“Ah! The good old time – the good old time. Youth and the sea. Glamour and the sea. […T]ell me, wasn’t that the best time, that time when we were young at sea, young and had nothing, on the sea that gives nothing.”

– Joseph Conrad, “Youth: A Narrative.

Yes, the glories of a youth are a treasure trove of riches that shine on like dusky jewels buried in the pirate chest of one’s memory. For me, however, that “good old time” of Youth and Glamor had nothing to do with the sea. My dark ocean was the cinema screen; my luxury liner was the local theatre; my ticket was still a ticket, but my ports of call ranged from when dinosaurs ruled the Earth, to the Dawn of Man, to Beyond the Infinite. Unlike “the sea that gives nothing,” the vast timeless ocean that I explored – of past, present, and future – gave me everything: amazing adventure and enchanting excitement, fear and fantasy, and most of all – that grandeur of awe that first evokes a Sense of Wonder. I may have resided in a small, unexceptional suburb a half-hour east of Hollywood, but thanks to movies – particularly cinefantastique – my mind soared through the stars: I never felt earthbound, trapped, limited; infinite vistas always lay before me, for little more than a quarter.

Recollecting these hours upon hours spent gazing up at the flickering images on the silver screen, the verbal temptation is to joke about my “misspent” youth, but I cannot deem it so. So much of our identity – so much of our very selves – is derived from our memories. So much of who we are is expressed in our dreams. For me, memories and dreams merge in the movie houses of my youth, and in retrospect I cherish every moment – the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Perhaps strangely, I do not harbor a particular fascination for the films of the ’60s and ’70s, except in so far as I relate to them personally. I do not think the films of my youth represent the apex of cinema, nor do I wax nostalgic for the good old days. Many of my favorite movies come from earlier eras; just as many, perhaps more, arrived in the ’80s, ’90s, and on into the present day. Yet there is some kind of magic about the classics of yesteryear.

For me, “classics” always referred to films made before I was old enough to book passage: the Universal films of the ’30s, the Hammer horrors of the ’50s. However, as my luxury cinema liner continues to carry me to new and ever more modern and exotic ports – places of enchantment, mystery, and horror – I realize that many of my past journeys were to places that, although new at the time, have since become cherished by subsequent generations, who regard with reverential awe what I now take for granted.

This concept rammed me like an unexpected iceberg during a cybersurfing trip to Horror Movie a Day, where Brian Collins lamented in this post:

My biggest regret as a human being is that I wasn’t born in 1959 or so. I would have loved to have been a kid in the 70s, getting to experience pretty much all of my favorite horror films when they were first released, instead of 10-20 years later, after many of them had their impact blunted by ripoffs (and now remakes).

