This 1896 black-and-white silent horror film from George Melies (the special effects pioneer behind 1902’s A TRIP TO THE MOON) probably yields little gooseflesh for today’s viewers. However, it plays like an overture for the next forty years of horror movie imagery; its brief running time encapsulates such soon-to-be-familiar cinema imagery as old dark castles; flapping bats that transform into human figures; and a brandished cross to ward off the evil being haunting the castle. As always with Melies, believability is less important than amazement – and amusement. Although less overtly comic than some of his films, the occasional whimsical gag works its way in. Unfortunately, the ending seems a bit truncated, but you still get the general idea.

[serialposts]

Tag: black-and-white

The Man with the Rubber Head: Video

This is one of many amusing silent short subjects from George Melies, the early cinema magician who pioneered the use of special effects to create imaginative and whimsical fantasy on screen. Typical of Melies, there is little story; THE MAN WITH THE RUBBER HEAD is more of an extended sight gag, in which the special effects serve to render the impossible in a manner that is far from believable – and a good thing too; otherwise, the climactic exploding head would be grotesquely horrific!

[serialposts]

Le Diable Noir (a.k.a., The Black Imp, 1905): Video

This 1905 effort from George Melies may not be as famous as A TRIP TO THE MOON (1902), but LA DIABLE NOIR (or THE BLACK IMP) is a perfect distillation of the the silent movie magicians craft and art. The movie tells the simple story of a customer in a hotel room bedeviled by the titular character. (I actually prefer the term “imp” because of the impish pranks that ensue). An amazing series of gags are squeezed into the short running time – I refuse to call them “effects” because the actions really are a series of slapstick sight-gags that build in the manner of a great silent comedy. Filmed from a single camera angle, THE BLACK IMP at first seems dated in its technique, but ultimately the unblinking and unmoving camera becomes a plus rather than a negative, watching as the action unfolds in real time, without a (visible) cut to telegraph to the viewer (however subliminally) that some kind of set-up has been prepared to realize the next magical illusion.

In short, this is four minutes of whimsical fun that should bemuse anyone with a Sense of Wonder.

[serialposts]

The Innocents: Cinefantastique Spotlight Podcast #4

The fourth installment of the Cinefantastique Spotlight Podcast focuses its attention on the 1961 classic THE INNOCENTS. This ambiguous and haunting ghost story was produced and directed by Jack Clayton, based on Henry James’ novel The Turn of the Screw and William Archibald’s stage adaptation, The Innocents. Oscar-winner Freddie Francis supplied the atmospheric black-and-white photography, and Oscar-nominee Deborah Kerr starred as governess Miss Giddens, put in charge of two apparently innocent children who may – or may not – be in league with ghosts. Lawrence French, Arbogast (of Arbogast on Film), and Steve Biodrowski struggle to penetrate the miasma of secrets surrounding this intriguing film, one of the great achievements in the horror genre.

Consider this the first installment in this year’s 50th Anniversary Celebration of the Horror, Fantasy & Science Fiction Films of 1961. As we did in 2010, Cinefantastique will offer periodic posts and/or podcasts throughout the year, looking back at the great genre achievements of five decades ago.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

[serialposts]

Upstaged By The Invisible Man: Gloria Stuart Interview

Recollections from the late actress on working with director James Whale on THE OLD DARK HOUSE and THE INVISIBLE MAN

Today’s mainstream audiences remember the late Gloria Stuart, who died on September 26, 2010, for the box office blockbuster TITANIC, but for cult fanatic and horror buffs the actress holds a special place in film history, having worked with FRANKENSTEIN-director James Whale on two of his classic horror pictures, THE OLD DARK HOUSE (1932) and THE INVISIBLE MAN (1933). In these films – more than in FRANKENSTEIN and, perhaps, even its sequel BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN – Whale indulged his penchant for sly humour, using the conventions of the horror genre as a springboard for satire and black comedy.

In both cases, Stuart had the possibly thankless task of’ playing the leading lady – that is, one of the normal characters whose lot on screen is to act as the equivalent of a straight man in a comedy team, while the eccentrics or the mad scientist gets all the good lines. Nevertheless, she managed to inject a little personality into her roles, and even garnered some of the laughs in THE OLD DARK HOUSE when her character, Margaret Waverton, alone and unprotected in the titular manse, notices the spooky shadows cast by the firelight – and instead of reacting in fear, proceeds to make a series of hand-shadows on the wall.

