[EDITOR’S NOTE: Since Tim Burton fans are showing up today in response to our preview of SWEENEY TODD, we thought we would offer up this review of Sweeney’s closest antecedent in Tim Burton’s ouevre.]

[EDITOR’S NOTE: Since Tim Burton fans are showing up today in response to our preview of SWEENEY TODD, we thought we would offer up this review of Sweeney’s closest antecedent in Tim Burton’s ouevre.]

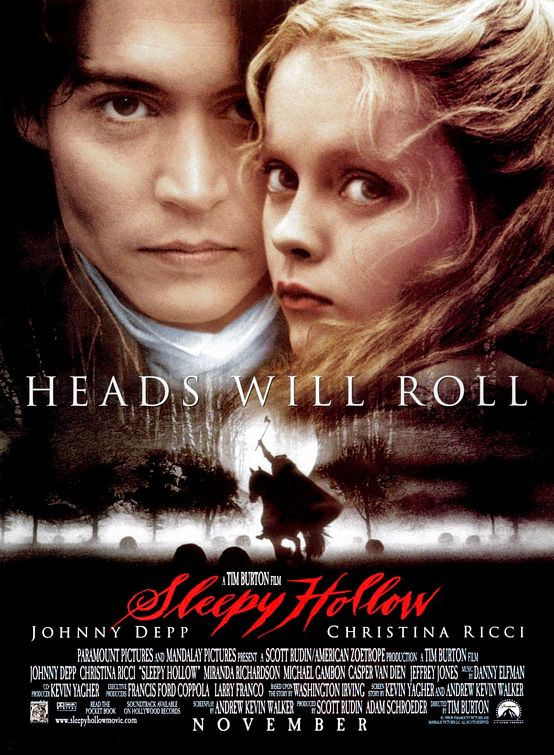

The Headless Horseman rides hell bent for leather in Tim Burton’s elaborate 1999 horror film, derived loosely from Washington Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” There may be some problems in the storytelling and exposition departments, but no one would deny the effective visual scheme that creates a fairy tale world in which the existence of a malevolent Headless Horseman – who returns from the grave to decapitate his victims – is completely believable. Burton’s work is a triumph of style over substance – a visual tour-de-force in which the director’s fairy tale horror aesthetic (so charming in THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS) is rendered in live-action to stupendous effect, overwhelming the weaknesses in the storyline.

One of the great achievement of cinema is the capacity to transport viewers into imaginary worlds – worlds that never existed until the filmmakers created and bequeathed them to us, rendering them as part of our shared conscious experience – a sort of universal dreamscape that we come to recall like lost lands of childhood, half-remembered, somehow unreal, but all the more poignant for their elusive nature. With Tim Burton at the helm of a brilliant production team, SLEEPY HOLLOW achieves this feat to a stunning degree. Burton has coordinated the efforts of the various departments (cinematography, production design, art direction, costuming, make up) into a cohesive whole, formulating a landscape for the town of Sleepy Hollow that both fanciful and convincing. Stitching together threads pulled from his favorite childhood movies, the director has woven a remarkable tapestry. The artificiality of the atmosphere reminds one of Roger Corman’s Poe films (e.g. TALES OF TERROR, MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH, and particularly THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM), which strove to visualize an inner landscape of the mind. The energetic action and colorful outbursts of gory violence, representing the fairy tale battle between Good and Evil, are echo classic ‘60s horror from Hammer Films. And the muted colors of the photograph and production design suggest an attempt to recapture the ambiance of black-and-white Universal horror films from the `30s.

Unfortunately, the script – despite an interesting premise, with a classic monster at its core – cannot sustain the narrative with the grace and economy of the films Burton emulates. The story follows Ichabod Crane (Johnny Depp), an 18th century constable dedicated to replacing superstition with scientific methods in his criminal investigations. Sent to Sleepy Hollow to investigate a series of murders allegedly perpetrated by a Headless Horseman, Crane is a skeptic who insists he will uncover a human murderer, but of course the plot will force him to come to different conclusions. In effect, he starts out as Scully and turns into Mulder halfway through, and the plot comes across like a remake of Jacques Tourneur’s far more sophisticated CURSE OF THE DEMON, in which Dana Andrews` psychiatrist underwent a similar psychological journey.