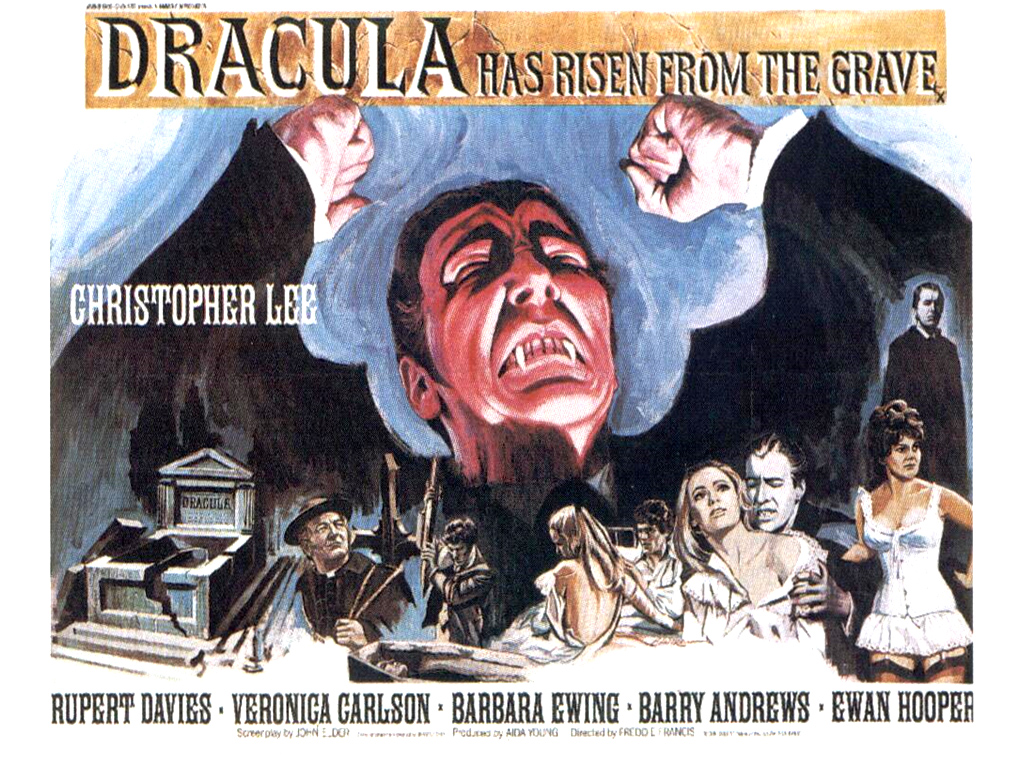

Perhaps it was just a cosmic coincidence, but I prefer to think of it as an omen that Brian named my year of birth. Hence, I am launching this semi-regular feature, a sort of travelogue of my past cinematic voyages, from the depths of darkness to the shores of space. Casting my mind back over the many far-off lands I visited from the comfort of my first-class passenger seat in the local movie house, I recall that my very first solo voyage (that is, sans parents) was to a double bill of Hammer horror, DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE and FRANKENSTEIN MUST BE DESTROYED (1968).

DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE is the third Hammer horror film to feature Christopher Lee as the Count, although I did not know that at the time. I had seen the last few minutes of REVENGE OF FRANKENSTEIN on television, so I had a glimpse of Hammer’s horror output even though I was ignorant of their history. Thanks to movies like FRANKENSTEIN’S DAUGHTER (1958), I knew that low-budget filmmakers would sometimes cash in on a famous character name, creating pseudo-sequels to the classic Universal monster movies of the 1930s (which I had seen on late-night television with my parents). I assumed that DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE and FRANKENSTEIN MUST BE DESTROYED were examples of this strategy; I had no idea they were genuine sequels to the earlier Hammer films, HORROR OF DRACULA (1958) and CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1957).

I cannot remember exactly when this double bill reached the El Monte Theatre, but it was at least a year or two after films were produced. The advertisement in the local papers listed the titles along with their ratings: G for DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE, GP for FRANKENSTEIN MUST BE DESTROYED. Since the GP rating replaced the old M-rating in January of 1970, it is safe I enjoyed this experience sometime before my eleventh birthday (which took place in December).

My siblings and I importuned our parents to take us to the film; they had taken us to other mature movies (including the M-rated BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID), but for some reason they decided not to attend these horror movies, leaving us off at the theatre for the very first time. The ratings system had only been around for a couple years, and there were then (as now) concerns about too much violence on screen. Uncertain about the new GP rating (which had replaced the M for Mature Audiences), my dad asked the girl behind the ticket window whether these movies were “okay for kids,” and she assured him they were.

