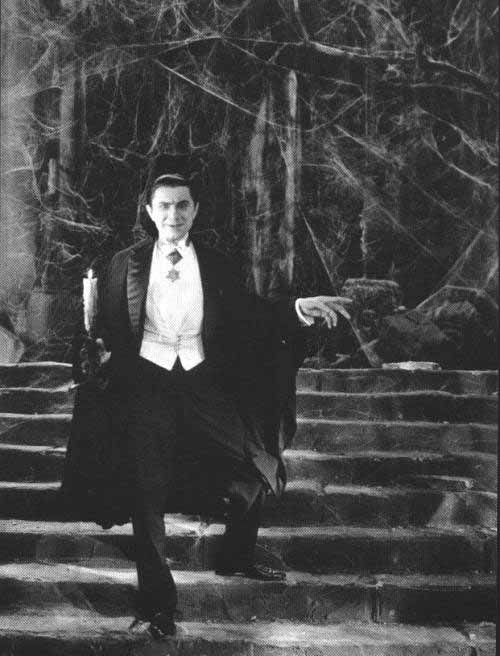

While perusing a brief news bit at The Hollywood Reporter (the announcement of a sequel to the profitable THE PURGE), I happened upon their Iconic Horror Movie Gallery, a post from 2010, featuring images from 16 films. The selection is dubious despite a handful of genuinely iconic titles: there is no ALIEN, for example; but PARANORMAL ACTIVITY and PARANORMAL ACTIVITY 2 make the list, along with HOSTEL, SAW II, THE RING, and BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA. However, what really caught my eye was that, in a post specifically devoted to horror movies, the image of Bela Lugosi as Dracula was clearly from his appearance on stage.

While perusing a brief news bit at The Hollywood Reporter (the announcement of a sequel to the profitable THE PURGE), I happened upon their Iconic Horror Movie Gallery, a post from 2010, featuring images from 16 films. The selection is dubious despite a handful of genuinely iconic titles: there is no ALIEN, for example; but PARANORMAL ACTIVITY and PARANORMAL ACTIVITY 2 make the list, along with HOSTEL, SAW II, THE RING, and BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA. However, what really caught my eye was that, in a post specifically devoted to horror movies, the image of Bela Lugosi as Dracula was clearly from his appearance on stage.

Lugosi’s makeup – the white face, dark lips, and exaggerated brow – is different from his rather more normal appearance in the film. Not only that: although we cannot see the woman’s face clearly, she does not resemble either of the blond victims from the 1931 Universal picture.

Still, it’s a nice image.

Now, if THR could just find a way to get ALIEN, MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH, and THE SHINING into their iconic list.

Tag: Bela Lugosi

Please Allow Me to Introduce Myself: I am … Dracula

You never get a second chance to make a first impression. Movie monsters know that more than anybody. Much of the genre is built upon the suspenseful build-up to the first full revelation of exactly what it is that we the viewers have paid to see and shiver over. Often, that revelation takes the form of a shock-cut and a scream – a shark with a mouthful of teeth lurching from beneath the waters, a masked killer with a knife lurching out of the shadows – but there are other, more subtle introductions as well, times when the monster ingratiates himself into our presence and even our good graces, maintaining the outward forms of civility, much as the satanic narrator of the Rolling Stones “Sympathy for the Devil,” who sings:

Please allow me to introduce myself

I’m a man of wealth and taste

I’ve been around for a long, long year

Stole many a mans soul and faith

[…]

So if you meet me

Have some courtesy

Have some sympathy, and some taste

Use all your well-learned politesse

Or I’ll lay your soul to waste

The shock-form of introduction has its benefits (jump-scares are one of the reasons we go to horror movies), but the more subtle introduction has its place as well, allowing the villain to get into our head and under our skin. Consider, for example, the courtly self-introduction made by the Count in DRACULA (1931).

There have been quite a few memorable introductions in the history of horror movies, none more so than this marvelous entrance by Bela Lugosi in his most famous role, as the regal Transylvanian vampire. The early sound film has a slightly static quality that (perhaps inadvertently) captures the tempo of an ageless immortal who has learned to move at his own pace over the centuries of his undead existence – a facet of his personality that shines like a dark gem in the moonlight as he advances down the stairs, past cobwebs and spiders, and greets his guest Renfield (Dwight Frye) with three simple words, enunciating each individual syllable and pausing dramatically before delivering up his name:

There have been quite a few memorable introductions in the history of horror movies, none more so than this marvelous entrance by Bela Lugosi in his most famous role, as the regal Transylvanian vampire. The early sound film has a slightly static quality that (perhaps inadvertently) captures the tempo of an ageless immortal who has learned to move at his own pace over the centuries of his undead existence – a facet of his personality that shines like a dark gem in the moonlight as he advances down the stairs, past cobwebs and spiders, and greets his guest Renfield (Dwight Frye) with three simple words, enunciating each individual syllable and pausing dramatically before delivering up his name:

“I am … Dra-cu-la.”

You can see the line reading in the embedded video (a clever, fan-made montage) or see the intact sequence by clicking here (embedding disabled, unfortunately). I think you will agree that there is something eerie and unnerving about the way that Dracula refuses to fall into a natural conversational rhythm with Renfield, while simultaneously exuding such formal charm that Renfield is forced to act as if the situation were normal. It is the first hint of the vampire’s ability to dominate mere mortals, even without a display of overt supernatural power – and also the first sign of the vampire seductive nature, presenting an attractive persona that hides the evil nature lurking beneath the skin.

There have been many other great movie monster introductions. I won’t say that none have surpassed Lugosi’s opening salvo, but as someone who saw the film on television at an impressionable age, this is the scene that set the standard by which all others must be judged.

Let’s consider this the first salvo in an on-going, on-again off-again series of memorable opening remarks from movie madmen and monsters. Shall we call it … Please Allow Me to Introduce Myself: Movie Monsters Making a First Impression.

[serialposts]

Richard Gordon, R.I.P.

Moving to New York in 1947, he and his brother met Bela Lugosi, and would later be somewhat involved in his career.

While Alex headed off to Hollywood, Richard Gordon stayed in New York and former Gordon Films, which imported British and other European films for distribution in the American market.

He helped arranged a UK stage tour of DRACULA for Bela Lugosi. When this did not lead to success, Gordon used some connections he had in the British film industry, and came up the story idea for using Lugosi in one of the “Old Mother Riley” comedy films VAMPIRE OVER LONDON (1952, aka MY SON, THE VAMPIRE) .

While successful at distributing others’ films, Richard Gordon still felt the urge to make some of his own, as Alex was doing at AIP. Starting out with the World War II thriller THE DEVIL’S GENERAL (1953) and continuing with UK-lensed crime thrillers, Gordon eventually turned his attention to the genre productions for which he’s best remembered.

Often working without screen credit, he began with THE ELECTRONIC MONSTER (1958, aka ESCAPEMENT), a sci-fi thriller involving mind-control, directed by Mongomery Tully, and starring American actor Rod Cameron and Mary Murphy.

His next project, GRIP OF THE STRANGLER (1958) starred Boris Karloff, as did CORRIDORS OF BLOOD (1958).

FIEND WITHOUT A FACE (1958) was a wild ride, with intially invisible “thought monsters” materializing as stop-motion animated brains, with strangling, snake-like spinal columns, A vivid and unforgettable sight, the creatures have entered sci-fi movie iconography.

FIEND WITHOUT A FACE (1958) was a wild ride, with intially invisible “thought monsters” materializing as stop-motion animated brains, with strangling, snake-like spinal columns, A vivid and unforgettable sight, the creatures have entered sci-fi movie iconography.

Marshall Thompson starred in that film, as well as FIRST MAN INTO SPACE (1959), another sci-fi/horror original.

ISLAND OF TERROR (1966) was directed by Hammer regular Terrence Fisher, and starred Peter Cushing and Edward Judd. The human-devouring “silicates” made memorable monsters in this clastrophobic entry.

THE PROJECTED MAN (1966), starred Bryant Haliday (who would appear in several of Gordon’s films) as the ill-fated scientist Dr. Paul Steiner, victim of a matter transporter gone wrong.

THE PROJECTED MAN (1966), starred Bryant Haliday (who would appear in several of Gordon’s films) as the ill-fated scientist Dr. Paul Steiner, victim of a matter transporter gone wrong.

Other genre offerings include DEVIL DOLL (1964), CURSE OF THE VOODOO (1965), NAKED EVIL (1966), BIZZARE (1970), TOWER OF EVIL (1972, aka HORROR OF SNAPE ISLAND), and HORROR HOSPITAL (1973, aka COMPUTER KILLERS).