In both cases, Stuart had the possibly thankless task of’ playing the leading lady – that is, one of the normal characters whose lot on screen is to act as the equivalent of a straight man in a comedy team, while the eccentrics or the mad scientist gets all the good lines. Nevertheless, she managed to inject a little personality into her roles, and even garnered some of the laughs in THE OLD DARK HOUSE when her character, Margaret Waverton, alone and unprotected in the titular manse, notices the spooky shadows cast by the firelight – and instead of reacting in fear, proceeds to make a series of hand-shadows on the wall.

Gloria Stuart started her film career in the early 1930s as a contract player at Universal Pictures, the studio where Whale had made FRANKENSTEIN. Her third picture was THE OLD DARK HOUSE, which is one of the earliest examples from the sound era of the now-familiar archetypal horror film plot: a group of innocent travelers is forced to take shelter in a scary house filled with strange characters, in this case the Femms, a family ranging from the eccentric (Ernest Thesiger and Eva Moore as brother and sister Horace and Rebecca) to the threatening (Boris Karloff as their butler) to the outright homicidal (Brember Wills as Said).

Rather like her character in TITANIC, Stuart had vivid memory of events from decades past. Of her stint on THE OLD DARK HOUSE, she recalled:

“It was wonderful working with James. He was brilliant. He came on the set every morning with the script, and on the blank side he had all the setups that he’d pencilled in the night before. It was very precise. He knew exactly what he wanted, which in those days for film directors was not usual, because most of them had been silent directors. They weren’t used to dialogue, and they weren’t used to directing dialogue; they were used to directing silent action. So it was refreshing working with him, particularly because I wanted to be a stage actress, and I was very snobbish about film. I felt I was slumming, but I need the money, and the money was in film.”

Although Stuart respected Whale as a director, she did not always understand the method to his madness. For example, when she and her compatriots first take shelter in the Femm household, Margaret Waverton changes from her wet clothes into a fancy evening dress, not at all suited to her gloomy surroundings.

“The gown was bias-cut, very pale pink silk-velvet,” she explained. “I said to James, ‘We come in out of the rain; we’re muddy; we’re tired. It’s late. And I change into this pale pink dress with jewellery. Why?’ He said, ‘Because, Gloria, when Boris chases you through the house, I want you to appear like a white flame.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’m a white flame, but I still don’t understand it.’ That’s how precise he was. When I change and get down to my chemise,” she adds with a laugh, “I had a big audience on the set.”

“The gown was bias-cut, very pale pink silk-velvet,” she explained. “I said to James, ‘We come in out of the rain; we’re muddy; we’re tired. It’s late. And I change into this pale pink dress with jewellery. Why?’ He said, ‘Because, Gloria, when Boris chases you through the house, I want you to appear like a white flame.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’m a white flame, but I still don’t understand it.’ That’s how precise he was. When I change and get down to my chemise,” she adds with a laugh, “I had a big audience on the set.”

Stuart credited Whale for adding humour to the film, a sort of tongue-in-cheek comic relief that plays off the awkward social tension in the scenario – for instance, Horace Femm’s forced civility at the dinner table, when he practically demands that each guest eat a potato.

“Ernest Thesiger was one of the great character actors,” said Stuart. “When he says, ‘Have a po-ta-to,’ and when he throws the bouquet of flowers into the fireplace, that’s all James. All those very sardonic, witty points of view and presentations – all James, not in the script. He was a wonderful man to work for.”

Stuart also credited the film with inspiring the creation of the Screen Actors Guild of America. She and Melvyn Douglas were the only US citizens in the cast; Karloff, Thesiger, Moore, Charles Laughton, Raymond Massey and Lillian Bond were English, and during production the Americans got a glimpse at how actors were treated outside Hollywood.

“THE OLD DARK HOUSE is the reason that you have SAG, with almost a million members,” Stuart claimed. “It was a wonderful happenstance. James imported all the English actors, with the exception of Melvyn Douglas, who had just come from the New York Theatre, and me.”

