[EDITOR’S NOTE: As part of our on-going celebration of Mario Bava this week, we enlisted the aid of Keith Brown, who writes voluminously – and, more important, fascinatingly – on the subject of Italian cinema.]

An Appreciation by Keith Brown of Giallo Fever

If there’s one word which encapsulates the world of Mario Bava’s cinema for me it would probably be irony. Here was someone who virtually had to be pushed into the director’s chair to make his official debut at the age of 45, but thereafter seemed unable to say “no” to just about any project that came his way, racking up 20 or so directorial credits in not quite as many years. Here was someone who went from the poverty-row circumstances of PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965) and KILL BABY KILL (1966) to the major league with Dino de Laurentiis on DIABOLIK (1968), only to find that he wasn’t comfortable actually having money and time available. Here was someone who was given a clean bill of health by his doctor days before his fatal heart attack in April 1980. Here was someone who contrived to die the same week as Hitchcock so that his passing went almost unnoticed, yet he has since been heralded by the likes of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Tim Burton. And, above all, here is someone whose films continually show up the distance between appearances and reality to delight, surprise and shock you: the apparent junkie in BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964) who turns out to be an innocent diabetic; the sinister seeming witch in KILL BABAY KILL whose ministrations are in fact purely beneficient (and whose malign counterpart is the virtual definition of innocence); or, above all, the countless figures whose conceal the basest of desires behind a facade.

If there’s one word which encapsulates the world of Mario Bava’s cinema for me it would probably be irony. Here was someone who virtually had to be pushed into the director’s chair to make his official debut at the age of 45, but thereafter seemed unable to say “no” to just about any project that came his way, racking up 20 or so directorial credits in not quite as many years. Here was someone who went from the poverty-row circumstances of PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965) and KILL BABY KILL (1966) to the major league with Dino de Laurentiis on DIABOLIK (1968), only to find that he wasn’t comfortable actually having money and time available. Here was someone who was given a clean bill of health by his doctor days before his fatal heart attack in April 1980. Here was someone who contrived to die the same week as Hitchcock so that his passing went almost unnoticed, yet he has since been heralded by the likes of Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino and Tim Burton. And, above all, here is someone whose films continually show up the distance between appearances and reality to delight, surprise and shock you: the apparent junkie in BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964) who turns out to be an innocent diabetic; the sinister seeming witch in KILL BABAY KILL whose ministrations are in fact purely beneficient (and whose malign counterpart is the virtual definition of innocence); or, above all, the countless figures whose conceal the basest of desires behind a facade.

Bava worked as a cinematographer and general cinematic jack-of-all-trades prior to making his directorial debut. The two most important films of this period are Freda’s I VAMPIRI (1956) and CALTIKI THE IMMORTAL MONSTER (1959) as on each occasion Bava was charged with completing the film after director Ricardo Freda abandoned ship.

Production circumstances and genre aside, I VAMPIRI and CALTIKI are different: In hindsight I Vampiri emerges as the home-grown founding text for the next quarter century of Italian horror production, freely mixing mad science; gothic and detective thriller motifs. CALTIKI by contrast presents its makers’ engagment with foreign traditions, borrowing liberally from THE BLOB and the Hammer ‘X’ films THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT and X THE UNKNOWN but giving them a distinctively Italian-style makeover in a way that was to also become familiar over the coming years, most obviously with the spaghetti westerns of the 1960s.

It has sometimes been suggested that Bava would never make another film as good as his debut, BLACK SUNDAY (1960). Whether or not you agree with this statement – personally I don’t – it is a fitting testament to the sheer impact of the film itself, whose post-Hammer shocks, beginning with the hammering of a spiked mask onto the witch Asa’s face, were sufficient for it to be denied a release in the UK for close on ten years. BLACK SUNDAY’s other key claim to fame is, of course, that of inaugurating the career of Barbara Steele, the fetish star of 1960s Italian horror, who plays what was to be the first of many dualistic-cum-schizophrenic sado-masochistic roles as the re-incarnated witch and her innocent target Katia.