In 1978 he produced the remake of THE CAT AND THE CANARY (1978), which starred Honor Blackman, Edward Fox, Wilfred Hyde-White, Olivia Hussey, Carol Lynley, and Michael Callan.

HORROR PLANET (1981 aka INSEMINOID ) was directed by Norman J. Warren and starred Judy Geeson, Robin Clarke, and Stephanie Beacham. It was a particularly gruesome (for the time) low-budget take on ALIEN, filmed in actual caves in England, which add to the oppressive atmosphere. Not actually a good film, but still with some effective moments. The premise itself, of forced alien reproduction, is taken to an unsettling level, as suggested on the poster (right).

HORROR PLANET (1981 aka INSEMINOID ) was directed by Norman J. Warren and starred Judy Geeson, Robin Clarke, and Stephanie Beacham. It was a particularly gruesome (for the time) low-budget take on ALIEN, filmed in actual caves in England, which add to the oppressive atmosphere. Not actually a good film, but still with some effective moments. The premise itself, of forced alien reproduction, is taken to an unsettling level, as suggested on the poster (right).

In recent years Richard Gordon stayed active, writing good-natured letters correcting genre magazine articles, and sharing his recollections of films, filmmakers and actors. He appeared at a number of Horror Movie conventions, recorded commentaries for DVDs, and became something of a fan favorite among those with fond memories of 1950’s-80’s cine fantastique.

Warner Brothers to release Karloff & Lugosi Horror Classics DVD Box Set

Warner Brothers has announced that it will release a DVD box set containing four films featuring Boris Karloff (FRANKENSTEIN) and/or Bela Lugosi (DRACULA), the two greatest stars of classic horror films from the early sound era: THE WALKING DEAD, FRANKENSTEIN 1970, YOU’LL FIND OUT, and ZOMBIES ON BROADWAY. It may be a bit generous to term any of the included titles “classics,” but they are fondly remembered by fans who saw them as children on “Monster Chiller Horror Theatre” or whatever the local TV equivalent was.

I have a particular fondness for YOU’LL FIND OUT, a haunted house spoof in which Karloff, Lugosi, and Peter Lorre co-star with band leader Kay Kaiser. The musical sequences do go on a bit, but the film gives the three horror stars ample opportunity to spoof their bogeyman image; in fact, more than the later Universal Studios “Monster Rallies” (HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN, HOUSE OF DRACULA), YOU’LL FIND OUT is a good showcase for audiences to see an ensemble of their favorite horror icons.

The set is scheduled for an October 6 release, with a suggested price of $26.98.

Here is the press release:

KARLOFF & LUGOSI HORROR CLASSICS

The Walking Dead! Frankenstein-1970!

You’ll Find Out! Zombies on Broadway!

OCTOBER 6 FROM WARNER HOME VIDEO

Burbank, Calif., June 15, 2009 – Horror fans will again be screaming this Halloween when Warner Home Video debuts the Karloff & Lugosi Horror Classics October 6 — four frightfully fun horror classics all in one collection and on DVD for the first time. Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, iconic horror actors best known for creating the screen’s original Frankenstein and Dracula characters, star here in other roles in The Walking Dead, Frankenstein-1970, You’ll Find Out and Zombies on Broadway. The 2-disc set will be available for $26.98 SRP.

The Walking Dead (1936)

The Walking Dead is a unique blend of cinematic horror and the classic Warner Bros. gangster stylings. This long-admired cult favorite stars Boris Karloff, who gives an outstanding performance as John Ellman, an ex-con framed for murder who’s sentenced to the electric chair. When Ellman is brought back to life through the miracles of science, his only task is to seek revenge against those responsible for his death. Michael Curtiz (Casablanca) directs this eerie tale.

Special Feature:

–Commentary by historian Greg Mank

Frankenstein-1970 (1958)

Nearly twenty years after his final appearance as the Frankenstein monster in Son of Frankenstein, Boris Karloff returned to the screen in a new film derived from the Mary Shelley story that first catapulted him to stardom. In this 1958 horror classic, Karloff appears in the role of Dr. Victor Frankenstein, a descendent of the original doctor, whose depleted fortune forces him to grant a film crew access to the family castle to shoot a horror flick. It’s not all bad, though, since he now has a supply of fresh body parts ready for harvesting.

Special Feature:

–Commentary by historians Charlotte Austin and Tom Weaver

You’ll Find Out (1940)

Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi and Peter Lorre poke fun at their horror-genre personas in this wacky 1940 RKO mix of music, murder and mirth. The plot finds the trio of horror legends leaving a trail of terror and laughs along the way, as they plan a murder in order to nab a young heiress’ inheritance in a spooky, spoofy haunted house tale. The film was one of several hits of the era featuring the music and merriment of the then popular Kay Kyser and his band. The film’s original song, “I’d Know You Anywhere” was Oscar® nominated.

Zombies on Broadway (1945)

The emphasis is equally spread between horror and hi-jinx in this wacky RKO production that has endeared itself to generations of die-hard Lugosi fans. Here, Bela Lugosi stars as mad scientist Dr. Paul Renault who ends up with more than he bargained for when he encounters

two inept Broadway press agents (Alan Carney and Wally Brown) looking for a real-life zombie to use for a publicity stunt in promoting a new nightclub.

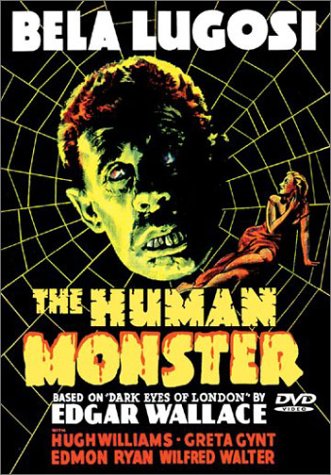

The Human Monster (1940) – Retrospective Review

Based on a novel by Edgar Wallace (titled DARK EYES OF LONDON, as was the film itself in its native England), this is actually more of a crime drama than a horror film. Lugosi stars as “Dr. Orloff,” who runs a lucrative scam, insuring people and then bumping them off to collect the money. A young C.I.D. detective (Hugh Williams) is assigned to figure out why dead bodies keep turning up in the Thames; he is assisted by a Chicago police officer, who gets roped into the case for little reason other than that he happens to be on hand (having just delivered a fugitive to Scotland Yard. The trail leads to a home for the blind, presided over by a Mr. Dearborn, one of many beneficiaries of the publicly generous and respectable Dr. Orloff. Things get complicated when Orloff’s latest victim turns out to have a daughter; the police get her to cooperate, going undercover to expose the doctor’s scam. But (in a plot development reminiscent of Robert Louis Stevenson’s DR. JEKYLL AND MR HYDE), the doctor mysteriously disappears, despite a nation-wide manhunt. Where could he be hiding?

Based on a novel by Edgar Wallace (titled DARK EYES OF LONDON, as was the film itself in its native England), this is actually more of a crime drama than a horror film. Lugosi stars as “Dr. Orloff,” who runs a lucrative scam, insuring people and then bumping them off to collect the money. A young C.I.D. detective (Hugh Williams) is assigned to figure out why dead bodies keep turning up in the Thames; he is assisted by a Chicago police officer, who gets roped into the case for little reason other than that he happens to be on hand (having just delivered a fugitive to Scotland Yard. The trail leads to a home for the blind, presided over by a Mr. Dearborn, one of many beneficiaries of the publicly generous and respectable Dr. Orloff. Things get complicated when Orloff’s latest victim turns out to have a daughter; the police get her to cooperate, going undercover to expose the doctor’s scam. But (in a plot development reminiscent of Robert Louis Stevenson’s DR. JEKYLL AND MR HYDE), the doctor mysteriously disappears, despite a nation-wide manhunt. Where could he be hiding?

As the synopsis reveals, the plot of THE HUMAN MONSTER has no monster, nor much of what one associates with the horror genre. Lugosi’s doctor is given a few lines implying that he is a “mad doctor” (not merely a criminal one), and in one excruciatingly cruel scene, he uses some electrical gizmo to destroy the hearing of a blind-mute violinist — in order to prevent him from overhearing anything he could write about to the police. The blind residents at Dearborn’s home shuffle about like zombies, staring into space. The most prominent of these, Orloff’s hulking homicidal assistant named Jake, wears a bulked up Frankenstein-type costume and has pointed bat-like ears (along with blind eyes) to make him look monstrous as he carries out Orloff’s fiendish schemes (which, it eventually turns out, include drowning people in a vat and then dumping them into the Thames, located conveniently close to Dearborn’s building).