Stuart and Douglas noted that the English cast broke for tea at eleven and four each day – an option not offered to the two Americans.

“James joined all the English actors,” Stuart recalled. “So on one side of the set they had their ‘elevensies’ and `foursies,’ and Melvyn and I would be sitting together, not invited. One day, Melvyn said to me, `Are you interested in forming a union together?’ I said, ‘What’s a union?’ He said, ‘Like in New York – Actor’s Equity. The actors get together and work for better working conditions.’ I said, ‘Oh wonderful,’ because I was getting up at five every morning; in makeup at seven, in hair at eight, wardrobe at quarter of nine, and then sometimes if production wanted you to, you worked until four or five the next morning. There was no overtime. They fed us when they felt like it, when it was convenient for production. It was really very, very hard work. He said, `We’ll have a meeting, and we’ll try to get overtime, eight hour days, eight hours in between for ourselves.’ So I started working as an organizer for SAG. Actually, my union number is 183, because I was so busy canvassing and getting others to join, that I forgot to join myself. Anyway, I’m one of the few remaining founders of the Guild. That’s one reason I’m very grateful to THE OLD DARK HOUSE. I thank that English cast for having their elevensies and foursies.”

Afterward, Stuart appeared in several non-horror films at Universal, including one directed by Whale called KISS BEFORE THE MIRROR, which, according to Stuart “was considered very sexy in those days, but believe me, it wasn’t!”

Then in 1933 she played the fiancee of Jack Griffin, the ambitious scientist whose experiments turned him into THE INVISIBLE MAN. The titular role was essayed by Claude Rains; it marked his first “appearance” in film, although his face was not seen unti the final fadeout. THE INVISIBLE MAN also featured Una O’Connor in a supporting role; her over-the-top hysterical reactions to the strange happenings play like a preview of her similar role in Whale’s THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.

Stuart characterized the shooting as “an extraordinary experience,” adding that “we werent’ allowed on the set when Claude became invisible, and it was a very big thing on the Universal lot. There’s a reat deal of wit in ths picture, especially O’Connor.”

Despite the invisibility of his character, Rains did work with Stuart, during scenes in which Griffin is clothed, with his head wrapped in surgical bandage and his eyes covered with dark glasses.

“Claude had not made any films up until this time; he came from the New York stage,” said Stuart. “He was what we call ‘an actor’s actor.’ He was completely involved in being an actor, which doesn’t make for fun and games on the set. Besides,” she laughed, “he was shorter than I was, so either he was on a platform, or I was in a trough.”

Stuart found that Rains employed a few tricks he had learned on stage ot keep audience attention focused on himself, but thanks to the medium of film she managed to hold her own.

“On the stage, whatever happens goes that night, and you don’t go back and do it over again,” she explained. “The first day of shooting on the film, Claude and I had a scene together, and he would upstage me. He would take me [by the arm] and all of a sudden he’s with his full face to the camera, and I had my back to the camera. I stopped in the middle of filming – you don’t do that with Whale; he was a very strict disciplinarian – and I said, ‘James, look what he’s doing to me’ He said, ‘This is movies, not the theatre, and if we don’t get it right the first time, we can do it over again and again.’ Rains said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. Oh, Miss Stuart, please forgive me.’ I said, ‘It’s all right, Mr. Rains.’ The next take he was upstaging me again. I didn’t have to stop; James stopped it.

The final take features Stuart and Rains evenly blanace din the shot. “So our relationship during the – I guess it was normal between an actor’s actor and – well, I hope I’m not an actor’s actress,” laughed Stuart.

THE INVISIBLE MAN turned out to be Stuart’s last picture with Whale. Shortly thereafter, Universal sold her contract to Columbia Pictures, and she went onto appear in such films as Busby Berkeley’s GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935 (sort of the MOULIN ROUGE of its day) before retiring in the mid-1940s. During the decades that followed, she tried her hand at painting, and even learned to work a printing press in order to publish her artwork in coffee table books. Then – the mid-1970s, she started acting again, mostly in made-for-television movies like THE LEGEND OF LIZZIE BORDEN and TWO WORLDS OF JENNIE LOGAN, although she did appear in some theatrical films (including MY FAVORITE YEAR). Finally. in 1997, she gave an Oscar-nominated performance in TITANIC.