Had Bava done nothing other than realise Steele’s potential his place in the history books would have been assured. As it was, however, he did much more, following the hallucinatory horror-peplum HERCULES IN THE HAUNTED WORLD (1961), starring Christopher Lee as the Dracula-esque Lyco, with the first giallo to really be worthy of the name, THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1963).The first of Bava’s Hitchcockian films, THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH is also one of his most ironic, self-reflexively exploring issues of fiction and reality as a habitual reader of murder mysteries finds herself plunged into a not dissimilar scenario shortly after arriving in Rome for a holiday and proceeds to misread just about every clue placed before her while somehow muddling through to a happy ending.

There were to be no happy endings in the anthology film BLACK SABBATH. Released in the same year as THE GIRL WHO KNEW TOO MUCH and THE WHIP AND THE BODY in what was something of an annus mirabilis for Bava, the film makes yet another significant contribution to the formation of modern horror as the first in which evil wins. Yet it also does so in a way that is different from the later likes of NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD, presenting itself as artificial rather than real. As Boris Karloff, the monster and master of ceremonies, remind us in the coda, there are really no such things as vampires; it’s “only a movie, only a movie…”

Though Steele would have been ideal for the role of Nevenka Menliff in THE WHIP AND THE BODY opposite Lee’s prodigal son who everyone else wishes would just go away, Daliah Lavi proves about as good a substitute as could be imagined. One of Bava’s most challenging films, dealing with themes of sadomasochism and amour fou in a serious and mature manner, critical reaction to the film was muted on account of the drastically recut matinee audience friendly versions which circulated internationally. Never has a retitling – WHAT – been more apt.

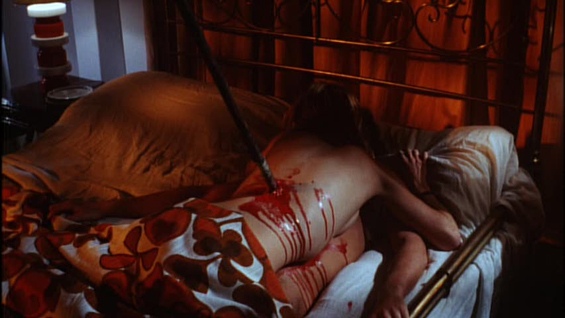

It’s impossible to say anything new about BLOOD AND BLACK LACE (1964): It’s the giallo by which all others are measured and which, for better or worse, inaugurated the body count film. It’s also a stunningly brutal and beautiful work that few if any of its innumerable imitators have been able to match on either counts, let alone surpass on one or both or in terms of overall cinematic intelligence and aptitude.

Unfortunately for Bava audiences in Italy and elsewhere were not quite ready for the giallo at this time, prompting a move into the spaghetti western with THE ROAD TO FORT ALAMO (1964), generally regarded as one of his lesser and less successful films; much the same can be said of Bava’s other ventures into the filone, RINGO FROM NEBRASKA (1966) and ROY COLT AND WINCHESTER JACK (1970).

That Bava found science-fiction more to his liking is evident from PLANET OF THE VAMPIRES (1965). Outdoing ALIEN on a budget that stretched to little more than a couple of papier mache rocks and some dry ice for the alien planet and space Nazi costumes for the crews of the crashed spaceships, the film also features a delicious, characteristically oh-so-Bava sting in the tale…

The following year saw no fewer than four films from Bava: the aforementioned Ringo from Nebraska; the ill-advised Vincent Price vehicle DR GOLDFOOT AND THE GIRL BOMBS; the spaghetti-esque historical adventure KNIVES OF THE AVENGER, which saw Bava reuinted with BLOOD AND BLACK LACE leading man Cameron Mitchell, and KILL BABY KILL. Though its title may be stupid, the film is anything but, cleverly blending giallo and Gothic motifs as the rational scientific investigative hero is forced to realise that the reality of the supernatural, epitomised by the oft-quoted scene in which he pursues a ghostly child and himself through the castle chambers.

