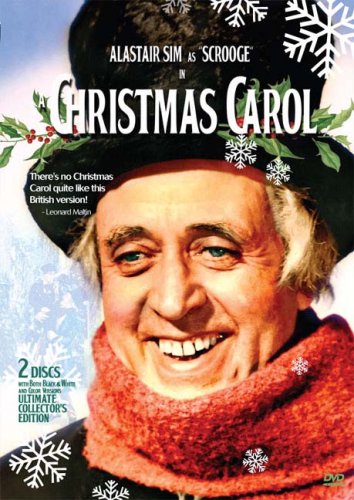

For many decades, this 1951 production was considered to be the best adaptation of Charles Dickens’ A CHRISTMAS CAROL, and it is easy to see why: it features excellent production values and a wonderful performance by Alastair Sim as Scrooge. Ironically, it is also one of the less faithful adaptations, featuring considerable revisions and additions by screenwriter Noel Langley; fortunately, these changes give SCROOGE a life of its own, allowing it to stand as a great film, not merely a good adaptation of great source material. Although several subsequent adaptations have come along to challenge SCROOGE’s supremacy, none of have eclipsed it.

Departures from the original text begin almost immediately, with the film opening at the business exchange instead of within Scrooge’s office; outside, a debtor asks for more time to repay a loan, and Scrooge encounters the two men seeking charity for the poor. Sims gives us an immediate glimpse into his interpretation of the hard-hearted old sinner: a bemused Scrooge whose attitude seems to irritate more than dismay the charity-seekers.

We also see that the dialogue is considerably condensed from the book. Purists may object, but the screenplay retains the essence and allows the film to move at its own pace, with room for additional scenes such as Tiny Tim staring wistfully into a toy shop window (as sometimes happens in films, he does not look deathly ill, but his brightness is waning), followed by a scene of old Ebenezer Scrooge dining on his way home from work (a scene also in the 1935 film, starring Seymour Hicks). In an amusing throw-away bit, Scrooge asks the waiter for more bread, then changes his mind when he learns he will be charged extra for it.

The presentation of the ghosts is effective, beginning with Scrooge’s late partner Jacob Marley, who in this version is heard before he is seen, his voice calling out to Scrooge before his face appears on the front door’s knocker. Adding a new twist to the old bit, after Scrooge gets inside and sits down to his gruel, the bells begin ringing by an unseen hand – but this time, they do not actually movie; only the sound is heard, distorted on the soundtrack to suggest the supernatural.

Sims does a good job registering dread before Marley appears; he even screens when his bedroom doors bang open, allowing the ghost to enter. Atypically, Michael Hordern plays Jacob without th bandage around his head (there to keep the deceased’s jaw from dropping open – which is exactly what happens when Marley takes it off in the book). Hodern’s is a tormented Marley, rather than the baleful Leo G. Carroll interpretation of A CHRISTMAS CAROL (1938). His shrill scream is as much from his own agony as from trying to convince Scrooge that he is indeed seeing a ghost, not a hallucination brought on by a bit of “underdone potato.” (This line is often omitted from film adaptations. In a script notable for condensing the text, it is interesting to see this often neglected bit of dialogue retained.)

Another often discarded bit is retained when Marley directs Scrooge to gaze out the window, whereupon he sees other helpless, hopeless souls in Marley’s predicatment – wandering, unseen phantoms, unable to alleviate human suffering.

The Ghost of Christmas Past is here portrayed as an old man (Michael Dolan) in vaguely Grecian robes – a change the angelic outline of th 1935 version and the woman of the 1938 version. (The vaguely androgynous approach to the character would be incorporated into subsequent versions.) When the spirit takes Scrooge back to his old school to see his younger self visited by his sister Fan, the young girl runs through him, unaware of his presence.

The script presents Scrooge as the younger sibling, whose birth killed his mother (accounting for his father’s cold indifference to Scrooge). This is also used to increase our understanding of why Scrooge dislikes his nephew: Fan died giving birth to him, just as Ebenezer’s mother died giving birth to him.

The scenes of Christmas Past are the most augmented in the screenplay, which is less interested in tracking Ebenezer Scrooge’s loss of love than in depicting his rise as a business man. When young Scrooge’s employer, Fezziwig, turns down a chance to sell off his business, young Scrooge takes a job with the rival company. Fan’s deathbed scene is depicted, with the old Scrooge registering convincing anguish at his past behavior. We then see the young Scrooge meeting a young Jacob Marley at his new job. This company apparently drives Fezziwig out of business and seizes its assets, allowing young Scrooge to take on the now unemployed Bob Cratchit as his clerk – at a reduced salary, of course.