“For thirty-three years I’d been in the past, you might say, and Cameron brought me back,” Stuart recounted. “It changed my life completely. I was so reclusive, working hard with painting and printing. What happens to an Academy nominee is unbelievable. One day in my patio and on my front yard, there must have been four companies with cameras and lights setting up to interview me about ‘How does it feel to be an Academy nominee.’ After that. I’ve done so much in the last six years that I feel like I’m back in the business; I’ve become more active in the Screen Actors Guild, too. In my old age, I feel that anything I can do to help. I would like to.”

Looking back on her films, Gloria Stuart considered her two favorites to be THE OLD DARK HOUSE and TITANIC (“naturally”), but she seemed prouder of her work in the 1997 Oscar-winner. As for the older film, she gave all credit to the director.

“James Whale is a cult figure in England, and I think he should be here in the United States, too,” she said. “All of his films have great individuality; all of his films are imaginative and witty. He was an actor and a cartoonist, and a newspaper man. He brought all of his talent and his taste to film. I think that of all the directors I’ve worked for – with the exception of James Cameroa, who is a writer, a director, a producer, everything – James was the most wonderful man that I’ve worked with. He knew exactly what he wanted, having been an actor – which none of the other directors that I worked with had been. It’s very difficult, as an actor; if the director can’t tell you what he wants.”

This is a revised version of an article that originally appeared in 2003. Copyright by Steve Biodrowski.

Actress Gloria Stuart dies

Gloria Stuart, who earned an Oscar nomination at the age of 87 for TITANIC, died Sunday night, September 26. The 100-year-old actress had been diagnosed with lung cancer five years ago, according to the Los Angeles Times. Although Stuart is most well known to modern audiences for appearing as the older version of Rose (played in flashback by Kate Winslet) in James Cameron’s blockbuster about the ill-fated ocean liner, fans of cinefantastique remember her for starring roles in two classic black-and-white horror movies from the Golden Age of Universal Studios in the 1930s: THE OLD DARK HOUSE (1932) and THE INVISIBLE MAN (1933), both directed by the great James Whale.

Blond and beautiful, Stuart played the leading lady/romantic interest in both movies – typical roles for the period. However, being James Whale productions, both films have their share of tongue in cheek humor, in which Stuart was occasionally allowed to take part. In what looks like an improv, when her character Margaret Waverton is left alone in the titular spooky abode of THE OLD DARK HOUSE, instead of cowering in fear, she starts flashing hand-shadows on the wall, illuminated by the flickering fireplace

In a personal appearance at the Egyptian Theatre early in the 2000s, Stuart recalled that all of the campy humor in both films derived not from the scripts but from Whale (who liked to poke fun at the horror genre in which Universal had typecast him). Stuart also recalled that Claude Rains, with whom she starred in THE INVISIBLE MAN, was a bit of a scene-stealer. When performing dialogue together, Rains would grasper Stuart by the shoulders and subtly maneuver her so that her back was to the camera, leaving himself as the dominant figure in the shot.

In a personal appearance at the Egyptian Theatre early in the 2000s, Stuart recalled that all of the campy humor in both films derived not from the scripts but from Whale (who liked to poke fun at the horror genre in which Universal had typecast him). Stuart also recalled that Claude Rains, with whom she starred in THE INVISIBLE MAN, was a bit of a scene-stealer. When performing dialogue together, Rains would grasper Stuart by the shoulders and subtly maneuver her so that her back was to the camera, leaving himself as the dominant figure in the shot.

After her early stint at Universal, Stuart continued working into the 1940s, appearing in such films as BELOVED (1934) and GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935 (1935). After that, there is a 30-year gap in her filmography. She returned to acting in the mid-1970s, appearing in small roles in films and television. After another gap, this time of eight years, she returned to the big screen in TITANIC,which catapulted her back into the spotlight. She worked steadily until 2004, with more movie and television credits, including a guest stint, ironically, on THE INVISIBLE MAN series.