This character arc worked in CURSE OF THE DEMON because Andrews’ character was a smug scientist who probably deserved a good smack down. It fares less well here because Crane is young and untried, a man of theories but no experience, whose belief in rational thought makes him the clear identification figure for modern movie-goers: when he comes to Sleepy Hollow, you want to see him set these superstitious bumpkins right, but the story is contrived to make him wrong and them right – which muddies the metaphorical waters.

Metaphors aside, the concept wrecks havoc with the plot construction. Crane is a detective, and so the story feels obligated to give him something to detect. The script’s solution is that the Headless Horseman is acting under the control of a living human being who is trying to secure an inheritance by killing off all those who stand in the way, while there is a conspiracy of silence on the issue by several upstanding pillars of the community. This may be good enough for a mystery story, but it is woefully prosaic in the context of a fantasy-horror film.

Rather like STIR OF ECHOES (which also came out in 1999), SLEEPY HOLLOW’s conclusion finds the supernatural elements pushed from center stage, while the mystery story plays itself out in one of those scenes where the villain explains in laborious detail everything that has happened so far. Unlike STIR OF ECHOES, fortunately, SLEEPY HOLLOW redeems itself when the Horseman rides back into the story for a rousing climax, including a genuinely creepy, bloodstained kiss between the dead rider and the mortal who formerly controlled him.

This attempt to impose logic and motivation upon the Horseman’s predations undermines the supernatural ambiance, which is most effective when it is most irrational – that is, when it comes at us like a nightmare that makes sense only in terms of dream-logic. (Think of the horror stories of M.R. James, in which malevolent entities frequently bedevil humans for no good reason at all.) Reducing the Horseman to the instrument of human greed robs him of some of his mythic power. At least in CURSE OF THE DEMON, it was clear that the devil-worshipping Carswell was never fully in control of the demon: he could `cast the runes` in order to target some victim, but once the demon was unleashed, it was beyond the warlock’s power to recall it; in effect, he had little more control than an arsonist who sets a fire but has no way of determining which way the winds will blow. In SLEEPY HOLLOW, on the other hand, the Headless Horseman is ultimately a just a puppet on a chain.

The film is hardly helped by its cynical attitude toward Christianity. In the context of a realistic movie, showing the hypocrisy that underlies a devout exterior, could make for effective storytelling. But in SLEEPY HOLLOW, this approach undermines the classic dichotomy of Good and Evil that infuses the best fairy tales. Blur the lines, and you lose the purity – which is fine if you have something better to replace it, like dramatic complexity (which, sadly, is not on display here). At least viewers can take some solace in the fact that the villain turns out to be that stalwart of childhood tales, the Wicked Stepmother (although her way with an ax, decapitating at least two victims on her own, leaves us wondering why she ever needed to employ the Headless Horseman to do her dirty work).

This revelation of this last plot point almost seems a vestige of earlier drafts, as if it were originally intended to reveal the Horseman as a red herring. Fortunately, the film avoids this cop-out, maintaining a supernatural explanation (unlike the Washington Irving’s story that inspired the script). Even this creates problems, however, as the key scene retained from “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” is fake-out, with romantic rival Brom (Casper Van Dien) dressed up like the Horseman in order to scare Ichabod away from Katrina Van Tassle (Christina Ricci). In the context of the film, the scene is completely gratuitous, never affecting the plot – in fact never even mentioned – even though it should have prompted Crane to point an accusing finger at Brom as the man responsible for using the legend of the horseman to cover up the murders. Quite simply, you could lift the whole sequence out of the film, and it would not be missed; in fact, the narrative would flow smoother without it.