Still, the foggy atmosphere and moody photography lend a darkly horrific air to the proceedings, and Jake’s stalking of his victims (particularly the leading lady) still conveys an authentic chill. The plot is a bit creaky, but there is a certain charm to the film: it hits the obvious notes but hits them well. For example, the brash American cop is not as bright as his English counterpart, but he is good to have around when it comes time to break down doors and start shooting.

Typically, Lugosi does a fine job as a two-faced villain, seemingly innocent to the world at large while indulging in some first-class mugging when showing his sinister side. Sometimes, he goes over the top (e.g., he overreacts way too much when learning that his next intended victim has a next of kin who presumably could lay claim to the insurance policy), but overall he does an excellent job.

Though far from a masterpiece, THE HUMAN MONSTER is worthwhile viewing for anyone interested in old-time mystery-thrillers. For Lugosi fans, it is a chance to see the talented actor given a starring role that stretches his talent, in a film that (while far from lavish) boasts a stronger script and better production values than most of the films he would appear in for the rest of his (mostly disappointing) career.

DVD DETAILS

Alpha Video’s discount DVD release is a bare-bones presentation, made from a print that is not in the best of shape. The image is reasonably good, but the sound is weak, making it hard to understand the dialogue unless you turn the volume way up. There are no bonus features.

TRIVIA

This was the first film to receive the British Censor’s relatively new “H for Horrific” certificate, which limited the film’s audience to adults.

THE HUMAN MONSTER (a.k.a. DARK EYES OVER LONDON, 1940). Directed by Walter Summers. Written by John Argyle, Patrick Kirwan, Walter Summers, based on the novel “Dark Eyes of London” by Edgar Wallace; additional dialogue by Jan Van Lusil. Cast: Bela Lugosi, Hugh Williams, Greta Gynt, Edmon Ryan, Wilfred Walter, Alexander Field.

The Raven (1935) – Retrospective Horror Film & DVD Review

The 1935 pairing of horror stars Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff is still enjoyably over-the-top entertainment.

With the advances in Video on Demand, including services like Amazon.com and Netflix that allow you to watch movies on your TV anytime you like without having to own them, my days of purchasing DVDs are rapidly dwindling. However, I still cannot resist a bargain, and I have a fondness for box sets that package together multiple titles for one low price. Purists complain that the bit-rate on these discs (which save money by squeezing in two films per side) results in reduced quality, but generally I have fond them to be worth the money. One of my favorites is “Bela Lugosi” DVD collection from 2005, which is a must-have for fans of classic horror. The package offers five films (each just a tad over 60 minutes) on two sides of a single disc, with some nice box cover art but almost no bonus features (just a trailer or two).

With the advances in Video on Demand, including services like Amazon.com and Netflix that allow you to watch movies on your TV anytime you like without having to own them, my days of purchasing DVDs are rapidly dwindling. However, I still cannot resist a bargain, and I have a fondness for box sets that package together multiple titles for one low price. Purists complain that the bit-rate on these discs (which save money by squeezing in two films per side) results in reduced quality, but generally I have fond them to be worth the money. One of my favorites is “Bela Lugosi” DVD collection from 2005, which is a must-have for fans of classic horror. The package offers five films (each just a tad over 60 minutes) on two sides of a single disc, with some nice box cover art but almost no bonus features (just a trailer or two).

The highlight of the set is 1934’s THE BLACK CAT, but THE RAVEN (1935) remains a personal favorite, because it gives Lugosi an opportunity to outshine his co-star Boris Karloff (even though Karloff gets top billing). THE RAVEN is the second of three films that Universal Pictures made as a vehicle to co-star Karloff and Lugosi (the first was THE BLACK CAT; the third was THE INVISIBLE RAY). The two had more or less equal roles in BLACK CAT, but Lugosi is clearly the lead in THE RAVEN; Karloff’s character doesn’t even enter until fifteen minutes into the running time (approximately one-quarter of the short film).

THE RAVEN is not quite as good as I remembered, mostly because it is way, way over the top. Lugosi was a stage actor who never got out of the habit of projecting his performance as if he were trying to reach viewers in the back rows of the theatre; on screen, the result can seem quite hammy. Nevertheless, his out-of-control style ultimately works, especially in the latter scenes when the character is past all retrains and thoroughly enjoying the evil he is perpetrating.

The story is about a Dr. Richard Vollin, a great surgeon who has retired to do research and to work on his private obsession, which is collecting –and creating — Poe memorabilia. He brags to a museum representative early on that he has created many of the torture devices that Poe described in his stories (such as the knife-edged pendulum from “The Pit and the Pendulum”). Vollin is called out of retirement to save the life of a young woman, who has been in a car accident. He falls in love with his patient, and begins his descent into madness, calling himself “a god…with the taint of human emotion.”

As Vollin explains it, he renders a service to mankind, but in order to perform that service, his hand must be steady and his mind unclouded by emotions that torture him. When it becomes clear that his patient does not return his love, Vollin’s only solution is seek a truly bizarre form of catharsis: torturing everyone who stands in the way of his frustrated consummation.

He is abetted in this by Edward Bateman (Karloff), an escaped prisoner who once put a torch in the face of a guard during a bank heist. Bateman comes to Vollin looking for a new face so that he can hide from the police. Despite his criminal background, Bateman his a sympathetic figure. Unlike Vollin, who is upper-class, rich, and decadent, Bateman is a working class man obviously driven by circumstances, including not only his economic deprivation but his looks.

“May if a man looks ugly, he does ugly things,” he tells Vollin, who replies in rapt amazement, “You are saying something profound.”

Vollin performs surgery on Bateman, who wants to put his criminal past behind him, but only to make him even uglier (half his face is paralyzed, a blind eye staring at an awkward angle). “Your monstrous ugliness creates monstrous hate,” Vollin chuckles. “I can use your hate.”

The story comes to a climax when Vollin invites his unsuspecting guests to weekend party. After every one’s fallen asleep, he abducts his patient, her fiance, and her father and puts them into his various torture devices (which also include a room with walls that come together to crush those inside). Unfortunately for Vollin, the rebellious Bateman falls for the girl and rebels…

The film is a little bit of a B-movie, in the sense that the cast and settings are relatively small. A little bit of production value is added by reusing existing sets. (For example, Vollin’s patient is a dancer who performs a piece called “The Spirit of Poe,” which staged on the old opera set from Universal 1925 PHANTOM OF THE OPERA.) Although the setting is contemporary, Vollins’ mansion has a basement that looks like a medieval torture chamber, complete with secret passageways. The supporting cast at the party suffers a bit from comic relief, but the lead players all do a very good job.

Like THE BLACK CAT, THE RAVEN is scored with existing bits of classical music (Lugosi at one point serenades his intended love with an excerpt from Back’s Toccata in D Minor). Lew Landers’ direction is somewhat perfunctory, but the studio production values help overcome the deficiencies, and in any case the real reason to see the film is watch the stars, who are aided and abetted by a script that plays to their strengths. Even if the story is not entirely sophisticated, the screenplay is filled with many memorable lines, and the characterizations, although broad, are a perfect fit for the actors, who admirably fill out the roles, their established personas and acting styles making up for the lack of (unnecessary, in this context) subtle psychological depth.

Lugosi is in his element in this one, playing a larger-than-life embodiment of evil insanity. He is nicely balanced by Karloff, who gives a much more low-key performance as a more believable character. The sparks fly quite effectively in thier uneasy partnership (Vollin blackmails Bateman into helping him by promising to restore his distorted features). Although the film is dated by today’s standards, I suspect it played quite well to its intended audience in the 1930s, the time of the great depression. It must have been fun for struggling Americans to see the wealthy Dr. Vollin portrayed as a raging maniac, while poor Bateman is reluctantly enlisted into aiding his evil plans, and there certainly was a grim satisfaction in seeing Bateman turn the tables at the end.

THE RAVEN clearly is not a faithful adaptation of its source material. But it is clearly inspired by by ideas lifted from Poe, particularly the concept of genius and madness co-existing in the same person, who insists on his sanity even while his murderous actions prove him to by quite insane. There is also the concept of a sensitive intellect being tortured by the lass of a great love — although in Poe’s eponymous poem, “the lost Lenore” is dead, not engaged to someone else.

In the end, the film version of THE RAVEN is a Hollywood concoction, pieced together to provide a vehicle for Lugosi and Karloff to duel it out on screen (an element enhanced for modern viewers by our awareness, courtesy of the film ED WOOD, of the competition between the two actors). On this level it thorougly succeeds, earning a sort of “limited” classic status. It is no masterpiece (unlike THE BLACK CAT), but it is an enduring entertainment, especially for Lugosi fans. Other viewers may find the film over-the-top, almost to the point of camp, but this is not the sort of film you need to take seriously in order to enjoy it. Just sit back and go along for the ride.

