an overgrown polliwog, hunched over and almost slithering on its belly (an unpleasant reminder of Emmerich and Devlin’s 1998 Godzilla). The waving moments of its head suggest a Chinese dragon at a parade; one expects to see humans underneath, manipulating the creature with rods. Even worse, its unblinking eyes look like giant buttons; probably intended to suggest a mutated creature, they are too big, suggesting a cute anime character instead of a destructive menace.

Fortunately, Godzilla soon mutates into an upright creature, but he never fully becomes the familiar icon. He always looks a half-formed abomination with vaguely Godzilla-esque characteristics. This might have been an acceptable approach, except that it contradicts one thrust of the screenplay: as in the 2014 Godzilla, this creature is supposed to provoke the awe one associates with a deity (we’re told the “Gojira” means “God Incarnate”). That simply cannot work when the mangy creature’s only claim to god-like status is size; it needs to look awesome in order to be awesome.

It’s a little hard to tell whether this problem is completely one of design or partly attributable to the effects artists. Clearly there is an attempt to distort perspective in order to convey Godzilla’s size as seen from humans at ground level, but as often as not this simply makes the beast seem malformed, especially in long shots, where the tail seems almost larger than the body.

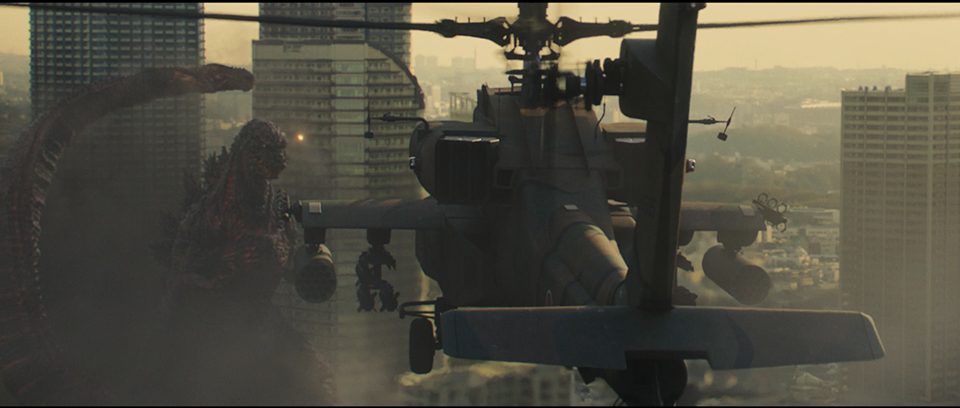

Excellent CGI composite work replaces old-school miniatures.

Unfortunately, the problem is not only cosmetic; it goes beneath the skin. The initially intriguing attempts to have the human characters analyze this new life form (despite the “Resurgence” in the title, the film treats Godzilla as something new) come to nothing. Many metaphoric cans of worms are opened, but the dissection is left unfinished, resulting in a depiction of Godzilla that is more non-entity than powerful enigma.

There is a nice attempt to show some limits to the beast, whose initial foray onto land is cut short because of a need to regulate its body temperature by returning to the water. Later, it becomes apparent that Godzilla (who true to form feeds off nuclear fuel) needs to recharge after expending his energy. This affords an opportunity for the characters to develop a strategy, but it also subverts the films’ central threat, rendering Godzilla as little more than a big windup toy that frequently runs down – just long enough to allow his lilliputian adversaries to get the jump on him. (I’m not using the windup toy metaphor casually: Godzilla does not curl up to sleep after expending nuclear energy; the beast almost literally stops in mid-stride, tail poised in the air, exactly like a mechanical device whose spring has wound down.)

Quibbles about the creature’s depiction aside, Shin Godzilla is engrossing for its first two-thirds, building to an amazing confrontation between the monster and combined Japanese-U.S. forces, which results in an orgy of devastation that is spectacular and haunting in equal measures. Unfortunately, the third act is unable to top this mid-movie climax, as it focuses on one of the least exciting plans ever devised to defeat Godzilla, which consists of firetruck-like vehicles using hoses to feed a “de-coagulate” into the dormant monster’s mouth; unintentionally funny, the scene suggests that Godzilla is having dental work.