After her appearance at the Egyptian, Stuart was overheard answering a question about one of her co-stars in GOLD DIGGERS OF 1935. Her response was, “He’s dead, honey; they’re all dead.” Now at last Gloria Stuart has gone to join her co-stars in the great cinema in the sky. But as The Kinks’ Ray Davies said, “Celluloid Heroes never really die…”

The Wolf Man (1941)

A classic despite its flaws

A classic despite its flaws

This 1941 film is widely considered to be one of the classics of the horror genre, because it introduced the world to one of the most famous movie monsters of all time: Lawrence Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr.), an innocent man bitten by a wolf, who then succumbs to the curse of lycanthropy. After Count Dracula and Baron Frankenstein, THE WOLF MAN probably ranks third in the pantheon of Universal Pictures’ famous movie monsters. Unfortunately, the film itself is a classic without being an actual masterpiece. It is glossy and atmospheric, but it lacks the imaginative impact and artistic sensibilities of DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN (both made ten years earlier), relying on solid studio production values (sets and photography), plus its fine cast, to compensate for director George Waggner’s competent but not necessarily inspired handling of the material.

THE PLOT

The story follows Talbot (Chaney) as he returns to his ancestral home after a stay in America. He escorts two ladies to a gypsy camp where they have the fortunes read, but the fortune teller, Bela (played by DRACULA’s Bela Lugosi) is disturbed when he sees a pentagram in the hand of one of the girls – a sign that she will be the werewolf’s next victim. On the way home, the trio are attacked by a wolf, which Talbot kills with his silver-headed cane; however, Talbot (who was bitten in the struggle) is found next to the body of Bela.

An old gypsy woman (Maria Ouspenskaya) informs Talbot that Bela was a werewolf and his bite has passed the curse on to Talbot. Now he will transform into a wolf and kill against his will; the only way to end his cursed existence is with silver. The gypsy woman’s prediction comes true, when Talbot changes and kills a gravedigger. He tries to convince his friends and father, Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains), but of course no one believes him. Finally, late at night, he attacks Gwen (Evenlyn Ankers), but Sir John manages to kill him with his silver-headed cane, ending the curse.

ANALYSIS

Though fans of old movies sometimes think of horror films from the 1930s and 1940s as being equally classic, the later decade was actually an era marked mostly by rehashing old material. THE WOLF MAN is no exception, being basically a re-thinking of 1935’s somewhat overlooked THE WERE-WOLF OF LONDON. THE WOLF MAN, however, seems relatively fresh, because it is not a sequel but a new take on the subject matter. The studio’s earlier attempt at lycanthropy introduced the notion that a werewolf is not a man who transforms into a wolf but a monstrous hybrid who undergoes an involuntary transformation during the full moon and passes his affliction to others, with a bite. THE WOLF MAN incorporated and expanded upon this mythology, dropping the full moon and adding the idea that a werewolf is immortal and invulnerable – except to silver. Additionally, the werewolf became a less human, more beastly creature.

Chaney is not a sinister presence in the manner of horror stars Lugosi or Boris Karloff, but he is perfect casting for as Talbot – an initially easy-going fellow who gradually transforms into a guilt-ridden, tortured man as he becomes convinced that he is a monster. Also impressive is the makeup by Jack Pierce and the transformation special effects by John P. Fulton (a series of lap dissolves that show fur gradually appearing or disappearing). Apparently, a similar make up by Pierce had been intended for WERE-WOLF OF LONDON, but actor Henry Hull had refused to have his face completely covered with fur. Lon Chaney Jr was a better sport about the whole thing, with the result that he achieved cinematic immortality in the role that caught on in the public imagination, turning him into a horror star (the “New Lon Chaney,” as Universal called him, after his famous father, who had starred in Universal’s 1925 version of PHANTOM OF THE OPERA).

Nevertheless, THE WOLF MAN is riddled with flaws, the most obvious being that the filmmakers are inconsistent about whether or not a lycanthrope turns completely into a wolf or into a man-wolf hybrid. We are left to ponder why Bela Lugosi (the old generation passing on the curse of typecasting to the next generation?) is replaced by a real wolf when the full moon rises, instead of putting the actor in a werewolf makeup like Chaney’s. Also, Siodmak’s poetic speeches (“Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night/May become a Wolf when the Wolfbane blooms, and the Autumn Moon is bright”) wear out through repetition.