I mean, you’ve got to love a film wherein the villain chortles, “I tear torture out of myself by torturing you!” Or triumphantly proclaims at the climax, “Poe, you are avenged!”

THE RAVEN(1935). Directed by Lew Landers. Screenplay by David Boehm, inspired by the poem by Edgar Allan Poe. Cast: Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, Lester Matthews, Irene Ware, Samuel S. Hinds, Spencer Charters. Inez Courtney, Ian Wolfe, Maidel Turner.

Copyright 2005 Steve Biodrowski. This version has been slightly updated.

Dracula (1931)

This 1931 adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, by way of the play be Hamilton Deane and John Balderston, is one of those films that qualifies as a classic despite numerous flaws that prevent it from being a masterpiece. In many ways, this is the real starting point of the horror genre in cinema: the silent era had seen Expressionist movement in Germany that produced THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920) and NOSFERATU (1922), and America had produced mystery-thrillers like THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), but this early talkie was the first ever to be designated by the term “horror move.”

This 1931 adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, by way of the play be Hamilton Deane and John Balderston, is one of those films that qualifies as a classic despite numerous flaws that prevent it from being a masterpiece. In many ways, this is the real starting point of the horror genre in cinema: the silent era had seen Expressionist movement in Germany that produced THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (1920) and NOSFERATU (1922), and America had produced mystery-thrillers like THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA (1925), but this early talkie was the first ever to be designated by the term “horror move.”

As a piece of cinema, DRACULA is sorely lacking in many departments: it is slow-paced, talky, and stagy, and yet its reputation remains secure on the basis of the atmosphere sets and photography, coupled with a trio of excellent performances that defined genre archetypes for generations to come. Weighed in the balance, the strengths still make this worthwhile viewing — an atmospheric artifact from the dawn of screen horror.

THE NOVEL AND THE PLAY

The novel by Bram Stoker is, in its own way, a flawed masterpiece — over-long, over-written, and overly populated with under-developed characters. Its strength lies in the way it presents a basic, almost fairy tale story of Good and Evil so that all the blood-and-thunder excitement of a conventional pot-boiler is intact, while at the same time the text is open to a wide range of rich interpretations.

In the novel, young solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to settle the details of a land deal with Count Dracula, a courtly host who turns out to be an ancient vampire intent on spreading his domain beyond his exhausted realm, reaching into the modern world of England, which is teaming with young life and fresh blood. Dracula imprisons Harker in the castle with his three vampire brides and heads off on his journey, but Harker manages to escape. On an ocean voyage to England, Dracula kills everyone on board the vessel, which crashes onto the shore at Whitby Harbor. Soon thereafter, Jonathan’s fiancée, Mina, notes that her friend Lucy Westenra is sleepwalking and showing signs of anemia. One of Lucy’s three suitors, Dr. John Seward, calls in his old professor, Dr. Van Helsing, to consult on her case. The old Dutchman eventually determines that she has been inflicted by a vampire. Lucy succumbs to the vampire’s bite and returns from the grave as one of the undead, attacking young children, but Van Helsing teaches her fiancé, Arthur Holmwood to drive a stake through her chest, putting her soul to rest. Mina goes to Europe to rescue Jonathan, who has turned up in a hospital with a case of amnesia. When they return, Jonathan’s journal helps Van Helsing determine that the vampire who attacked Lucy is in fact Dracula. They begin searching London to destroy the coffins, filled with his native soil, that Dracula has brought with him from Transylvania. One of Dr. Seward’s mental patients, Renfield — a lunatic who eats live insects in the hope of extending his own life — comes to worship Dracula as a sort of Dark Messiah, and aids the vampire in sneaking into Seward’s sanitarium. With no refuge left, Dracula heads back to his castle, but first he attacks Mina and forces her to drink his blood, tainting her so that she will become a vampire upon her death. Van Helsing leads the men to Transylvania and beheads the Count’s vampire brides. In a thrilling horse race, the Englishmen catch up with a band of gypsies racing with the Count’s coffin back to the castle. Jonathan and American adventurer Quincy Morris impale and behead Dracula, but the gypsies mortally wound Morris, who has just enough time before expiring to see that Mina has recovered from the vampire’s taint.

In the novel, young solicitor Jonathan Harker travels to Transylvania to settle the details of a land deal with Count Dracula, a courtly host who turns out to be an ancient vampire intent on spreading his domain beyond his exhausted realm, reaching into the modern world of England, which is teaming with young life and fresh blood. Dracula imprisons Harker in the castle with his three vampire brides and heads off on his journey, but Harker manages to escape. On an ocean voyage to England, Dracula kills everyone on board the vessel, which crashes onto the shore at Whitby Harbor. Soon thereafter, Jonathan’s fiancée, Mina, notes that her friend Lucy Westenra is sleepwalking and showing signs of anemia. One of Lucy’s three suitors, Dr. John Seward, calls in his old professor, Dr. Van Helsing, to consult on her case. The old Dutchman eventually determines that she has been inflicted by a vampire. Lucy succumbs to the vampire’s bite and returns from the grave as one of the undead, attacking young children, but Van Helsing teaches her fiancé, Arthur Holmwood to drive a stake through her chest, putting her soul to rest. Mina goes to Europe to rescue Jonathan, who has turned up in a hospital with a case of amnesia. When they return, Jonathan’s journal helps Van Helsing determine that the vampire who attacked Lucy is in fact Dracula. They begin searching London to destroy the coffins, filled with his native soil, that Dracula has brought with him from Transylvania. One of Dr. Seward’s mental patients, Renfield — a lunatic who eats live insects in the hope of extending his own life — comes to worship Dracula as a sort of Dark Messiah, and aids the vampire in sneaking into Seward’s sanitarium. With no refuge left, Dracula heads back to his castle, but first he attacks Mina and forces her to drink his blood, tainting her so that she will become a vampire upon her death. Van Helsing leads the men to Transylvania and beheads the Count’s vampire brides. In a thrilling horse race, the Englishmen catch up with a band of gypsies racing with the Count’s coffin back to the castle. Jonathan and American adventurer Quincy Morris impale and behead Dracula, but the gypsies mortally wound Morris, who has just enough time before expiring to see that Mina has recovered from the vampire’s taint.

One of the great things about Stoker’s novel is the way it uses everyday detail to make its story believable. Dracula is an ancient monster who comes to modern day London, where he is defeated not just by crosses and garlic but by diligent legwork as the Englishmen search records, legal documents, and manifests to pinpoint his lairs, destroying them one by one until the monster has no choice but retreat to safer territory.

Although the characterizations are relatively simple, they are memorable. Dracula is something of an enigma, a courtly gentleman who also shows signs of animal atavism (as Leonard Wolf pointed out in A DREAM OF DRACULA, the ancient monster rather than the corrupt continental is the true villain of the book). After his character is established in the opening chapters in Castle Dracula, he is mostly a background presence for the rest of the story, which unravels like a mystery. The young men are mostly just virtuous heroes. Mina is to some extent a damsel in distress, although she is clearly smarter and more resourceful than the men. Renfield is a memorably pathetic figure who shifts between madness and sanity, plagued by the moral problem of his allegiance to the vampire. And Van Helsing establishes for all time the figure of the knowing scientist-father figure who will defeat the monster; although there is little depth, he remains impressive — a worthy foe capable of leading the others in the effort to route the seemingly all-powerful Count.

The book is long-winded and occasionally bathetic — it could have benefited from some judicious pruning — but the highlights outshine the lowlights. The opening chapters in the castle are excellent, as are the concluding ones during the chase to Transylvania. In between there is too much hand-wringing from the virtuous characters, who lament over the terrible fate visited on them in spite of their virtue, but there are numerous memorable scenes that keep the story involving, such as the staking of Lucy and Dracula’s assault on Mina.

With its titular character sneaking into bedrooms to exchange bodily fluids, the novel is open to a wide range of Freudian interpretation, no doubt far beyond the scope of what Stoker intended. These dark undercurrents of sexuality, sadomasochism, and Satanism (the Count is clearly intended as a kind of anti-Christ figure) make the book fascinating reading, in spite of the occasional lapses in storytelling.

The play by Hamilton Dean and John Balderston had to jettison much of the novel’s text, simply to fit the story into the confines of the stage. The early section in Transylvania is gone, and Dracula’s image is cleaned up so that he can move in polite London society without raising an eyebrow. The character had worn a cloak in the book, but the tie-and-tuxedo image derives from the play, and his cape actually became a major part of the stagecraft, hiding the actor’s descent through a trap door so that Dracula would seem to disappear from the stage when two humans grabbed the cape — only to find it empty.