Back then, tickets for kids cost fifty cents. We got some money to buy popcorn and sodas, too. Then we took our seats; the lights went down; the screen opened; and the film began. It is safe to say I have never been the same since…

I’m not sure what we were expecting. We had seen horror movies on television, but they were usually old black-and-white films that relied on atmosphere and suggestion. Even then, we knew that films on TV were often cut (we would hear our parents complaining about scenes missing from films they had seen in theatres), and we knew that the rating system had been invented to deal with the increasing amount of on-screen bloodshed. Ther very fact that we were sitting in a movie theatre, about to watch a horror film, meant we might be seeing something we had never seen before – maybe even (thanks to the confusion fo the ratings system) something that we were not meant to see…

DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE begins with big bold titles that give a sort of psychedelic impression of exploding corpuscles. I didn’t know anything about directors and screenwriters then, but I think I had read Bram Stoker’s novel and recognized his name on screen (the credit reads something along the lines of “based on the character created by…”). There followed a brief prologue, with a bell-ringer seeing blood dripping down the rope he is pulling. This leads him to investigate the church tower above – and the youthful audience in my local theatre screamed in fright as a woman’s body flopped upside down from its hiding place, stuffed inside the bell.

This was the first of many frights that day, but in general I did not find DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE to be particularly terrifying. I had always had a fondness for the Count and his vampire brethren, based on my fondness for bats. Although this version of Dracula (personified by Christopher Lee) did not turn into a flapping rubber vampire bat, the association in my mind was still strong, and the Count’s long black cloak was enough like bat-wings to suggest the similarity. I liked Dracula, and even though I knew he had to die, I didn’t particularly want to see him go. In a way, I was rooting for him, not frightened by him.

No, the enjoyment I got from this vampire film was more along the lines of excitement. Although I could not articulate it at the time, I must have sensed that this was a glossy well-made film, filled with atmosphere and action. I might have said it was “fun.” Today, the word I would use is “enthralling.” Certainly, my siblings and I – along with the rest of the young viewers – were as much under Dracula’s spell as any on-screen victim.

But to continue…

One year later, Msgr. Muller (Rupert Davies) finds the locals in Klausenberg still living in fear of the departed Dracula, so he and the local priest (Ewan Hooper) head up to the castle to read a rite of exorcism. The Count makes his first appearance after the local priest lags behind, falls and cuts his head, his blood seeping through the broken ice to revive the vampire. The sight of the bloody lips savoring the rejuvenating fluid elicited a loud communal “EWWWWWWW!” from my fellow theatre-goers.

Dracula turns the priest into a slave and sets out to avenge himself against the Msgr. Muller for putting the cross on his castle. Vampire and assistant head to Muller’s home town in a carraige; the slightly speeded-up footage of the Count furiously whpping the horses, his face twisted in demonic anger, drew gasps of excited approval from the crowd in the movie house. (We didn’t wonder where the horses had come from. Had they survived in Dracula’s stable for a year without anyone to look after them, or were they stolen – like the coffin the priest digs out of the ground so that Dracula will have a resting place in the far-off city?)

Muller’s niece Maria (Veronica Carlson) is in love with Paul (Barry Andrews), but Muller disapproves because Paul is an atheist. Dracula claims Zena (Barbara Ewing) as his first female victim but soon sets his sights on Maria. Muller tries to protect her, but the local priest wounds him fatally. Paul takes over, but being an atheist he refuses to pray after driving a stake through Dracula’s heart.

This scene, with its over the top gore, was a highlight of that long-ago afternoon. Kids gagged in horror as the stake went in; they gagged louder when the blood started to spurt; and they really started to scream when the camera cut in for a closer look. Best of all was the big surprise: we had thought this was the end of the movie, but the vampire managed to pull the stake out of his chest and survive! If Dracula is to be portrayed as a fearsome foe, then he should not be easily killed off, and Paul’s horrible moment of realization – that he was now face to face with a vampire who was holding the stake in his hand like a spear, ready to hoist the would-be vampire slayer on his own petard – was worth the price of admission.