Later, the company employing young Scrooge and Marley runs into trouble when its boss is caught embezzling funds. The two young men offer the board of directors: they will help them avoid a scandal by making up the losses to investors, but in exchange, they get a controlling interest in the company.

Years later, Marley lies on his deathbed on Christmas eve (a scene mentioned but never visualized before) while Scrooge refuses to visit him until after business hours. Marley offers a deathbed warning – as if, hovering on the point of death, he has had a premonition of what awaits on the other side of the grave.

After this much expanded sequence, the rest of SCROOGE sticks a bit closer to the basic outline of A CHRISTMAS CAROL, but there are still interesting additions. Now accompanied by the Spirit of Christmas Present (a lively Francis DeWolfe), Scrooge sees his former fiancee working to help the poor (usually, Scrooge sees a glimpse of her with a happy family, illustrating the life Ebenezer could have had, but lost). In this version version the Spirit of Christmas Present does offer a grim glimpse of mankind’s horrible children, Ignorance and Want, who are also occasionally omitted from other films.

One of the most memorable images in an filmization of A CHRISTMAS CAROL is the presentation of the ominous Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Here the spirit is presented mostly as an immobile silhouette, a figure enclosed in an impenetrable pitch-black shroud that suggests a monk more than the Grim Reaper (as he is so often depicted); his hand, the only part of his body glimpsed, is pale white rather than skeletal. Although not as outright horrific as some other versions, the Spirit of Christmas Future retains his power to intimidate, and we feel for Scrooge when in spite of his sincere wishes, he expresses doubts about his ability to change at his old age.

One of the most memorable images in an filmization of A CHRISTMAS CAROL is the presentation of the ominous Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. Here the spirit is presented mostly as an immobile silhouette, a figure enclosed in an impenetrable pitch-black shroud that suggests a monk more than the Grim Reaper (as he is so often depicted); his hand, the only part of his body glimpsed, is pale white rather than skeletal. Although not as outright horrific as some other versions, the Spirit of Christmas Future retains his power to intimidate, and we feel for Scrooge when in spite of his sincere wishes, he expresses doubts about his ability to change at his old age.

There is an extremly poignant scene of Bob Cratchit lamenting the death of Tiny Tim – a good example of the film taking a potentially maudlin moment, whose emotional value could have been sucked dry through familiarity, and completely recharging it so that it feels fresh and new again.

This invigorating sense of the new continues when Scrooge awakens after his glimpse of the future. Sims’ giddy delight – the sense of a burden lifted and a new life begun – is a joy to behold, and the script builds it up by adding a scene of Scrooge encountering his charwoman (the very same one who in Scrooge’s vision of Christmas Future was seen selling his bedclothes after his death). Her hysterical reaction to Scrooge’s overnight metamorphosis underlines the extraordinary event, providing a moment for Sims to flash a small sign of regret over the lost years while insisting to the woman that he has not taken leave of his senses. (This new scene incorporates some dialogue that usually takes place between Scrooge and the young lad whom he sends to purchase a goose for the Cratchit family dinner – another example of SCROOGE tinkering with the original text to create something new that works for the film as a film, rather than as a faithful adaptation.)

Scrooge’s awakening feels like a breath of relief, thanks in large part to Sims, who is the first on-screen actor to give old Ebenezer some semblance of reality. His Scrooge is more than a one-dimensional caricature of a greedy old man; Sims gives the character some glimpse of an inner life, the ghost of what he once was, which is fully glimpsed again when he is reborn on Christmas Day. At the same time, the miraculous transformation has not completely oblitered memories of his wasted years, which flicker briefly across his eyes while telling his charwoman that he is not bad; fortunately, in the end, the spirit of Christmas is overcomes even these regrets: Scrooge admits to himself that he does not deserve to be so happy, and yet he is happy, regardless.

That image of a soul once dead, now renewed, is projected through Sims’ face without undue melodrama or overdone mugging. In the middle of a fine film that works on all technical levels, it is this performance that gives SCROOGE the life it needs to live on as a classic that stands the test of time, worthy of its high reputation.

SCROOGE (1951). Directed by Brian Desmond Hurst. Screenplay by Noel Langley, based upon “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. Cast: Alastair Sim, Kathleen Harrison, Mervyn Johns, Hermione Baddeley, Michael Hordern, George Cole, John Charlesworth, Francis De Wolff, Rona Anderson, Carol Marsh, Brian Worth, Miles Malleson, Ernest Thesiger.

[serialposts]