THE FILM

When the play was a hit on Broadway in the 1920s, director Todd Browning tried to interest Universal Pictures in purchasing the film rights. When Universal declined, Browning crafted instead crafted a pastiche at MGM, called LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT, with silent film star Lon Chaney as a detective who disguises himself as a vampire. A few years later, Universal reconsidered their decision about DRACULA, with the thought of casting Chaney in the title role, hoping to create another starring vehicle for him, along the lines of their previous successful adaptations of Victor Hugo’s THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME and Gaston Leroux’s THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA.

Chaney contracted throat cancer, which ultimately killed him. The lead in DRACULA went to Bela Lugosi, who had starred in the play on Broadway. A native of Hungary who originally learned his English dialogue phonetically, Lugosi was perfect casting for the part: his commanding height, seductive demeanor, and odd verbal cadences perfectly embodied a sense of an immortal character for whom time had little meaning. There was something at once authentic and larger than life in his performance, which enabled him to indelibly etch the public’s image of a screen vampire for decades hence.

Universal’s original plan was to make DRACULA as an elaborate, big-budget adaptation of the book, much as they had with HUNCHBACK and PHANTOM. However, a financial crisis brought on by the Great Depression necessitated that the film be severely telescoped; much of it ended up being a filmed version of the play, although numerous scenes from the book from the book (particularly the beginning in Transylvania) were added back in for the film version.

The result is some sever continuity problems. We only briefly see the vampire Lucy walking in the dark; Van Helsing promises to put a stop to this, but we never see her staked. The early Castle Dracula scenes introduce us to the vampire’s undead brides, but instead of bringing the story full circle as Stoker did, the ending has the Count staked in the basement of Carfax Abbey in England; thus, the forgotten brides are left to prey on Transylvania, instead of being dispatched as they were in the book. Perhaps worst of all, we never know exactly what Renfield is doing to help his “Master,” the Count. (In the book, vampires cannot cross a threshold unless invited by someone inside. It is Renfield who does this, allowing Dracula access to Mina.)

The film also suffers from an excess of restraint. Even by the standards of the day, when it was considered in good taste to suggest horror rather than depict it graphically, DRACULA seems too tame. Some of the best material is described rather than shown. An attendant at Seward’s asylum reads a newspaper account that refers to Lucy’s return from the grave. Mina tells us the Dracula opened a vein in his arm (rather than in his chest, as in the book) and forced her to drink. Renfield recounts his temptation, wherein the Count offered him thousands of “Rats! Rats! Rats!” in exchange for his loyalty and obedience.

There is some compensation. By following the conventions of the play, the film provides an opportunity for Van Helsing and Dracula to confront each other while hiding behind the pretext of polite society. In one memorable moment, Dracula attempts to hypnotize the professor, who seems on the verge of succumbing before regaining his self-control, forcing the frustrated vampire to admit, “Your will is strong.”

Actor Edward Van Sloan is perfect as the professor, a perfect embodiment of knowledge and discipline, without the book’s overwrought Dutch dialect and bumbling manner (which were meant to humanize him). Minus these minor flaws, Van Sloan’s Van Helsing emerges as the archetypal authority figure who must be obeyed because he knows what’s best for your own good even if you’re too skeptical to believe him.

The other standout in the cast is Dwight Frye, who lends a unique maniacal laugh to the character of Renfield. His wild-eyed glee at serving his master helps enliven the later scenes, which tend to lapse into talky theatricality at times, and he even manages to generate a little sympathy for the hapless madman when, as in the book, he dies at the hands of his vampire overlord.

Helen Chandler and David Manners fare less well as the young leads, Mina and Jonathan. They are attractive enough in a conventional way, but they generate little passion together, and they come across as standard issue ingénues. (Manners would fare much better a few years later in THE BLACK CAT, with Lugosi and FRANKENSTEIN’s Boris Karloff.)

By critical consensus, the highlight of the film remains the opening sequence in Transylvania, where matt paintings, a studio back lot, and some magnificent sets create a Gothic world meant to represent the a mythic version of the “Land Beyond the Forest.” The brief coach ride through the mountains is impressive. Even before we get to the castle, the film draws you into its depiction of a foreign world, with a lovely inn where peasants warn the English visitor (in this case, Renfield, replacing Harker, who took the journey in the novel) to wear a cross “For your mother’s sake” and intone the Lord’s Prayer in Hungarian. You get a rich sense that of superstition and the supernatural, evoking a sense of a communal dream for the audience. Everything is strange and yet somehow familiar, like deja vu.

After that, the ride to the castle is delightfully spooky, with a cloaked Count pretending to be an anonymous coach driver and then disappearing, to be replaced by a bat. Lugosi’s initial appearance atop the stairs at Castle Dracula presents us with his famous self-introduction: “I am…Dracula.” Long beat. “I bid you welcome.” A strange sense of dislocation emanates from the exaggerated courtesy delivered amid crumbling rocks, rats (actually possums, meant to represent large rats), and a magnificent spiderweb that completely blocks the staircase.

Soon thereafter, we get another famous line (not from the book): “I never drink…wine.” Then Renfield faints, and Dracula’s brides move in for a taste, but Dracula waves them off, reserving first blood for himself, bringing the opening sequence to a close as the camera fades out.

After this remarkably effective opening, the rest of the film moves in fits and starts. Some build-up leads to a weak payoff (e.g., the shipboard trip from Transylvania cuts away before the Count starts picking off the crew). The comic relief (in the form of an asylum attendant who speaks in an exaggerated Cockney accent) is amusing for younger viewers but tiresome for adults. And the staging of the later scenes leaves something to be desire, as characters tend to stand around and talk a lot instead of doing anything. Fortunately, the film is usually on strong footing whenever Lugosi is on screen: his commanding presence, aided by support from Van Sloan and Frye, holds our attention through the slow parts.

AFTERMATH

Whatever the flaws in DRACULA, the fascinating image of the vampire as a seductive predator, to whom females might willingly succumb, was more than enough to make it a huge hit when it was released in February of 1931 (the advertisements billed it as “The Strangest Love Story Man Has Ever Known”). This represented something of a breakthrough in the United States: up until that time, spooky American mystery-thrillers had always explained away any apparently supernatural phenomenon. To cite two silent films starring Lon Chaney as examples: the Phantom of the Opera turns out to be a disfigured man, not a ghost, and the vampire in LONDON AFTER MIDNIGHT is revealed to be a detective in disguise. (Of the later film, director Todd Browning famous stated that viewers were asked to believe in the horrifying plausible rather than the horrifying impossible, and plausability increased, rather than lessened the thrills.)

Thus DRACULA represented something altogether novel for American audiences, and Universal pictures was quick to exploit the successful new formula. In the days before sequels had become de rigueur, the studio did not follow-up with DRACULA II; instead, the opted to purchase another horror property, FRANKENSTEIN, with the idea of casting Lugosi as the monster. When the actor balked, Boris Karloff got the role, and the rest was history.

Strangely, Universal never did make a proper sequel to DRACULA. After BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN in 1935, they did finally get around to the idea of a new Dracula movie, DARCULA’S DAUGHTER, which was originally planned as a co-starring vehicle for Karloff and Lugosi, with FRANKENSTEIN director James Whale at the helm. Unfortunately, none of the three talented men was involved in the film that was ultimately released under that title in 1936. Apparently, censorship problems in England (a major market for Universal’s horror films) caused the studio to back off their original idea, so the Dracula character was removed from the film. The problem seems to have been the unsavory sexual suggestion inherent in a story about a man who snuck into bedrooms to feast on the blood of supine virgins. Of course, the unintended irony was that, by focusing on a female vampire sucking on female victims, DRACULA’S DAUGHTER wound up loaded with lesbian undertones — a fine example of censorship actually increasing the perversity of a film.

In the 1940s, when Universal was rehashing every horror property from the glorious era in the 1930s, Lon Chaney Jr played the title role in SON OF DRACULA (1943), a contemporary thriller set in America, where the heir to the Dracula throne comes across like a lame metaphor for NAZI Germany — a corrupt aristocrat from Europe come to drain the vitality of the New World. Eventually, Dracula himself re-appeared, this time played by the gaunt Shakespearian actor John Carradine, in the HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN and HOUSE OF DRACULA, both of which also featured Frankenstein’s Monster and the Wolf Man. Lugosi himself finally returned to the role that made him famous in ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET FRANKENSTEIN, a comedy spoof that is actually much better than the two monster rallies that preceded it. Lugosi does a good job of resurrecting the familiar elements of his old performance while at the same time showing that he is in on the joke.