Dracula absconds with Maria and heads back to his castle, ordering her to toss the offending cross over the battlements. Paul pursues, and a struggle ensues. Dracula ends up falling over the battlements and impaled on the giant cross, while the local priest, the vampire’s spell broken, says the necessary prayer to ensure that the vampire will die. It is the major, enduring miracle of DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE that, after the aborted staking scene, the film actually manages to top itself with the even more spectacular “crucifiction” finale. With the cross wedged in from behind, there was no way that Dracula was going to reach around and pull it out, and the screams of horror in the theatre echoed louder than ever before, amplified by the sight of the vampire weeping blood. The echoes started to fade only when the credits rolled, superimposed over a wide-shot of the empty cross, with Castle Dracula in the background, the Count’s body apparently having disintegrated off-screen.

I cannot recall the exact conversation after the lights went up, but it is safe to say we were stunned – and not in a bad way. There was a sense that we had perhaps transgressed in some sense – seeing more than our parents might have wished us to see, despite the imprimatur of the MPAA’s G-rating. Yet we knew we had seen something good. It might or might not give us nightmares (I never had any), but this was the kind of film that you told people about, relating the juicy details to your jealous friends who had not been so fortunate as you to see the movie.

I have to admit that I was not totally pleased with DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE. I had dressed up as Dracula for Halloween, and to my young eyes, the pasty vampire makeup on Christopher Lee looked no better than the chalk-white that had been applied to my own face. (Looking back, I realize that the idea was to make Lee’s Dracula appear older in this film, to create a visual contrast with the young ingenues.) I was also disappointed that we never saw the inside of Castle Dracula – the exterior promised so much, but just when the Count was about to take his new bride home and set up house, Paul came along and ruined everything!

Having been raised in the Catholic Church, I totally got the religious subtext of the film, the Battle between Good and Evil. I knew Dracula was alligned with the Devil, and it was up to the Church to send him back to Hell. Of course, the script plays around with this a bit, but Barry Andrews (as Paul) is so clearly a decent person – a scholar who makes a point of giving an honest answer instead of an easy lie – that you know he is on the side of the angels even if he does not believe in them. (It was not until years later, when I became a fan of the Who, that someone pointed out Andrews’ resemblance to vocalist Roger Daltrey.)

Also magnificent was Count Dracula’s reluctant Renfield – a priest who becomes the vampire’s slave because of his own human weakness. This seemed to suggest that, whatever the ideals of the Church, it took a man with some courage to live up to it, and that courage was not always found within those who professed to believe those ideals. Not profound by adult standards perhaps, but it added something extra to the movie.

I’m sure I was too young to fully appreciate Barbara Ewing and Veronica Carlson, but I was not blind to the suggestive costumes that the former wore in her barmaid role, and I could not help noticing that the film contrived to open Carlson’s blouse for one or two scenes. Both women were obviously pretty, but Carlson in particular was gorgeous; she really is forever embedded in my mind as the ideal of the vampire’s victim – buxom, blond, and beautiful.

The sexual undertones of DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE were also quite oblivious to me and (I imagine) the rest of the audience, who were all about my age. When Maria has to get a drunken Paul into bed, it only struck me as a little embarrassing for her when she had to bring herself to undress him. It never occurred to me that the cutaway, after Paul awakens and embraces her, indicated that they had had sex. Likewise, Dracula’s embrace of both women registered as bloodlust, not lust. It was food he was after, not sex, and I’m sure we all assumed that the heaving bosoms on display were simply an attempt to lure in older teenage viewers, in the same way the Raquel Welch’s presence in ONE MILLION YEARS, B.C. would sell tickets to people who didn’t like dinosaurs.