The strategy results in a non-ending that literally stops the clock without resolving the story. The anti-climax literally feels like a fake-out: the audience expects the characters to breath a sigh of relief just before – surprise! – Godzilla springs back to life and they have to figure out how to really kill the beast. Instead, the film simply stops, leaving an opening for a sequel so wide that Godzilla itself could have fallen into it (SPOILER: a final shot of Godzilla’s tail shows that a little asexual reproduction is about to take place, spawning new Godzillas – another unfortunate reminder of the 1998 film. END SPOILER) In the end, Shin Godzilla – rather like its title character – runs out of (radioactive) steam.

Which is sad, because there is so much that is good, great, and even amazing about Shin Godzilla. The initial scenes have a nice contemporary feel designed to make the concept work as something more than a nostalgia piece (despite the frequent soundtrack excerpts from past films). There has never been a Godzilla film that wrestled so carefully and believably with the questions of collateral damage and rules of engagement (more on which later). And in what could have been a sop to younger viewer but turns out to be an encouraging statement about human cooperation, the success against Godzilla is rendered by a younger generation of government employees and experts who pointedly forge a “flat” organization, without a traditional hierarchical structure, where everyone is invited to speak up and contribute, without having to cut through fifteen layers of red tape.

Shin Gojira does not lack big-scale monster action. The old miniatures have been put in mothballs, replaced by computer-generated imagery that renders destruction spectacular detail; even if Godzilla looks a bit lumpy, the tanks and attack helicopters are convincing, and the coordinated attack on their target is one of the most spectacular scenes of its kind ever committed to what passes for celluloid these days. In an attempt to avoid citywide destruction as much as possible, the human adversaries employ a strategy of gradual escalation, starting with machine guns, then missiles, then canons, and finally culminating in a B-2 bombing run by cooperating American forces, which finally breaks the skin and sheds some blood – just enough to make the monster retaliate, spewing plumes of purple radioactive breath and shooting energy beams out of its dorsal spines in a spectacular barrage of special effects.

This display of near invulnerability ultimately exposes a fundamental problem with the script, which fails where previous Godzilla films succeeded: even when they were a tad silly, the Toho movies of the 1990s and the 2000s did a good job of talking out of both sides of the mouth – depicting Godzilla as a threat while simultaneously suggesting that he might be less of a threat than his current opponent (be it King Ghidorah or whatever). After going the extra mile to depict Godzilla as a force that threatens the entire world – a form of life superior to humanity, which will probably lead to our extinction unless destroyed – Shin Godzilla goes out of its way to portray the umbrage of its Japanese characters when the U.N. (led by the U.S. naturally) decides that the monster needs to be nuked.

You may remember the scene in The 7 Samurai in which a decision was made to sacrifice a few homes in order save the village under attack, but that’s not what Shin Godzilla has in mind: the filmmakers want us to see the decision as an example of a trigger-happy U.S. eager to nuke Japan again (partly because, for reasons too garbled to be worth repeating, the U.S. has a vested interest in Godzilla that it would like to cover up). Now, this is a perfectly valid plot complication for a Godzilla movie – but not when the script has gone so far to put humanity’s survival on the line that nuking Godzilla seems like a necessary (though tragically regrettable) move.

This confusion stems from the nationalistic tone of the Shin Godzilla, which expands on themes visible in Japan’s kaiju eiga genre going back the past two decades – not only Toho’s Godzilla series but also Daiei Film’s rival Gamera franchise. If the movies are to be believed, Japan is tired of depending on foreign power for protection; they want to rebuild their military might and, more importantly, loosen the restrictions on using it. Most of all, they don’t want the U.S. dictating policy. Well, fine and dandy, I say, as long as they realize that this message resonates well within the context of a movie about a giant monster attacking heavily populated urban centers but somewhat less so in a real world where actual violence and warfare is on the decline.

Conceptual confusion aside, Shin Gojira is a slickly made product, with good tech credits (even if some of the animation is less than convincing). The Japanese cast provide appropriate sincerity and gravitas; though the characters are not rendered in complex detail, the performers come across as focused on the overwhelming task at hand, rather than one-note.

The American characters are another matter. In keeping with Toho tradition, these roles seem to have been cast with amateurs. Director Hideako Anno disguises this to some extent by framing the actors in long shots or having them talk with their backs turned while exiting a room. This works for a while but ultimately becomes funny when the technique becomes too obvious: during a dialogue between Kayoko Ann Patterson (Satomi Ishihara) and her American father, the elder Patterson is seen only as hands and arms, the camera pointing every direction except his face. Hilarity ensues.

