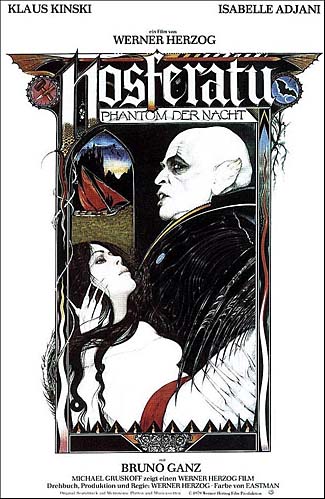

Werner Herzog’s remake of the 1922 silent film (directed by F. W. Murnau) has sometimes been dismissed for being too slowly paced and too slavish to its source, but in fact it is superior to the original film. Although occasionally marred by Herzog’s heavy-handed, trademark stylistic tics, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE stands on its own as an interesting addition to the filmmaker’s oeuvres.

Werner Herzog’s remake of the 1922 silent film (directed by F. W. Murnau) has sometimes been dismissed for being too slowly paced and too slavish to its source, but in fact it is superior to the original film. Although occasionally marred by Herzog’s heavy-handed, trademark stylistic tics, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE stands on its own as an interesting addition to the filmmaker’s oeuvres.

The story line parallels that of Murnau’s film while reinserting material from Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula – most obviously the character names (which were changed in the original in a failed dodge to avoid copyright infringement claims). The movie begins with an extended prologue of Jonathan Harker (Ganz) taking leave of his wife Lucy (Adjani) at the orders of his employer Renfield (Topor). Harker travels to Transylvania to complete the sale of a property to Count Dracula (Kinski), who turns out to be a vampire. After biting Harker, the Count proceeds to Germany, bring rats and a deathly plague with him. Harker eventually finds his way home, but he has lost his memory of Lucy. Lucy deduces the truth about Dracula and sets about destroying his hiding places by placing sacred communion wafer in his coffins. Finally, she destroys the vampire by luring him to her side during the night; seduced by her charm, Dracula remains at her side, sucking her blood, until morning, when the sunlight destroys him. Professor Van Helsing (Ladengast) shows up and puts the icing on the cake by driving a stake through the Count’s heart, after which he is arrested by the police for murder. Lucy expires from loss of blood, but Harker revives from his lethargy, mumbles something about having “much to do,” and rides off into the sunrise, apparently taking on the mantle of the vampire.

Herzog’s film frequently flirts with the ridiculous. When Harker tries to escape Castle Dracula, there is an anonymous peasant playing a violin in the courtyard: who he is and what he is doing there is never given so much as lip-service explanation; his unexplained appearance feels like a parody of bad art house filmmaking. Van Helsing’s arrival to finish off the vampire – who is clearly already dead from exposure to sunlight – feels a day late and a dollar short. Worse, after staking the Count (off-screen) he appears with the bloody stake in his hand, implying he drove it through the Count’s chest and withdrew it immediately afterwards; this was clearly a lazy way of putting the incriminating evidence in his hands, to justify his arrest by the police. Harker, instead of being cured by the death of Dracula, transforms into a vampire himself and immediately rides into the sunrise – the very same sun that just killed the Count!

In spite of these missteps, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE maintains a curiously hypnotic hold on the audience. Herzog’s camera captures impressive location footage of craggy mountains, cloudy skies, and cascading waterfalls for Harker’s trip to Transylvania, suggesting awesome and mysterious forces of nature as the young man leaves civilization behind and heads into the unknown (a facet of the novel seldom fully realized on screen). The cool colors of the photography seem drained of blood, drained of life, suggesting the Count’s eternal, lonely existence. Kinski delivers a strangely moving performance, both threatening and sad; he truly conveys a sense of an immortal monster moving agelessly through the ages of a dull existence, grasping for life that will revive him.

Adjani is perhaps the Count’s most memorable on-screen “victim” – she, not Van Helsing or Harker, is the true hero of the film. Unlike her equivalent in the silent version, Lucy does not simply sacrifice herself; she tracks down the vampire and destroys his lairs with the Eucharist, restoring the novel’s clash of the Sacred and the Satanic. This element was completely missing from Murnau’s version, which traded in a simpler anti-Semitic metaphor that cast the vampire as a Jewish sterotype who was destroyed by the sacrifice of a pure Rhine maiden.

Adjani is perhaps the Count’s most memorable on-screen “victim” – she, not Van Helsing or Harker, is the true hero of the film. Unlike her equivalent in the silent version, Lucy does not simply sacrifice herself; she tracks down the vampire and destroys his lairs with the Eucharist, restoring the novel’s clash of the Sacred and the Satanic. This element was completely missing from Murnau’s version, which traded in a simpler anti-Semitic metaphor that cast the vampire as a Jewish sterotype who was destroyed by the sacrifice of a pure Rhine maiden.

In the end, NOSFERATU THE VAMPYRE is far from completely satisfying as a horror film or as an adaptation of Stoker’s Dracula. Its strengths are as an auteur piece, with Herzog once again working his magic, as he takes on a subject that showcases a clash between the civilized and the wild. Harker’s trip takes him from civilization into the heart of darkness, where dreams become reality. The Transylvanian populace resembles the superstitious natives of AGUIRRE, THE WRATH OF GOD. Kinski’s Dracula is another obsessed, driven character, like the ones he played for Herzog in AGUIRRE and FITZCARALDO.

The narrative lapses are indicative of thematic ambitions: whereas the original NOSFERATU was an allegory for the rebirth of Germany after the First World War, the remake’s more cynical ending suggests the horrors yet to come in World War II. Though it may not be what the average horror fan is seeking, NOSFERATU survives its flaws to emerge as a haunting, memorable film that eschews crude shocks in the quest to achieve something finer – a dreamlike disquiet meant to disturb the soul.

PRICELESS MOMENT

Count Dracula and Renfield share only one moment on screen together, in which the vampire-slave relationship plays out like a rock star dismissing a fawning fan. As the Count stands quietly in the twilight, the groveling madman tugs at his coat, begging to be of assistance. A clearly annoyed Dracula shrugs him off and tells him to travel to another city, and the plague will travel with him. As a thankful Renfield capers off, the Count rolls his eyes as if to say, “I thought he’d never leave.”

TRIVIA

NOSFERAU THE VAMPYRE was part of a vampire renaissance in the 1970s that saw no less than three Dracula films released in 1979. The other two were the remake of DRACULA starring Frank Langella and LOVE AT FIRST BITE, starring George Hamilton.