In retrospect, I realize that Dracula’s visit to Maria’s bedroom was probably the first sex scene I ever witnessed on screen. Sure, it was disguised as blood-drinking, but it was still about the exchange of bodily fluids between a man and a woman. Of course, this had always been latent in the vampire mythology, but DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE pushed the envelope quite a bit. It was not just that Veronica Carlson was gorgeous and profoundly sexually attractive; it was that she was the Good Girl, the innocent blond, yet she welcomed Dracula almost as enthusiastically as the barmaid. As a child, I assumed the Count put a hypnotic spell on his victims, the mise-en-scene suggests something else, a sort of willing seduction to which Maria succumbs without much if any struggle. The implications are bizarrre to say the least: Do women – even the pure and innocent – yearn for overpowering strangers to ravish them in their bedrooms? No doubt it is just as well that this element sailed right past me, because I doubt my ten-year-old mind could have processed it. It would take some heavy-duty psychoanalysis to determine whether that first viewing had a lasting effect on me, but I do know that the scene still stirs up some dark waters; beneath the rippling waves are distorted glimpses of domination-submission, sado-masochism, and even necrophilia. If only my parents had known, when they bought our tickets and left us off like passengers boarding a ship, to what strange destination this dark voyage would take their children!

Looking back, I am also amazed at the way DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE conveyed more than it showed. Although the impact is somewhat muted decades later, there is a nice moment when Dracula’s attitude shifts from seductive to lethal toward Zena. All we see is the change of Chirstopher Lee’s expression; his hands grip Barbara Ewing’s shoulder’s tightly; she screams, and a red filter descends over the image as the scene fades. We know the Count is going to drain her dry, without having to see it happen…

This is followed by perhaps the grizzliest sequence, in which the Count orders the priest to dispose of Zena before she can be reborn as a vampire. Again, we do not actually see what happens, just the image of the priest carrying her body toward the furnace. The dancing red firelight, reflecting off the actor’s sweating brow, conveys what is going to happen in a way that was perfectly revolting to my ten-year-old mind – probably the most genuinely frightening scene for me at the time.

I would go to many more horror movies at the local theatre, sometimes with my mom and/or dad, sometimes with my brother and sister, and later alone. This was a good time for horror films, at least in quantity if not quality, with new titles arriving on marquees on almost a weekly basis. Unfortunately, this was also a time when wretchedly awful movies (which today would be consigned to video oblivion) played on the big screen, and thanks to the relatively recent ratings system, censorship was deader than a crucified vampire, allowing exploitation filmmakers to push the limits of a GP (later PG) rating with blood-and-gore, revealing costumes, and even occasional flashes of nudity. I enjoyed many of these, but few had the same impact as DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE – which set the standard for all the followed.

The film provided the yardstick that has stayed with me the rest of my life. I have always known, despite howls of outrage from concerned moral guardians, that horror films can be violent and sexy without harming the minds of young viewers. Furthermore, based on this film, I always sensed in some intuitive way that even the most horrific subject matter could be entertaining and fun – a truly cathartic, satisfying experience. Other films with the same amount of gore – or even less – might merely disgust with their shoddy cinematic technique, but DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE proved that a little craftsmanship and – dare I say it? – artistry could transform disreputable material into a kind of art.

I did not know it then, but this was the beginning of a life-long love for Hammer horror. Eventually, I would discover the earlier, even better films (made before the company began recycling all their hits), but DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE continues to hold a special place in my heart. Thanks to broadcast television, cable, revival screenings, and DVD, I have seen DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE many, many times over the years, but I would not trade that first experience for anything.

Of course, I experienced a one-two punch on that day, Count Dracula sharing the screen with his fellow titan of terror, the Baron, who appeared in FRANKENSTEIN MUST BE DESTROYED. Unlike DRACULAS HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE, the Frankenstein film did terrify me, but I will leave that experience to form the next chapter in this travelogue…

ADULT PERSPECTIVE

So, that is what DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE meant to me as a child, and later as a teenager when I saw the film again on television (usually with the close-up of the stake through the chest deleted). How do I view the film now, as an adult? Is it pure nostalgia value, or does this trip to Transylvania still have sights worth seeing through more mature eyes?