Since then, numerous other companies have made numerous other films starring numerous other actors as the Count — a number far too vast to recount here. But it is worth noting that Universal Pictures returned to their original horror character in 1979, when Frank Langella played the lead in a new, color widescreen version of DRACULA. Like Lugosi, Langella had been a hit in the role on stage, when the old Deane-Balderston play was revived. The new DRACULA benefited from Langella’s mesmerizing performance, excellent production values and a budget that allowed for the story to be developed at fuller length; unfortunately, this resulted in some unnecessary scenes that could have been deleted in favor of tighter pacing.

DRACULA EN ESPANOL

As is well known among fans today, two versions of the 1931 DRACULA were filmed: one in English, one in Spanish. Apparently, during the early days of sound filmmaking, it had not occurred to the movie studios that talking pictures could be dubbed into foreign languages, so Universal Pictures hired a separate cast and crew to film a Spanish language version of DRACULA at night, using the same sets were Todd Browning was shooting the Lugosi film during the day.

With the benefit of being able to second guess the Browning film (the crew could watch the rushes and decide what worked and what didn’t), the Spanish language version has earned the reputation of being cinematically superior to its more famous English-speaking brother. There is no doubt that the film features a more inventive use of camera angles to tell the story, but the Spanish DRACULA suffers from some histrionic performances that make it even more of a museum piece than the Browning production. After the pleasant shock of seeing a new version of a familiar classic wears off, the Spanish DRACULA can be just as difficult — in fact, more — difficult to sit through.

SEEN TODAY

In an odd way, DRACULA benefits from its degraded reputation. Unlike many classics, which can have difficulty living up to expectations, DRACULA comes across reasonably well — in fact, better than expected — when reviewed today. It is taken for granted that the film is slow, talky, and memorable only for Bela Lugosi’s performance. So it is a pleasant surprise to find that much of the film actually does play well for an audience of eager fans. The first half is startlingly good, filled with delicious atmosphere and melodrama (beautifully captured in glorious black-and-white by Karl Freund’s mobile camera), and even when things slow down later, they never quite grind to a halt.

In an odd way, DRACULA benefits from its degraded reputation. Unlike many classics, which can have difficulty living up to expectations, DRACULA comes across reasonably well — in fact, better than expected — when reviewed today. It is taken for granted that the film is slow, talky, and memorable only for Bela Lugosi’s performance. So it is a pleasant surprise to find that much of the film actually does play well for an audience of eager fans. The first half is startlingly good, filled with delicious atmosphere and melodrama (beautifully captured in glorious black-and-white by Karl Freund’s mobile camera), and even when things slow down later, they never quite grind to a halt.

Certainly, this is the kind of movie that often leaves you waiting for something good to happen; but good moments do occur, just often enough to hold interest. In the final analysis, Todd Browning’s 1931 production of DRACULA may not be a masterpiece, but it is much better than generally regarded, and deserves far more critical latitude than F.W Murnau’s over-rated 1922 silent snoozefest, NOSFERATU.

Copyright 2005 Steve Biodrowski

Cold Flesh, Warm Blood: Hollywood's Hottest Vampires

Once upon a time, vampires were resurrected corpses: ghastly, smelly creatures that crawled back out of their graves and attacked innocent victims with all the seductive charm of ravenous predators, hungry only for the living blood that would warm their cold flesh and sustain their undead existence. Much has changed over the centuries. In literature and cinema, the undead have morphed from mindless blood-drinkers to sophisticated aristocrats to Byronic anti-heroes to misunderstood outsiders; through it all, their sexual charisma has been increasingly emphasized to the point where (as in the recently released TWLIGHT) they are no longer monsters but objects of affection. As with man “innovations,” the audience watching TWLIGHT probably thinks they are seeing something new, but hot-blooded passionate vampires have been around since the dawn of talking films. Below is a rogue’s gallery of the most memorable.

Bela Lugosi as the Count in DRACULA (1931). Lugosi was cinema’s first seductive vampire. Hungarian by birth, the actor exuded Continental charm of the sort guaranteed to leave your average American male feeling inadequate and jealous by comparison. All he had to do was deliver a few lines of dialogue in his mesmerizing cadence, and Lucy Western (Frances Dade) was smitten, dreaming of Castle Dracula in Transylvania. Of course, nothing overtly sexual could be shown in 1931, but that is part of the cinematic appeal of vampirism, with blood-drinking standing in symbolically for other exchanges of bodily fluids. The Count could sneak into a woman’s bedroom – practically into her bed – and in a case of mass denial, audiences and critics could pretend they were watching a horror scene when it was actually ravishment.

Bela Lugosi as the Count in DRACULA (1931). Lugosi was cinema’s first seductive vampire. Hungarian by birth, the actor exuded Continental charm of the sort guaranteed to leave your average American male feeling inadequate and jealous by comparison. All he had to do was deliver a few lines of dialogue in his mesmerizing cadence, and Lucy Western (Frances Dade) was smitten, dreaming of Castle Dracula in Transylvania. Of course, nothing overtly sexual could be shown in 1931, but that is part of the cinematic appeal of vampirism, with blood-drinking standing in symbolically for other exchanges of bodily fluids. The Count could sneak into a woman’s bedroom – practically into her bed – and in a case of mass denial, audiences and critics could pretend they were watching a horror scene when it was actually ravishment.

Christopher Lee as the Count in HORROR OF DRACULA (1958). Twenty-seven years after Lugosi, Christopher Lee redefined the Vampire King in much more physical terms. Gone was the oily charm and much of the mesmeric quality; this Dracula’s advances upon women were much more aggressive and overtly carnal, suggesting an undead rapist from beyond the grave. (True to the fantasy – not the reality – of rape, the women eventually succumb willingly, even if they are ambivalent or reluctant at first.) Lee played the role many times after HORROR OF DRACULA; although the sequels often failed to use the Count in interesting ways, the actor always maintained the not so subtle sexual subtext that made his vampire alluring even while he was dangerous.

Christopher Lee as the Count in HORROR OF DRACULA (1958). Twenty-seven years after Lugosi, Christopher Lee redefined the Vampire King in much more physical terms. Gone was the oily charm and much of the mesmeric quality; this Dracula’s advances upon women were much more aggressive and overtly carnal, suggesting an undead rapist from beyond the grave. (True to the fantasy – not the reality – of rape, the women eventually succumb willingly, even if they are ambivalent or reluctant at first.) Lee played the role many times after HORROR OF DRACULA; although the sequels often failed to use the Count in interesting ways, the actor always maintained the not so subtle sexual subtext that made his vampire alluring even while he was dangerous.

Valerie Gaunt as the Vampire Woman in HORROR OF DRACULA. Female vampires of an earlier era tended to be more sedate and slow-moving. Gaunt’s unnamed vampiress, although briefly seen, was a memorably breath-taking change-of-pace. Buxom and beautiful, she befriends Jonathan Harker by pretending to need his help, then sinks his fangs into him unexpectedly. Her fierce, predatory nature and good looks set the style for numerous female vampires over the next decade: beautiful fatal women whose charms were so alluring that men might willing lose their lives to them.

Valerie Gaunt as the Vampire Woman in HORROR OF DRACULA. Female vampires of an earlier era tended to be more sedate and slow-moving. Gaunt’s unnamed vampiress, although briefly seen, was a memorably breath-taking change-of-pace. Buxom and beautiful, she befriends Jonathan Harker by pretending to need his help, then sinks his fangs into him unexpectedly. Her fierce, predatory nature and good looks set the style for numerous female vampires over the next decade: beautiful fatal women whose charms were so alluring that men might willing lose their lives to them.

Barbara Steele as Princess Asa in BLACK SUNDAY (a.k.a. THE MASK OF SATAN, 1960). Princess Asa was not the first female vampire to play a lead role (that honor goes to DRACULA’S DAUGHTER in 1936), but she is the first one who is truly hot, thanks in no small part to the performance of actress Barbara Steele, who makes the resurrected revenant desirability almost palpable. Burned as a witch, Asa revives centuries later. Still unable to move, she succeeds in luring her first victim to her side using only her seductive charms, most prominently her heaving chest as she lies otherwise immobile on her slab, lusting for the blood that will infuse her with new life. There is a kind of sick almost sadomasochistic edge to this particularly vampire, thanks to her pockmarked face (result of her torture and execution that killed her), and having her literally kiss her victim will still lying in her tomb lends a creepy shudder at the necrophiliac undertones. Thanks to Steele, it is easy to believe that her victim would be swept away by desire and ignore these disturbing undertones.

