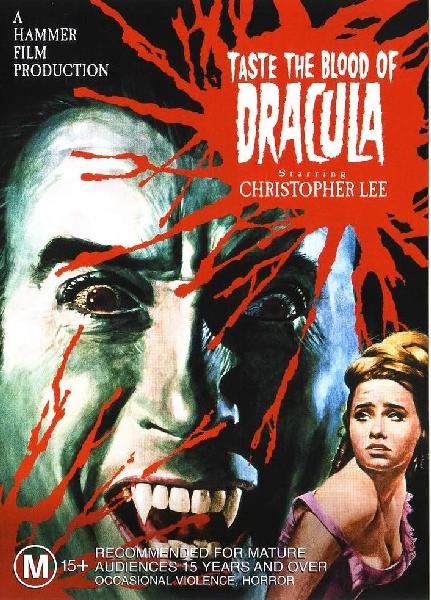

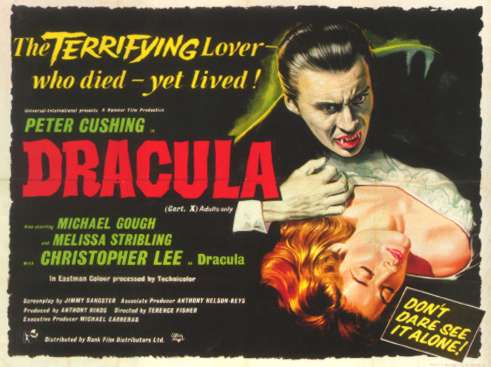

This, the fourth Hammer horror film starring Christopher Lee as Count Dracula, is the last solid effort in the franchise. The film charts some interesting thematic territory and features a number of interesting ideas. Unfortunately, the script by John Elder (the pen name of Anthony Hinds) does not weave all of these ideas together into a satisfying whole, and the direction by Peter Sasdy, while competent, lacks the solid sophistication of Terence Fisher (Horror of Dracula) and/or the visual flair of Freddie Francis (Dracula Has Risen from the Grave). The result is fascinating but frustrating — probably the most ambitious of Hammer’s Dracula sequels, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA unravels when its ambitions are torn apart by the obligatory genre conventions.

This, the fourth Hammer horror film starring Christopher Lee as Count Dracula, is the last solid effort in the franchise. The film charts some interesting thematic territory and features a number of interesting ideas. Unfortunately, the script by John Elder (the pen name of Anthony Hinds) does not weave all of these ideas together into a satisfying whole, and the direction by Peter Sasdy, while competent, lacks the solid sophistication of Terence Fisher (Horror of Dracula) and/or the visual flair of Freddie Francis (Dracula Has Risen from the Grave). The result is fascinating but frustrating — probably the most ambitious of Hammer’s Dracula sequels, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA unravels when its ambitions are torn apart by the obligatory genre conventions.

The film begins with Weller (Roy Kinnear), an English merchant who is tossed out of a coach while traveling through Europe. He stumbles through a forest just in time to see the demise of Dracula (including footage reprised from Dracula Has Risen from the Grave). The story shifts to England, where a trio of hypocritical English gentlemen maintain respectable facades in their community while periodically enjoying a trip to the brothels in a seedy quarter of London. Eager for new thrills, they hook up with Lord Courtley (Ralph Bates), a young, disinherited Satanist who offers to perform a ceremony for them if they will purchase the necessary ingredients — namely, the cloak, clasp and dried blood of Dracula, which Weller brought back with him. During the ceremony, which takes place in an abandoned church, the three thrill-seekers kill Courtley in a panic after he mixes his blood with Dracula’s and drinks the concoction. Later, Courtley’s dead body mutates into Dracula, who vows to kill the men who destroyed his servant. Meanwhile, the various children of the three Englishmen have been interacting and falling in love, much to their fathers’ disapproval. One by one, the Count puts the young adults under his spell and turns them against their fathers, who die gruesome deaths at the hands of their sons or daughters. After all three are dead, young Paul (Anthony Corlan) manages to rescue his girlfriend Alice (Linda Hayden), who had been Dracula’s chief accomplice: Paul restores a handful of sacred objects to the abandoned church, which Dracula is using as his lair, and the Count seems to go insane, imagining the church fully restored, the power of Good overwhelming him until he falls onto the alter and shrivels away.