Having now seen all the Hammer Dracula’s many times over, I can fairly say that DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE is a slight step down from the HORROR OF DRACULA and the almost (but not quite) as good DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS. Some of the freshness has gone out of the franchise, and screenwriter Anthony Hinds (using his “John Elder” pseudonym) seems not to know what to do with the Count, so instead he concocts a love story about two other characters and uses Dracula as a plot complication. Fortunately, the production values and Gothic atmosphere remain as lush as ever, and former cinematographer Freddie Francis does a spectacular job in the director’s chair, milking every scene for maximum visual impact, emphasizing not only the Gothic horror but also the romance. He puts the camera in close during Dracula ravishment of Maria, creating a seductive intimacy that goes even a little bit beyond what director Terence Fisher had focused on in HORROR OF DRACULA and DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS.

As often happened in the Hammer Dracula series, the Count seems motivated by petty revenge, which he executes mostly through his assistants (in this case the priest and Zena). The real focus of the story is on Paul and Maria, whose love is thwarted by Paul’s atheistic beliefs (and on his insistence on expressing them to Maria’s Catholic uncle!). The only connecting link between this pair and Dracula is Maria’s uncle. As a result, the story seems a bit arbitrary and stitched together, without the strong, usually action-packed narrative line displayed in the best of Hammer’s classic horrors.

Nevertheless, DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE contains several interesting ironies, with the weak-willed local priest falling under the vampire’s spell, while the non-believer Paul is Dracula’s chief adversary. Not unexpectedly, Paul becomes a believer by the end, after seeing the power of the cross destroy the Count. Clearly, writer Anthony Hinds was trying to exploit the religious subtext of the Dracula myth. Even the title rings a note reminiscent of the resurrection of Jesus in the New Testament, and surely it is no accident that Dracula is almost literally crucified at the end — in one of the most spectacular demises ever suffered by the vampire, who weeps tears of blood as he expires.

Unfortunately, the portrayal of Count Dracula as an Antichrist figure is mostly symbolic. Absent from the script is any action that shows him devoted to the grandeur of evil; he behaves like a run-of-the-mill, garden variety vampire, leaving it up to Christopher Lee to imply the character’s stature as the “Prince of Darkness” in his performance. This he accomplishes to a great degree with little more than body language and screen presence, although he is aided by a few masterfully lit and composed shots that emphasize the brooding stillness of the Count as he lurks in shadows, awaiting his next victim. In a matter of a few seconds, these images convey a tiny glimpse of what immortality must be like for the vampire.

Also heavily emphasized in DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE are the sexual undertones inherent in vampire mythology. Count Dracula’s first female victim is a dark-haired woman of easy virtue who had tried to seduce Paul. Yet the blond and apparently innocent Maria turns out to be not that different from Zena: not only does she sleep with Paul (even though they are not married); she also overtly responds to Dracula’s advances when he sneaks into her bedroom. Francis puts his camera in close, heightening the tension and the eroticism, which is much more seductive than that seen in HORROR OF DRACULA (which more resembled a rape). Here, the vampire lover gently nuzzles Maria’s neck first, as if sensitizing her skin for the bite to come. And Christopher Lee eschews his trademark red contact lenses for the close-ups of his eyes, implying that it is not blood lust that is so much motivating the Count.

As in many good horror films, the simplicity of the story does stir up some interesting imagery that resonates on a deeper, mythic (sometimes even subconscious) level. The trek by Dracula and Maria back to the castle features the woman clinging to his coffin as if yearning for a lover. Later, she follows through the woods, the camera tilting down to her bare feet, emphasizing her indifference to her own pain as she follows her new vampire lord and master. Then, in a quick ironic shift, we dissolve to the Count carrying her up the rocky terrain toward his castle, looking for all the world like a bridegroom carrying his beloved to the threshold.