There is a solution that could have tied these plot threads into a satisfying whole: Crane should have been solved the mystery midway, allowing the supernatural element to dominate the third act. Crane should have unmasked Brom as the false horseman, pointed the accusing finger at the conspirators, and triumphantly claimed the mystery to be solved. And only then – just when the story seemed resolved – should the real Horseman have appeared, toppling the tower of logic into a shattered ruin. This would have lent dramatic resonance to scenes that are now just obligatory exposition. It would have wrapped the mundane part of the story early and allowed the glorious imagery to continue unfettered. And it would have given Crane’s character some direction to grow. What is in the story now works as a vehicle for Burton and Depp to play make-believe – very effectively – but the film could have been much more.

Whatever the narrative weaknesses, Burton uses the folktale as license to indulge in amusing theatrics. Because the horror story is both incredible and familiar, the film feels free to jettison verisimilitude, opting for over-the-top gusto instead, in everything from the performances to the music (by Danny Elfman). The familiar clichés are enthusiastically embraced. When Depp intones Crane’s criminological theories, a la Sherlock Holmes, he gives an eye-popping, melodramatic reading that invites us to enjoy the film as a delightful romp. Burton aids in the endeavor with clever camera angles that allow Depp to barge in and out of frame as he makes his points, thus adding far more dramatic emphasis than necessary – and far more than any conventional film could tolerate. Fortunately, in the filmic world of SLEEPY HOLLOW, this exaggerated cinematic style acts as a sort of nudge and a wink to the audience.

Genre veterans Michael Gough and Christopher Lee (who, decades ago, starred together in HORROR OF DRACULA, before going on to appear, separately, in BATMAN and LORD OF THE RINGS) lend strong support in small roles; Martin Landau pops up in a brief, unbilled cameo as an early victim. Christina Ricci is enchanting as Katrina, although the script never quite sells her as a combination of love interest and potential suspect, and the result is that Crane looks a bit of a dullard for not being able to make his mind up about her. Christopher Walken is magnificent in his brief moments as the Hessian Horseman, seen in flashback before losing his head. In a way, he is almost too effective, making it hard for the headless version of the character to measure up, without all those delightful facial grimaces to underline his evil. Only Miranda Richardson falls short. Given the burden of explaining the story, she says her lines very nicely, but she never makes it sound like anything but what it is: obvious exposition. We resent the screen time wasted trying to connect the dots when we want to be terrified by a rampaging force from beyond the grave.

It may seem unfair to enumerate the logical failings of a film that is, at its core, an entertaining spook-show. However, the film has only itself to blame for fusing its fairy tale shudders with an adequate but uninspired mystery plot. This prevents the plot from working in an engrossing way, but if you can sit through the lulls, you will be enthralled when the film gets around to what it does best: scaring the audience with jaw-dropping and completely convincing appearance of a black-robed headless rider charging on his steed through the night, ax in hand, ready for victims. It is an image powerful enough to enshrine the Headless Horseman among the pantheon of classic movie monsters, taking his place not so much beside slasher icons Jason, Freddy and Pinhead as shoulder-to-shoulder with classic characters like Dracula, Frankenstein and the Wolf Man.

Despite the R-rating and numerous beheadings, this is a film that wants to frighten you in in a spooky, friendly way. The violence is meant to shock, but it is hardly disturbing on any profound level. In short, if you enjoy the pleasurable thrill of a good scare, take a trip to Sleepy Hollow.

DVD DETAILS

The DVD presentation of SLEEPY HOLLOW beautifully captures the visual and audio qualities that made the film a blockbuster hit, and adds some extras that help smooth over the weak points, emphasizing the film’s strengths.

The presentation is relatively straightforward, without glitzy animated menus that sometimes seem de rigueur. You get a widescreen presentation that captures the pictorial compositions and maintains the evocative feeling of the cinematography Emmanuel Lubezki and production design by longtime Burton associate Rich Heinrichs, while the Dolby stereo captures the alternating thunder, delicacy and whimsicality of Danny Elfman’s score, along with the menacing sound effects that add emphasize the appearance of the Horseman. The nineteen chapter stops are useful, although fewer than really necessary to pinpoint all the film’s highlights, and the chapter titles don’t always indicate the exact moment when the chapter begins, forcing you to resort to the fast forward button to get to your favorite moments.