Thematically, TASTE OF THE BLOOD OF DRACULA is intriguing — a sort of broadside attack on Victorian hypocrisy. The film evinces an almost radical agenda, in which we are openly invited to identify with the children as they turn the tables and slaughter their fathers, who have unreasonably repressed them. Dracula is barely a character in the film; rather, he is a catalyst — the missing ingredient that inspires the spineless, almost bloodless youngsters to rise up against their oppressors. One could easily read the result as a sort of Freudian-Marxist manifesto about overthrowing both sexual and social repression.

The film fares less well on a purely narrative level. For example, one of the three thrill-seekers conveniently knows how to kill vampires — because somebody has to, and there is no Van Helsing character around. The script also expects us to sympathize with this character, even though he was willing to sell his soul the Devil in Courtley’s ceremony and also got away with murder.

Even more important: From the external evidence, it is rather obvious that the script was originally written with Lord Courtley as the central character, who is killed and then returns from the dead to extract vengeance. Adding Dracula into the mix was an awkward afterthought — a reluctant bow to the obvious commercial consideration that far fewer ticket buyers would flock to see TASTE THE BLOOD OF COURTLEY. Consequently, the Count has little to do but lurk in the shadows while his young minions do most of the dirty work, and Christopher Lee’s few lines of dialogue are rather bald-faced efforts to explain the Count’s motivations (“They have destroyed my servant. They will be destroyed,” he announces to the camera immediately after coming back to life.)

The result is one of Lee’s weaker performances in the role of Dracula. He performs the obligatory actions, hypnotizing and biting his victims, with his usual overpowering screen presence, but he cannot make the character anything more than a spook in a graveyard. The film probably gives him the least screen time of any in the Hammer series, sometimes even relying on a stunt double or a glimpse of a cloak to suggest his presence, instead of giving the actor a real scene to play.

Instead, the emphasis is on the young leads. The film is clearly designed to appeal to younger viewers. All of the adults are either hypocrite or pathetic or (in the case of the police) willfully negligent. The burden of solving the situation falls upon Paul, whose boyish good looks and curly brown hair seem consciously devised to suggest Paul McCartney to the target audience of teenagers. Corlan does a good job in the role, but in general the film succumbs to the pitfall inherent in the gambit the script plays: by making the long-repressed youths so helpless in the early scenes, it renders them uninteresting and unlikable; the only kick we get out of them is seeing them finally turn the tables against the oldsters.

In fact, the film does such a good job of making us hate the fathers and root for their downfall, that the ultimate Good-triumphing-over-Evil conclusion seems tacked on from another movie. The script overturns traditional definitions of Good and Evil by making the apparently respectable Englishmen into hypocrites and murderers. The movie more or less endorses their destruction at the hands of their children. Yet Alice, the most complicit in the retribution, is let off the hook in favor of placing all the blame on Dracula — who, in a sense, merely liberated her from an unpleasant situation by giving her the nerve to do what she wanted — but dared not — do on her own.