Although G-rated, DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE hardly seems tame. There is no actual nudity, but both Barbar Ewing and Veronica Carlson display their ample charms, either in corsets of low-cut dresses. And the gore is plenty effective, too, particularly during the failed staking of the vampire. Although some purists (including Lee himself) have objected to this scene, it works wonderfully and gives some hint as to how the Vampire King could have survived for centuries – destroying him with a wooden stake just is not as easy as it looks. The final “crucifiction” scene does not feature as much flowing blood, but it is just as grizzly, with the pont of the cross producting from Dracula’s chest. Francis serves up a variety of camera angles, giving ample screen time for Lee to register the Count’s helpless agony on an almost operatic level of melodrama.

The cast is strong. Christopher Lee, as always, makes Count Dracula a formidable figure, both frightening and alluring; even if the script does not serve him well, he makes the most of his scenes, indelibly impressing himself on the audience imagination with all the force of an archetype that needs no distinguishing details.

Rupert Davies does a good job as his chief religious opposition, and Ewan Cooper creates a wonderfully weak portrait of the priest who falls under the vampire’s spell. Stalwart character actor Michael Ripper lends amiable support, and Barbara Ewing makes a good first victim, perfectly registering sexual attraction to the Count and then jealousy when he turns his attention elsewhere. Barry Andrews has the right charm and charisma to pull of the young male lead role, and Carlson is absolutely gorgeous – the perfect embodiment of “Dracula’s most beautiful victim” (as she was called in some of the film’s promotional materials).

James Bernard provides another rousing score, reusing his famous three-note Dracula motif (the orchestra almost seems to be singing “DRA-cu-la!”). And Bernard Robinson’s sets are wonderful as always (although it is disappointing that we never see the interior of Castle Dracula). If only the script had been able to meld is religious and sexual motifs into a stronger narrative that did full justice to the Dracula character, then DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE could have taken its place alongside HORROR OF DRACULA as genre masterpiece. As it stands, this is an above-average sequel that lingers in the mind thanks to its memorable imagery and directorial flair.

TRIVIA

DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS (1965), the previous film in the series, had ended with the Count sinking beneath the icy waters around his castle. DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE was trying to pick up directly from where its predecessor left off by showing the vampire revived from beneath the ice. However, the script fudges continuity a bit: We are told that Dracula killed the woman found in the bell-tower in the prologue – an even that took place one year before the main action of the film. Since Dracula had been dead during the ten years of screen time that separate HORROR OF DRACULA (1958) from DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS, the bell-tower even must have taken place sometime during the later film; however, the Count certainly did not seem to have time for this diversion during the frantic back-and-forth action of PRINCE OF DARKNESS.

This is the first Hammer Dracula that presents “Count Dracula” as a household name familiar to all the characters: When Msgr. Muller announces that the vampire is alive, his sister-in-law gasps in horror, obviously knowing who – and what – he is talking about, without any further explanation. This has the unfortunate side-effect of reducing the tone to the level of an old-fashioned, melodramatic horror movie, abandoning the more modern approach of Hammer’s previous Dracula films, which had avoided such histrionics.

This is the first time that Christopher Lee speaks as Dracula since the opening scenes of HORROR OF DRACULA. The character remained mute throughout the later portions of that film and throughout the entirety of the sequel, DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS. Curiously, Lee abandons the fast-paced, authoritative voice he used in HORROR OF DRACULA, here opting for a slower-paced, sepulchral tone.

This is the first of Lee’s Hammer Dracula films in which we do not see the interior of Dracula’s castle. This will happen again in the next film TASTE THE BLOOD OF DRACULA, as well as the later DRACULA A.D. 1972 and THE SATANIC RITES OF DRACULA. Only SCARS OF DRACULA will show us Lee at home in his castle once again.

Terence Fisher, who had helmed Hammer’s three previous “Dracula” films (including BRIDES OF DRACULA, in which the Count does not appear), was scheduled to direct DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE, but he injured in a car accident while crossing the street and had to drop out of the project. Although his replacement, Freddie Francis, brought a refreshing visual style to the film, loaded with nifty camera angles and atmospheric staging, it seems likely the Fisher would have hammered out the screenplay’s narrative kinks if he had had the chance.