Which brings us to the issue of Ishihara’s performance. Her character, a liaison to Japan, is supposed to be an American with a Japanese grandmother, but her awkwardly delivered English dialogue is clearly spoken by someone who did not grow up in the U.S. As if to underline the shortcoming, other Japanese characters do a much better job delivering English while coordinating their anti-Godzilla efforts with American counterparts. Presumably, Japanese audiences were little concerned with this, but it is rather blatant to U.S. viewers.

We have to give the filmmakers credit for teaching the old monster some new tricks; even if their efforts are only partially successful, two-thirds of a great movie is not bad. With its weird mutant, Shin Godzilla shares a certain affinity with the misguided 1998 Americanization of Godzilla: both films seem to have been made by people who did not want to make a Godzilla movie, so they tried to make something else and call it Godzilla. Rolland Emmerich and Dean Devil gave us a JURASSIC PARK ripoff. Hideako Anno and Shinji Higuchi give us a twisted variation on Attack on Titan, which goes so far as to hint that Godzilla is not merely the product of accidental nuclear contamination but perhaps a deliberate experiment by a scientist (“Goro Maki,” named after a character in Godzilla 1985) angry over the demise of his wife. In fact, the mysterious disappearance of Maki, immediately before Godzilla’s appearance, even leaves open the possibility that Maki may be Godzilla* – one of many unresolved plot points that will probably be explored in sequels. It’s just one more way that Shin Gojira falls flat at the end, too tired, apparently, to bother finishing its story, instead simply stopping to resume another day. Hopefully, like Godzilla, any follow-up will be fully recharged – and will allow its creature to mutate into a Godzilla that deserves the “god” in his name.

Note: This review has been updated after a second viewing of the film.

Footnote:

- In the Attack on Titan anime series, the cannibalistic giants are eventually revealed to be humans who expand to titanic proportions. There is also a scientist who disappears without explanation; presumably future seasons will tell us he had something to do with the creation of the Titans. To be fair, this plot element in Shin Gojira also echoes Warner Brothers Godzilla (2014), in which the prehistoric alpha-predator appears only after the demise of Joe Brody (Bryan Cranston), suggesting that his spirit is somehow imbued in the beast.

[serialposts]

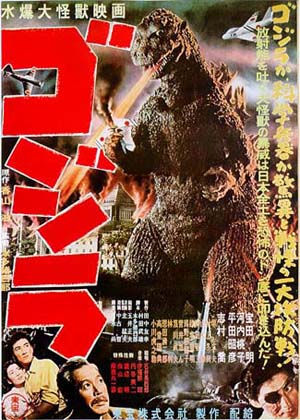

To the average American audience, the original Godzilla is a cheesy man-in-a-suit monster smashing cardboard buildings and stomping matchbox-size cars – something so bad that atrocious computer-generated lizard in 1998’s American-made GODZILLA is actually perceived as an improvement. Science fiction fans may be a bit kinder in their assessment, acknowledging that Godzilla’s debut film is much better than the sequels that followed, but even they tend to rank the Japanese giant well below his American counterparts. In Japan, however, the original 1954 GODZILLA is considered to be a classic on par with KING KONG (1933).

To the average American audience, the original Godzilla is a cheesy man-in-a-suit monster smashing cardboard buildings and stomping matchbox-size cars – something so bad that atrocious computer-generated lizard in 1998’s American-made GODZILLA is actually perceived as an improvement. Science fiction fans may be a bit kinder in their assessment, acknowledging that Godzilla’s debut film is much better than the sequels that followed, but even they tend to rank the Japanese giant well below his American counterparts. In Japan, however, the original 1954 GODZILLA is considered to be a classic on par with KING KONG (1933).

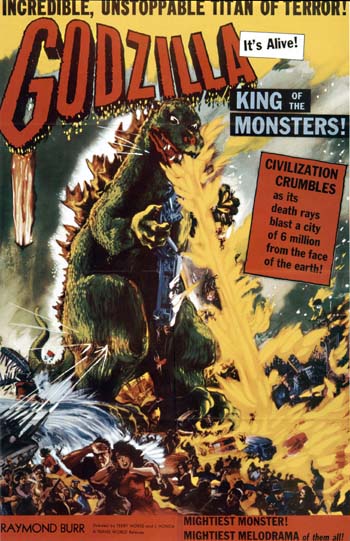

Disc Two contains GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS (divided into a meager 9 chapter stops), a U.S. trailer, and another audio commentary by Ryfle and Godziszewski.

Disc Two contains GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS (divided into a meager 9 chapter stops), a U.S. trailer, and another audio commentary by Ryfle and Godziszewski.