Despite the erratic storytelling, the usual Hammer virtues are on display. The sets are atmospheric. James Bernard provides one of his best scores, balancing his traditional, ominous Dracula themes with a lyrical melody for the love story between Paul and Alice. Linda Hayden and Isla Blair are lovely as the female victims, and Hayden does a fine job using her innocent face to ironic effect as she carries out Dracula’s evil orders (her wicked smile before she strikes the death blow is almost worth the price of admission). Ralph Bates does a nice arrogant turn as Courtley. Geoffrey Keen and John Carson are solid as two of the three “respectable” gentlemen, but Peter Sallis is the real standout as Samuel Paxton, obviously the junior member of the group, whom the other two browbeat mercilessly; his is perhaps he definitive screen embodiment of pathetic little man, and when he finally — if briefly and ultimately fatally — stands up for himself, the scene strikes with genuine dramatic force. Only Hammer stalwart Michael Ripper fails to impress: usually cast as a landlord, here he plays an unsympathetic police officer who makes Inspector Lestrade look like a genius by comparison.

Despite the erratic storytelling, the usual Hammer virtues are on display. The sets are atmospheric. James Bernard provides one of his best scores, balancing his traditional, ominous Dracula themes with a lyrical melody for the love story between Paul and Alice. Linda Hayden and Isla Blair are lovely as the female victims, and Hayden does a fine job using her innocent face to ironic effect as she carries out Dracula’s evil orders (her wicked smile before she strikes the death blow is almost worth the price of admission). Ralph Bates does a nice arrogant turn as Courtley. Geoffrey Keen and John Carson are solid as two of the three “respectable” gentlemen, but Peter Sallis is the real standout as Samuel Paxton, obviously the junior member of the group, whom the other two browbeat mercilessly; his is perhaps he definitive screen embodiment of pathetic little man, and when he finally — if briefly and ultimately fatally — stands up for himself, the scene strikes with genuine dramatic force. Only Hammer stalwart Michael Ripper fails to impress: usually cast as a landlord, here he plays an unsympathetic police officer who makes Inspector Lestrade look like a genius by comparison.

Despite the narrative lapses and the awkward interpolation of Dracula into the story, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA remains a powerful, albeit flawed, work that sustains interest on the basis of its thematic ambitions. Of all the Hammer Dracula sequels, this is the one with the most interesting idea at its core. If only it had done more justice to its title character, it might have emerged as a mini-masterpiece in its own right.

TRIVIA

Besides emphasizing the young characters, including a male lead apparently intended to suggest Paul McCartney, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA shows other signs of attempting to leaven its Gothic horror with a more contemporary sensibility designed to appeal to younger viewers. After Courtley’s death, there is a rather goofy high-angle shot that zooms in and out in time with a heartbeat sound effect; the scene has a vaguely psychedelic feel, like something out of a rock-n-roll movie. Later, when Paul is refurbishing the church, his ears are assaulted with inexplicable noises of unknown origin. The distorted sounds, heavy on the reverb, are more suggestive of a bad drug trip than the forces of evil.

A rumor on the Internet Movie Database suggests that Ralph Bates was originally scheduled to play Dracula in this movie, but this is incorrect. Bates was being groomed as a horror star to replace the aging Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing; in fact, Bates was cast in place of Cushing in HORROR OF FRANKENSTEIN, a sort of black comedy remake of CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN. However, Bates was always scheduled to play Lord Courtley in TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA: he was supposed to drink Dracula’s blood and return from the dead as a vampire, who presumably would go on to star in his own series of films. In effect, TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA, like BRIDES OF DRACULA before it, was designed as a Dracula film in name only; however, the character of Dracula was added later, at the behest of American distributor Warner Brothers, who insisted that the title character actually appear in the film. If Bates was ever intended for the actual role of Dracula, the subsequent sequel SCARS OF DRACULA would have been a far more likely candidate. That film abandons any continuity with its predecessors, suggesting that it was intended to jump-start the franchise, possibly with a new actor in the lead.

Another rumor is that TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA was planned as a teaming of Christopher Lee and Vincent Price. According to this story (perpetuated in a book about Price), the American horror star was to play a fourth member of the English thrill-seekers, but the budget was not large enough to accommodate both stars, so Price’s dialogue was divided up between the remaining three characters. No evidence exists to support this theory, which seem unlikely for the following reason: Hammer Films was reluctant to re-cast Lee as Dracula, because his salary was rising. Would they even have considered hiring Price, who was earning much more per film than Lee?