Barbara Steele as Princess Asa in BLACK SUNDAY (a.k.a. THE MASK OF SATAN, 1960). Princess Asa was not the first female vampire to play a lead role (that honor goes to DRACULA’S DAUGHTER in 1936), but she is the first one who is truly hot, thanks in no small part to the performance of actress Barbara Steele, who makes the resurrected revenant desirability almost palpable. Burned as a witch, Asa revives centuries later. Still unable to move, she succeeds in luring her first victim to her side using only her seductive charms, most prominently her heaving chest as she lies otherwise immobile on her slab, lusting for the blood that will infuse her with new life. There is a kind of sick almost sadomasochistic edge to this particularly vampire, thanks to her pockmarked face (result of her torture and execution that killed her), and having her literally kiss her victim will still lying in her tomb lends a creepy shudder at the necrophiliac undertones. Thanks to Steele, it is easy to believe that her victim would be swept away by desire and ignore these disturbing undertones.

Barbara Shelley in DRACULA, PRINCES OF DARKNESS (1965). In this sequel to HORROR OF DRACULA, Shelley plays a vampire in the model of Valerie Gaunt, but there is a twist: she starts out as a prim Victorian wife before transforming into an infernal seductress. The switch is starling, suggesting that the character’s repressive attitudes were a way of restraining her own hidden desires, which explode free when she becomes a vampire. These desires turn out to be lesbian in nature; she shows no interest in potential male victims, focusing her attentions instead upon her sister-in-law. Shelley was one of the best actresses to play this kind of role: she brings something more to the role than mere good looks – a real sense of hot hidden passions finally boiling to the surface.

Barbara Shelley in DRACULA, PRINCES OF DARKNESS (1965). In this sequel to HORROR OF DRACULA, Shelley plays a vampire in the model of Valerie Gaunt, but there is a twist: she starts out as a prim Victorian wife before transforming into an infernal seductress. The switch is starling, suggesting that the character’s repressive attitudes were a way of restraining her own hidden desires, which explode free when she becomes a vampire. These desires turn out to be lesbian in nature; she shows no interest in potential male victims, focusing her attentions instead upon her sister-in-law. Shelley was one of the best actresses to play this kind of role: she brings something more to the role than mere good looks – a real sense of hot hidden passions finally boiling to the surface.

Jonathan Frid as Barnabas Collins in DARK SHADOWS (1960s soap opera). Frid played Barnabas as a tragic character, cursed with desires he abhored but could not control. In keeping with the soap opera nature of the show, love stories and romantic entanglements were a big part of the plot lines. In particularly, the 100-year-old vampire yearned for his lost love from the time when he was human; conveniently, she was reincarnated (a plot line that would be resued in BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA). Though Barnabas was a reluctant vampire, his approach to women maintained a seductive aura that was enhanced by his tragic nature; the combination appealed to millions of female fans when the show originally aired. Barnabas Collins may be the screen’s first truly Romantic member of the legion of the undead.

Jonathan Frid as Barnabas Collins in DARK SHADOWS (1960s soap opera). Frid played Barnabas as a tragic character, cursed with desires he abhored but could not control. In keeping with the soap opera nature of the show, love stories and romantic entanglements were a big part of the plot lines. In particularly, the 100-year-old vampire yearned for his lost love from the time when he was human; conveniently, she was reincarnated (a plot line that would be resued in BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA). Though Barnabas was a reluctant vampire, his approach to women maintained a seductive aura that was enhanced by his tragic nature; the combination appealed to millions of female fans when the show originally aired. Barnabas Collins may be the screen’s first truly Romantic member of the legion of the undead.

Ingrid Pitt as Carmilla in THE VAMPIRE LOVERS (1970). Looking to inject new blood in the vampire formula, Hammer Films (the company behind HORROR OF DRACULA) decided to make the eroticism even more overt in this adaptation of J. Sheridan LeFanus’ classic novella, Carmilla. Pitt plays the vampire countess not only as an insatiable seductress but also as a passionate lover: when necessary, she effortlessly uses her sex appeal to seduce those who might interfere with her plans, but she also truly wants her intended victim to follow her willingly into the netherworld of vampirism. Carmilla uses her body like a weapon to get what she wants, and Pitt dominates the screen in the role, practically burning up the screen.

Ingrid Pitt as Carmilla in THE VAMPIRE LOVERS (1970). Looking to inject new blood in the vampire formula, Hammer Films (the company behind HORROR OF DRACULA) decided to make the eroticism even more overt in this adaptation of J. Sheridan LeFanus’ classic novella, Carmilla. Pitt plays the vampire countess not only as an insatiable seductress but also as a passionate lover: when necessary, she effortlessly uses her sex appeal to seduce those who might interfere with her plans, but she also truly wants her intended victim to follow her willingly into the netherworld of vampirism. Carmilla uses her body like a weapon to get what she wants, and Pitt dominates the screen in the role, practically burning up the screen.

Robert Tayman as Count Mitterhaus in VAMPIRE CIRCUS (1972). Another vampire variant from Hammer films, this one portrays the undead as members of a circus that comes to town and seduces the local populace. It is all to avenge the death of Count Mitterhaus, who is dispatched in the pre-credits prologue after seducing a school master’s wife. Tayman gives a memorable, albeit truncated performance, as the Count, for whom various carnal appetites are barely distinguishable. “One lust feeds another,” he says, as he switches from blood-drinking to love-making, earning his place in cinema history as the first movie vampire who seems capable of having conventional sex.

Robert Tayman as Count Mitterhaus in VAMPIRE CIRCUS (1972). Another vampire variant from Hammer films, this one portrays the undead as members of a circus that comes to town and seduces the local populace. It is all to avenge the death of Count Mitterhaus, who is dispatched in the pre-credits prologue after seducing a school master’s wife. Tayman gives a memorable, albeit truncated performance, as the Count, for whom various carnal appetites are barely distinguishable. “One lust feeds another,” he says, as he switches from blood-drinking to love-making, earning his place in cinema history as the first movie vampire who seems capable of having conventional sex.

Frank Langella as Dracula in DRACULA (1979). As Dracula, Langella emphasizes the Count’s aristocratic manner and his romantic charm; he is also probably the first actor to make Dracula truly sympathetic. Like Lugosi, he’s the guy you just can’t compete with for the girl’s affections, because you know you are going to lose. The difference is that Langella’s vampire actually seems to admire Lucy (Kate Nelligan) for her strong-willed, independent ways: he’s not so much seducing her as courting her. The consummation, when it comes, is filmed with cloudy laser lights, suggesting a rapturous romantic interlude of mutual satisfaction. Unlike Mitterhaus in VAMPIRE CIRCUS, it is not clear that he has conventional sex, but the way the scene is presented visually, he might as well have. The result is not only sexy but also romantic, in a way that the later BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA could only hope to be.

Frank Langella as Dracula in DRACULA (1979). As Dracula, Langella emphasizes the Count’s aristocratic manner and his romantic charm; he is also probably the first actor to make Dracula truly sympathetic. Like Lugosi, he’s the guy you just can’t compete with for the girl’s affections, because you know you are going to lose. The difference is that Langella’s vampire actually seems to admire Lucy (Kate Nelligan) for her strong-willed, independent ways: he’s not so much seducing her as courting her. The consummation, when it comes, is filmed with cloudy laser lights, suggesting a rapturous romantic interlude of mutual satisfaction. Unlike Mitterhaus in VAMPIRE CIRCUS, it is not clear that he has conventional sex, but the way the scene is presented visually, he might as well have. The result is not only sexy but also romantic, in a way that the later BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA could only hope to be.

Anne Parillaud as Marie in INNOCENT BLOOD (1992). This disappointing horror-comedy from director John Landis features Parillaud (who came to fame as the original LE FEMME NIKITA) as a vampire who kills only murderers. She teams up with a cop (Anthony LaPaglia), and the two take on the Mob, but complications arise when one of her victims becomes a vampire and starts turning other criminals into vampires as well. The film’s main appeal is Parillaud, who makes for a slim and sexy vampire. The highligh is her bedroom seen with LaPaglia, whose cop is so frightened of her superhuman abilities that he can rise to the occasion only if she is in handcuffs (which she almost immediately breaks anyway). It’s like a fun, teasing variation on the whacked-out misogynistic paranoid of Paul Schrader’s CAT PEOPLE (1982), made by a director who doesn’t think women need to be locked up in cages to protect men from their predatory ways.