The film is also somewhat blunt and unsophisticated in its technique, showing its monster perhaps a bit too clearly, instead of using shadows and suggestion to work on the viewer’s imagination. This is a complete reversal of what was intended in Siodmak’s original script, which left the question open of whether Talbot really transformed into a wolf or only thought he did. Much of the material relating to this psychological interpretation remains in the script: there are constant references to psychology and the mind; even the term “lycanthropy” is defined not as turning into a werewolf but as a delusion of turning into a wolf. Consequently, the finished film seems ever so slightly schizophrenic, laying the groundwork for an ambiguous approach that is abandoned in favor of a full-blown monster movie.

The decision to show the Wolf Man clearly appears to have beena last minute one. There is little footage of the monster (which inevitably disappoints younger viewers), some of which is repeated. The monster scenes betray some continuity lapses (Talbot takes off his shirt during his first transformation, but he has it back on when he is seen in Wolf Man form, running through the woods), further indicating that the footage was hastily inserted without being properly thought through.

The decision to show the Wolf Man clearly appears to have beena last minute one. There is little footage of the monster (which inevitably disappoints younger viewers), some of which is repeated. The monster scenes betray some continuity lapses (Talbot takes off his shirt during his first transformation, but he has it back on when he is seen in Wolf Man form, running through the woods), further indicating that the footage was hastily inserted without being properly thought through.

In spite of all this, THE WOLF MAN manages to survive because it lays out a mythology that seems like authentic, archetypal legend, when in fact it is mostly cinematic invention. Unlike his brethren, Dracula and Frankenstein, the werewolf has no literary classic to serve as the basis of film adaptations; although the lycanthrope, like the vampire, has a history in mythology and superstition, little of it remains in the screen incarnation. European tales of werewolves cast the creatures as voluntary shape-shifters, generally evil sorcerers and thus likely candidates to return from the grave as vampires.

Universal Pictures’ Wolf Man is an altogether different creature, a good but hapless mortal inflicted with a curse. In WERE-WOLF OF LONDON, Hull had played a scientist who was bitten in the line of work, placing him firmly in the tradition of mad scientists established by Robert Louis Stevenson in “The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.” By casting Chaney’s Talbot as an ordinary guy instead of a scientist (he’s no good with theory but enjoys working with his hands), THE WOLF MAN breaks any tenuous connection between the werewolf and Stevenson’s tale: Mr. Hyde, though cunning and evil, was a man, not a beast; even Hull’s hapless Wilfred Glendon was a combination of both. Chaney, on the other hand, plays a character cursed entirely “through no fault of his own,” and his bestial transformation leaves no remnants of his humanity intact.

This transformation perhaps helped the Wolf Man distinguish himself from the dualistic Jekyll and Hyde, allowing him to find his own niche in the public consciousness. Now, instead of a seemingly respectable scientist leading an extremely disreputable double life, the werewolf became a symbol not of Victorian hypocrisy but a more universal one of animal instincts and bestial drives, of hormones causing changes that left the mind incapable of controlling the body. In canine form, Lawrence Talbot had no human cunning; he was simply following an irresistible impulse. (It is tempting to read Freudian interpretations into this scenario, but little of THE WOLFMAN deals with sex on any kind of overt level. For that, audiences would have to wait for Hammer to film their version of the legend.)

THE WOLF MAN was such a hit with audiences that he reappeared in several subsequent films. Unfortunately, Universal was running out of ideas by this time, so Lawrence Talbot was doomed to co-star in a series of team-up movies that cast him alongside Universal’s other frightful fiends: FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN (1943), HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1944), and HOUSE OF DRACULA (1945). His last appearance was playing straight man in the 1948 comedy ABBOT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN (which, like the two “House of” movies, teamed him with both Count Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster). None of these is a classic horror film, but FRANKENSTEIN MEETS THE WOLF MAN is good, brainless fun, especially for kids, and the Abbott and Costello movie is actually better than most of the “serious” horror films of the decade.