Peter Sallis, who plays the mousy little man Saxton, later became the voice of Wallace in the Wallace and Gromit stop-motion films.

DVD DETAILS

TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA was cut by Warner Brothers to receive a GP-rating for its U.S. release in 1970. The DVD restores the missing footage:

- The brothel sequence is considerably longer, including a suggestive dance performed by one of the girls with a snake. There are also brief flashes of nudity as Lord Courtley makes his way through the brothel, glancing behind curtains into cubicles where girls are entertaining clients.

- Courtley’s death was nearly incomprehensible in the GP version: one minute he was crawling on the floor, begging for help; then after a few kicks from his repulsed companions, there was a jarring cut to a high-angle shot looking down on the men, who were holding canes or swords above Courtley’s dead body. The DVD version shows the men react in disgust, begin kicking Courtley to keep him away, and then beat him with their canes, leading to his death.

- The death of each of the British thrill-seekers is capped with an additional sequence of three shots: a close-up of the dying man looking up in horror; a shot from their POV of Count Dracula looming triumphantly nearby; a final shot of the victim expiring. (One of these shots is in the trailer for the film, which is included on the DVD.)

TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA (1970). Directed by Peter Sasdy. Written by Anthony Hinds (as “John Elder”), inspired by the character created by Bram Stoker. Cast: Christopher Lee, Geoffrey Keen, Gwen Watford, Linda Hayden, Peter Sallis, Anthony Higgins, Isla Blair, John Carson, Martin Jarvis, Ralph Bates, Roy Kinnear, Michael Ripper, Anthony Corlan.

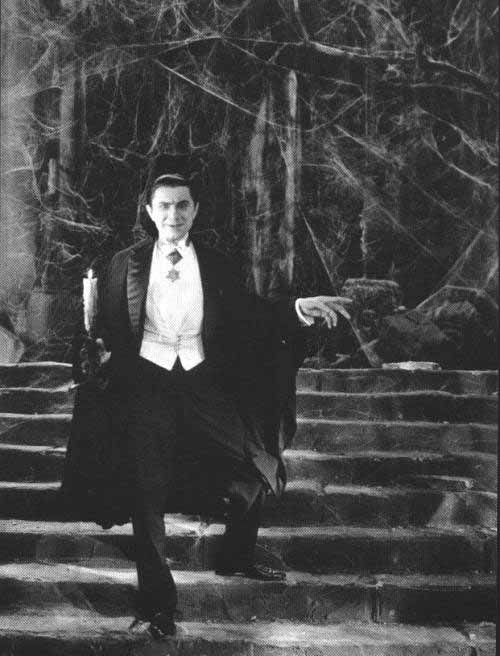

In an odd way, DRACULA benefits from its degraded reputation. Unlike many classics, which can have difficulty living up to expectations, DRACULA comes across reasonably well — in fact, better than expected — when reviewed today. It is taken for granted that the film is slow, talky, and memorable only for Bela Lugosi’s performance. So it is a pleasant surprise to find that much of the film actually does play well for an audience of eager fans. The first half is startlingly good, filled with delicious atmosphere and melodrama (beautifully captured in glorious black-and-white by Karl Freund’s mobile camera), and even when things slow down later, they never quite grind to a halt.

In an odd way, DRACULA benefits from its degraded reputation. Unlike many classics, which can have difficulty living up to expectations, DRACULA comes across reasonably well — in fact, better than expected — when reviewed today. It is taken for granted that the film is slow, talky, and memorable only for Bela Lugosi’s performance. So it is a pleasant surprise to find that much of the film actually does play well for an audience of eager fans. The first half is startlingly good, filled with delicious atmosphere and melodrama (beautifully captured in glorious black-and-white by Karl Freund’s mobile camera), and even when things slow down later, they never quite grind to a halt.