DVD DETAILS

DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE is available in a bare-bones DVD presentation from Warner Brothers. The disc offers English and French audio tracks with optional English, French, and Spanish subtitles. The only bonus features is a theatrical trailer. The transfer mattes the full-frame image to the 1.85 aspect ratio of theatrical screenings, and the picture has been enhanced for widescreen televisions. The transfer displays all the artful color of the photography (including Freddie Francis trademark use of a custom-made filter that shades off lighting toward the edge of the frame, creating a “spotlight” effect toward the center). In fact, the use of color recalls some of the best work scene in the Gothic films that Italian Mario Bava (another cinematographer-turned-director) was making during the same decade.

There is a nice piece of cover art on the front. The back features a close-up of Lee in his Dracula makeup. The inside cover lists the 23 chapter stops, which are printed over a gruesome color shot of Lee with blood streaming out his chest from the stake in his heart. Artwork on the disc features an image of Lee’s face lowering toward Carlson, who rests her head on a pillow – a composition later echoed during the infamous “head” scene in REANIMATOR (1985).

DRACULA HAS RISEN FROM THE GRAVE (1968). Directed by Freddie Francis. Screenplay by John Elder (Anthony Hinds), based on the character created by Bram Stoker. Cast: Christopher Lee, Rupert Davies, Veronica Carlson, Barbara Ewing, Barry Andrews, Ewan Hooper, Michael Ripper.

Picking up from the disappointing ATTACK OF THE CLONES, this film finally showed audiences the only plot development that made the prequel trilogy (including THE PHANTOM MENACE) interesting: how Anakin Skywalker turned to the Dark Side of the Force and became Darth Vader. Despite some quibbling, the critical consensus emerged that this is the best of the three prequels, even if it fails to live up to the glory of the original STAR WARS trilogy (particularly the original and its first sequel THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK).

Picking up from the disappointing ATTACK OF THE CLONES, this film finally showed audiences the only plot development that made the prequel trilogy (including THE PHANTOM MENACE) interesting: how Anakin Skywalker turned to the Dark Side of the Force and became Darth Vader. Despite some quibbling, the critical consensus emerged that this is the best of the three prequels, even if it fails to live up to the glory of the original STAR WARS trilogy (particularly the original and its first sequel THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK).

Tonight, as part of their 7th Annual Festival of Fantasy, Horror and Science-Fiction, the American Cinematheque will screen HORROR HOTEL at the Egyptian theatre in Hollywood. This film was known under the somewhat more atmospheric title of CITY OF THE DEAD in its native England (it really should have been called THE THIRTEENTH HOUR, but no one asked me); unfortunately, the Cinematheque seems to be screening the U.S. version, which not only changed the title but also deleted two minutes of footage. Still, any excuse to discuss this excelelnt exercise in atmosphere is good enough for me. It freaked me out when I first saw it as a kid on TV, and subsequent opportunities to enjoy it n the big screen (thanks to previous Cinematheque screenings) have proven that it holds up to adult scrutiny. It may not be a complete masterpiece, but as a cult item it certainly is a gem worth discovering for yourself.

Tonight, as part of their 7th Annual Festival of Fantasy, Horror and Science-Fiction, the American Cinematheque will screen HORROR HOTEL at the Egyptian theatre in Hollywood. This film was known under the somewhat more atmospheric title of CITY OF THE DEAD in its native England (it really should have been called THE THIRTEENTH HOUR, but no one asked me); unfortunately, the Cinematheque seems to be screening the U.S. version, which not only changed the title but also deleted two minutes of footage. Still, any excuse to discuss this excelelnt exercise in atmosphere is good enough for me. It freaked me out when I first saw it as a kid on TV, and subsequent opportunities to enjoy it n the big screen (thanks to previous Cinematheque screenings) have proven that it holds up to adult scrutiny. It may not be a complete masterpiece, but as a cult item it certainly is a gem worth discovering for yourself.