Thus, the Wolf Man became a classic monster without have a quite great horror film to call his own (rather like Pinhead in the HELLRAISER movies decades later). Still, Lawrence Talbot lives on in the imagination, indelibly etched for eternity, fearful eyes gazing out the window at the full moon, which brings on the inevitable transformation from man into beast: the growing fur, the snarling fangs, and then the howl…

THE WOLF MAN (1941). Directed by George Waggner. Written by Curt Siodmak. Cast: Lon Chaney Jr, Claude Rains, Ralph Bellamy, Patrick Knowles, Bela Lugosi, Maria Ouspenskaya, Evelyn Ankers.

NOTE: Some of the material in this review originally appeared in Imagi-Movies magazine 1:4, copyright 1994. This article is copyright 2008 by Steve Biodrowski.

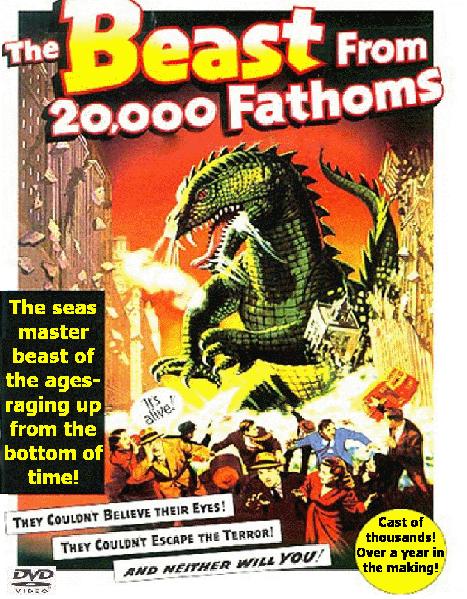

Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953)

The Grand-Daddy of Giant Radioactive Prehistoric Monster Movies.

Ray Harryhausen’s first solo opportunity to supervise special effects (after apprenticing under Willis O’Brien, the technician behind 1933’s KING KONG) is the archetypal model for dozens of sci-fi monster flicks that followed, during the 1950s, and beyond. The story begins with an H-Bomb test, which awakens a predatory dinosaur from a multi-million-year sleep, frozen in icy tundra. A nuclear scientist (Paul Christian) who saw the creature tries to warn the military (in the form of Kenneth Tobey), but no one listens to his story until several boats are sunken, the survivors telling tales of sea serpents. A sympathetic paleontologist (Cecil Kellaway) and his beautiful assistant (Paula Raymond) identify the beast as a rhedosaurus and deduce that its path of destruction is taking it toward New York, where it goes on a rampage. The Beast carries unknown disease that preclude blasting it to pieces (which would only spread the germs), so the nuclear scientist devises a radioactive isotope that will kill the monsters and the bacteria it carries. The lethal antidote is fired (by Lee Van Cleef, later to be a gunslinger in Italian Westerns opposite Clint Eastwood) from atop a roller coaster when the Beast attacks Coney Island, for a fiery and spectacular conclusion.The story of BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS is derivative of KING KONG and, more particularly, O’Brien’s 1925 silent effort THE LOST WORLD (which was based on the novel by Sherlock Holmes-creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle). Like those earlier works, BEAST features a prehistoric monster let loose on a modern city. But those stories had been more or less adventure-fantasies that unearthed their monsters in unexplored, exotic territory. BEAST, with its use of the H-Bomb, added a modern science-fiction edge, coming at a time when audiences really did fear the Bomb, which had the potential, for the first time in recorded history, to bring about the end of recorded history.

Thus, the BEAST becomes a walking metaphor for real fears, a sort of fantasy mirror into which audiences can gaze at something to horrible to contemplate directly. The effect is somewhat muted by the fact that the film ultimately assures us that radiation is okay (a radioactive isotope is used to kill the beast). In this regard, at least, the BEAST’S Japanese clone GOJIRA is considerably more powerful. Nevertheless, BEAST is an effective template from which many other subsequent films were fashioned (including Sony’s misnamed 1998 effort GODZILLA, which far more resembles this film than its namesake).

Unlike many of the movies that worked from its blue print, BEAST has a decent script. The story movies along nicely, with a minimum of downtime (even the obligatory romantic subplot fits in smoothly and unobtrusively). The writers appear to have done their homework, as the scientific jargon rings true and there are few obvious factual howlers. The dialogue is reasonably terse and even displays some clever wit. (At one point, Kellaway chides Tobey for not believing in flying saucers – reminding viewers that Tobey starred in THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD, which featured a flying saucer that brought an alien invader to Earth.)