Anne Parillaud as Marie in INNOCENT BLOOD (1992). This disappointing horror-comedy from director John Landis features Parillaud (who came to fame as the original LE FEMME NIKITA) as a vampire who kills only murderers. She teams up with a cop (Anthony LaPaglia), and the two take on the Mob, but complications arise when one of her victims becomes a vampire and starts turning other criminals into vampires as well. The film’s main appeal is Parillaud, who makes for a slim and sexy vampire. The highligh is her bedroom seen with LaPaglia, whose cop is so frightened of her superhuman abilities that he can rise to the occasion only if she is in handcuffs (which she almost immediately breaks anyway). It’s like a fun, teasing variation on the whacked-out misogynistic paranoid of Paul Schrader’s CAT PEOPLE (1982), made by a director who doesn’t think women need to be locked up in cages to protect men from their predatory ways.

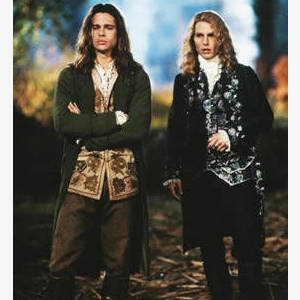

Brad Pitt and/or Tom Cruise in INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE (1994). Neil Jordan’s film comes nowhere near achieving the full brilliance of Anne Rice’s novel, but it does capture some of the essence, particularly the erotic though not necessarily sexual nature of vampires. In this telling, the undead’s sexual apetites have been completely subsumed into blood-drinking, which creates as much rapturous joy as any conventional orgasm. Pitt and Cruise make for a handsome pair of homo-erotic immortals, and the film works overtime to keep passions so high that the predatory nature of their characters never interferes with the female audience’s urge to swoon over their beauty.

Brad Pitt and/or Tom Cruise in INTERVIEW WITH THE VAMPIRE (1994). Neil Jordan’s film comes nowhere near achieving the full brilliance of Anne Rice’s novel, but it does capture some of the essence, particularly the erotic though not necessarily sexual nature of vampires. In this telling, the undead’s sexual apetites have been completely subsumed into blood-drinking, which creates as much rapturous joy as any conventional orgasm. Pitt and Cruise make for a handsome pair of homo-erotic immortals, and the film works overtime to keep passions so high that the predatory nature of their characters never interferes with the female audience’s urge to swoon over their beauty.

There have not been many memorably hot vampires since INTERVIEW. Series like BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER, ANGEL, and MOONLIGHT keep the tradition alive, but the emphasis is as much on angst as attraction – a trend brought to full fruition in TWILIGHT, where the whole point is the rapturous ecstasy of abstinence, lusting for a hot-blooded vampire who dare not draw too near, for fear that his bestial nature will take over. This modern approach to vampirism has its appeal, but it burns a few degress cooler than earlier generations of vampires, for whom blood-drinking was an all-purpose symbol for breaking taboos. Elicit pleasures burns much hotter when they are forbidden by feelings of guilt and sin. Edward Cullen’s self-restraint may be admirable, but for searing passionate can it really match the erotic allure of succumbing to the temptation of a demon lover who is truly demonic?

Black Cat, The (1934)

No monsters but lots of atmosphere, this is a classic of the genre.

Eschewing many standard genre elements of its era, THE BLACK CAT is barely a horror film in the traditional sense, and it has even less to do with Poe than 1932’s MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE (which had also starred Lugosi). Nevertheless, this original scenario concocted by director Ulmer and writer Ruric is more than strong enough to earn this film a berth among the 100 Best Horror Films Ever Made.

Set mostly in a “House of Doom,” (the film’s title in England), which was built by an architect on the ruins of the fortress he sold out to the enemy during the First World War, the film has a very contemporary air, thanks to its (for the time) futuristic set design. Although not much actually happens, a subtle aura of perversity imbues the abode with an intangible but palpable horror, much like Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.” (The overseas title hints at this connection.)

Conceiving the picture in an effort to capitalize on the success of DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN (both 1931), Universal Pictures pitted their reigning Kings of Horror, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, against each other in a battle of the Terror Titans. The story is basically a revenge tale, with Lugosi as Vitus Verdegast, returning to avenge himself on the architect (Karloff) who betrayed him and countless others during the war, and then married Verdegast’s wife (and later his daughter, too!) while Verdegast was being tortured in a prisoner of war camp.

Karloff, whose most famous horror role (as Frankenstein’s monster) was laced with patho, is excellently sinister here as the unrepentant and totally evil Satanist (who keeps his dead wives on display in glass cases in his basement). David Manners (an old hand at this kind of thing, since appearing in DRACULA and THE MUMMY) and Jaqueline Wells provide solid support as the innocent, honeymooning couple caught up in the conflict.

But the real coup lies in casting Lugosi as the nominal hero, which yields wonderful results, because his character is as unhinged as the villain. Locked in mortal combat, the only thing that separates him from his adversary is that he still has some concern for the innocent victims caught in the crossfire. Other than that, we are asked to identify with him, even as he finally loses all restraint and flays his tormentor alive!

Some elements are thrown in more or less gratuitously. Poe`s feline shows up long enough to justify the film’s American title and to help explain Verdegast’s delayed vengeance (his phobic reaction prevents him from killing his enemy at a crucial point). Diabolism and mysticism are thrown in to secure the film’s place in the genre (Karloff’s character is also a practising Satanist.)

But mostly the film is about the mortal struggle of two characters past all normal human boundaries of pain and suffering. The real horror is that of souls gone dead because of real-life atrocities of World War One. (At one point, when the yound lead is unable to phone for help, Karloff cackles, “Did you hear that, Vitus? The phone is dead! Even the phone is dead!”) This is probably the first film to make a direct connection between the real horrors of that war and the imaginary horrors it inspired on the silver screen.

There are some flaws, many apparently due to post-production tinkering. In several cases, lines have obviously been dubbed to help the audience understand what’s happening. In some cases, long shots that were intended to play without dialogue have voices issuing from mouths that are not moving. In two brief cases, we hear different actors’ voices coming from Karloff or Lugosi.

Also, the film’s almost operatic approach sometimes seems a bit heavy-handed. The music score (patched together from classical pieces) underlines the action with no pretense of subtlety, blaring ominously whenever Karloff enters a scene. There’s even an amusing moment in the second half of the film when two officials show up to ask some questions: even before they open their mouths, the music lets us know they’re on hand to provide some comic relief (they get into a pointless argument about which of their hometowns the honeymooning couple should visit).

But these minor flaws are trivial compared to the overall effectiveness. With no monster and little conventional suspense, this is nevertheless an extremely unusual and effective horror film that seeks to disturb on a deeper level. The music score may be a bit overemphatic for today’s viewers; otherwise, director Edgar G. Ulmer`s film is a perverse classic, tinged with hints of taboo subjects (necrophilia, incest) that still evoke a chill.

THE BLACK CAT (a.k.a. HOUSE OF DOOM, 1934). Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer. Screenplay by Peter Ruric; screen story by Ruric & Ulmer, suggested by the Edgar Allan Poe tale. Cast: Boris Karloff, Bela Lugosi, David Manners, Jacqueline Wells, Lucille Lund.

The Wolf Man (1941)

A classic despite its flaws

A classic despite its flaws

This 1941 film is widely considered to be one of the classics of the horror genre, because it introduced the world to one of the most famous movie monsters of all time: Lawrence Talbot (Lon Chaney, Jr.), an innocent man bitten by a wolf, who then succumbs to the curse of lycanthropy. After Count Dracula and Baron Frankenstein, THE WOLF MAN probably ranks third in the pantheon of Universal Pictures’ famous movie monsters. Unfortunately, the film itself is a classic without being an actual masterpiece. It is glossy and atmospheric, but it lacks the imaginative impact and artistic sensibilities of DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN (both made ten years earlier), relying on solid studio production values (sets and photography), plus its fine cast, to compensate for director George Waggner’s competent but not necessarily inspired handling of the material.

THE PLOT

The story follows Talbot (Chaney) as he returns to his ancestral home after a stay in America. He escorts two ladies to a gypsy camp where they have the fortunes read, but the fortune teller, Bela (played by DRACULA’s Bela Lugosi) is disturbed when he sees a pentagram in the hand of one of the girls – a sign that she will be the werewolf’s next victim. On the way home, the trio are attacked by a wolf, which Talbot kills with his silver-headed cane; however, Talbot (who was bitten in the struggle) is found next to the body of Bela.

An old gypsy woman (Maria Ouspenskaya) informs Talbot that Bela was a werewolf and his bite has passed the curse on to Talbot. Now he will transform into a wolf and kill against his will; the only way to end his cursed existence is with silver. The gypsy woman’s prediction comes true, when Talbot changes and kills a gravedigger. He tries to convince his friends and father, Sir John Talbot (Claude Rains), but of course no one believes him. Finally, late at night, he attacks Gwen (Evenlyn Ankers), but Sir John manages to kill him with his silver-headed cane, ending the curse.

ANALYSIS