The disc includes several extras: two trailers (including a so-called “teaser” trailer that contains much more footage and specific information than usual); cast interviews and information; a behind-the-scenes featurette; a French language option; English subtitles for the hearing impaired; and an audio commentary by Burton.

The featurette is a standard preview-promo piece, shot mostly on location and including snippets with Burton, Depp, Ricci, Walken, Lee, Elfman, and Heinrichs. There are glimpses of Burton’s preliminary sketches, intercut with corresponding shots from the film. Some special effects techniques are revealed, such as the mechanical horse used for shots of Walken riding, not to mention the blue mask that allowed ILM to remove the Horseman’s head from the scene (the horseman’s collar, which would have been obscured by the blue-encased head of the stunt man, had to be added digitally). Curiously, there are numerous shots of Lisa Marie as Lady Crane, but no mention of her name.

The cast interviews contain material taped after the film’s completion, at a press junket. Some information from the featurette is recycled, but there are also some spoilers that should not be viewed until you’ve seen the film. In one strange moment, Depp claims he obtained the restraining-torture device seen behind him in the courtroom scene near the film’s beginning; no explanation is given as to why he wanted it or to what use he puts it.

The audio commentary by Burton turns out to be amusing and jovial, providing much enthusiasm and humor, while also giving us an insight into what makes him tick as an artist. At the same time, Burton would have benefited from having an interviewer who could steer him to certain topics or at least make him reveal a few more details. For example, the director mentions that the opening scenes gave him a chance to work with cinematographer Conrad Hall, but he never mentions why Hall shot these scenes instead of Lubezki, who handled the rest of the filming. Later, Burton mentions that the flashback torture and death of Lady Crane was inspired by Mario Bava’s Black Sunday and Roger Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum, but he neglects to mention the common link between those two films: star Barbara Steele. And details regarding the script and Burton’s creative relationship with screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker (if any) are almost non-existent.

Fortunately, Burton compensates for these lapse by providing numerous interesting tidbits. He mentions that Hall and Martin Landau (glimpsed in an unbilled cameo as a victim) had worked together on the Outer Limits episode “The Man Who Was Never Born.” He reveals that playwright Tom Stoppard (Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead) contributed to the script’s dialogue, enhancing its humor. And he marvels over cinematographer Lubezki’s ability to create an illusion of depth on interior stages portraying exterior locations, mostly through the use of copious amounts of fog to hide the rafters and lights.

Even better are Burton’s amusing comments. He marvels over Jeffrey Jones’ wig (“an image that stays with you, whether you want it to or not”). When Depp brandishes a pistol, Burton calls the scene “18th Century Starsky and Hutch.” During exposition scenes, he admits the film feels like an episode of “Scooby Doo, Where Are You,” and he wonders whether the whole costume-period setting isn’t just reminiscent of a bad “Merchant Ivory movie.” Best of all, he jokes that during the fight scenes he felt as if shooting an expensive Mexican wrestling movie, because the stunt man’s blue mask (used on set to make it easer to remove his head with computer effects in post-production) made the Headless Horseman resemble Blue Demon (a Mexican wrestler and movie star from the ‘60s).

Fans of SLEEPY HOLLOW and of Tim Burton will be pleased with this DVD, and older fans of classic Hammer Horror will be happy to hear Burton acknowledge this influence on the film. The director clearly wanted to make a film in that tradition of the monster movies he enjoyed as a child, and he managed to accomplish this task without simply producing a carbon copy. The result may not be a masterpiece (how many of our favorite horror movies are?), but its strengths may be enough to earn it a reputation as a classic.

SLEEPY HOLLOW (1999). Directed by Tim Burton. Screenplay by Andrew Kevin Walker from a screen story by Walker and Kevin Yagher, inspired by Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” Cast: Johnny Depp, Christina Ricci, Miranda Richardson, Michael Gambon, Casper Van Dien, Jeffrey Jones, Richard Griffiths, Ian McDiarmid, Michael Gough, Christopher Walken, Marc Pickering, Lisa Marie, Steven Waddington, Claire Skinner, Christopher Lee, Alun Armstrong, Martin Landau.

3 Replies to “Sleepy Hollow (1999) – Film & DVD Review”