The cast is made up of competent character actors who bring a decent level of conviction to their roles, spouting off paleontology terms like “Cretaceous” and “Jurassic” as if they know what they are talking about. There is little or none of the flat, cardboard feeling you get from similar films from the era, which tended to be filled with squared jawed heroes and fainting women.

A former production designer, director Eugene Lourie gets everything possible out of his limited resources, using lighting and camera placement to disguise the low-budget. The film looks atmospheric and moody, not cheap, and the judicious use of stock footage adds a sense of scope to the proceedings.

But of course the real star of the film is the special effects. Harryhausen used stop-motion to bring the titular character to life, but instead of creating a KONG-like fantasy world with the use of glass paintings and miniatures, Harryhausen kept the budget down by relying on “plate photography” of actual locations. (In other words, footage of New York streets, etc., was shot and then projected behind the tabletop miniature where Harryhausen animated the armature puppet of the Beast, one frame at a time.)

Being a dinosaur, the Beast cannot win our hearts in the same way that Kong could. But Harryhausen does invest some personality into the creature. Although fearsome and destructive, the rhedosaurus does not seem malignant; he’s just a creature lost in time, returning to the only home he ever knew. He manages to inspire a certain amount of awe, and you’re actually sorry to see the creature collapse and die at the end.

BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS admirably stands the test of time. Despite its financial restrictions, it is a solid effort that works on all levels. Not a masterpiece, perhaps, but definitely a classic of its genre – and vastly better than the 1998 GODZILLA.

FAVORITE SCENES

The paleontologist who wants to preserve capture and preserve the rhedosaurus descends in a diving bell to search for the creature. When he makes visual comment, his enthusiasm for his discovery blinds him to any danger. He enthusiastically describes the variations between what he expected from fossils and what he is actually seeing (“the dorsal spine is singular, not bi-lateral as we thought”). His final words are “But the most amazing thing is…” – just before the dinosaur’s open mouth lunges for the diving bell.

A New York cop, obviously not one to let monsters rampage through his neighborhood unopposed, walks down the middle of the street like a gunslinger, firing six shots from his revolver into the rampaging Rhedosaurus. Stopping to reload, he looks down at his gun – the hungry dinosaur reaches down and lifts him up in his mouth, flipping his body like a cat swallowing a minnow.

TRIVIA

The inspiration for the screenplay is credited to Ray Bradbury, but it appears that the script was not actually based on his short story. When he was offered the chance to do the effects, Ray Harryhausen showed the script to his old friend Bradbury, who noted that the scene wherein the Beast attacks a lighthouse was similar to his story “The Foghorn.” The rights to the story were purchased in order to avoid any legal problems. Since then, Bradbury has speculated that the screenwriters had read the story and incorporated the scene, whether consciously or not. Harryhausen provided a slightly different version of events at a 2006 screening of the film, stating that, after the script was written, the film’s producer came in with a copy of the Saturday Evening Post (which had published the story) and insisted that the lighthouse scene should be added.

This was the directorial debut of Eugene Lourie, who went on to direct two other movies about reawakened rampaging reptiles: 1959’s THE GIANT BEHEMOTH (a.k.a. THE BEHEMOTH, which, ironically, featured special effects by Harryhausen’s one-time mentor, Willis O’Brien) and 1961’s GORGO.

Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was, according to legend, inspired by THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. After a co-production deal fell through to make a large-scale war movie, he conceived of a Japanese version of BEAST. The result was 1954’s GOJIRA, which was released in the U.S. two years later as GODZILLA, KING OF THE MONSTERS. However, it remains unclear whether the late Tanaka had actually seen BEAST or had merely heard about it.

THE BEAST FROM 20,000 FATHOMS. (1953). Directed by Eugene Lourie. Written by Fred Freiberger and Louis Morheim, “inspired” by the short story “The Foghorn” by Ray Bradbury. Cast: Paul Christian (a.k.a. Paul Hubschmid), Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway, Kenneth Tobey, Donalds Woods, Lee Van Cleef.