The commercial high point of Bava’s career was the aforementioned DIABOLIK. Though hampered by De Laurentiis’s absurd desire to tame the Giussani sisters’ character for the censor and the box-office Bava’s evident understanding of the fumetti aesthetic shines through, resulting in a pop-art masterpiece that’s been identified as the most faithful comics book adaptation by artist and cult film scholar Steve Bissette and referenced by the likes of Burton’s BATMAN and Roman Coppola’s CQ.

Following DIABOLIK Bava made three intriguing gialli in as many years, the Hitchcockian A HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON (1969) and the BLOOD AND BLACK LACE deconstructions FIVE DOLLS FOR AN AUGUST MOON and A BAY OF BLOOD (1971). Benfitting or suffering from a surfeit of modish designs (look up kitsch or camp in the dictionary and you can almost imagine any frame from Five Dolls appearing as an illustration) and stylistic tropes, they’re films which play with the thriller form and the audience’s expectations. Thus in A HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON our protagonist immediately informs us that he’s a schizophrenic killer, who murders newlyweds and brides to be because with each fresh crime he recalls a bit more of a traumatic incident from his past. Yet the resolution to this trauma is obvious to any viewer who knows their Freud. Similarly in A BAY OF BLOOD we’re given so many suspects, murderers and victims that it soon becomes impossible, if not irrelevant, whodunit. Just about everyone does it or has it done to them, until there were none – and all for a bay whose poisonous nature is foregrounded by a credits sequence into which a fly (a recurring creature in Bava’s work, also showing up in an episode of BLACK SABBATH and HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON) suddenly drops dead.

1972 was a pivotal year for Bava, not so much for the two films he made – the underrated FOUR TIMES THAT NIGHT, which reworks Rashomon as a sex comedy and was almost blocked from release by his former mentor Freda, and the old fashioned if effective gothic romp Baron Blood – as for inaugurating his relationship with Italian-American independent producer Alfredo Leone.

Having produced BARON BLOOD, Leone gave Bava virtual carte blanche on his next film, LISA AND THE DEVIL (1973). It was to be a dream project that quickly turned into a nightmare as Leone held off selling the rights to the film in the hope of better offers, only for prospective buyers to then see the film and realise that its poetic art-horror approach was not what they were after for the grindhouse and drive-in crowds anyway. Seeking to recover his losses, Leone had Bava reluctantly retool the film into the cod-EXORCIST shocker HOUSE OF EXORCISM, the less about which said the better. (Saying that you prefer HOUSE OF EXORCISM to LISA AND THE DEVIL is probably the ultimate heresy as far as the Bava fan is concerned, so if you’re feeling brave at one of the retrospective screenings…)

Bava’s next project was even more ill-fated. KIDNAPPED a.k.a. RABID DOGS a.k.a. SEMAFORO ROSSO (1974/1998) is the film that should have re-established his place at the forefront of the Italian popular cinema, showing that he could do hard-hitting, realistic crime actioners with the best of them whilst still accomodating that distinctive ironic touch. Unfortunately his backers ran out of money and the uncompleted film was impounded, not to be released for over 20 years. The film has been described as RESERVOIR DOGS meets LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT in a moving car. It’s not a bad description and indeed almost undersells it: rough around the edges though the reconstructions may be, KIDNAPPED is that good.

SHOCK followed in 1977. Bava’s last film as a director, it saw his son and long-time assistant Lamberto taking an increasing role and thus presents an intriguing baton-passing from father to son, as a kind of transition point from such forerunners as THE WHIP AND THE BODY, KILL BABY KILL and LISA AND THE DEVIL to its successor MACABRE (1980). Bava’s last work as a cinema magician was providing special effects for Dario Argento’s INFERNO (1980), on which Lamberto served as assistant director. The elder statesman of Italian macabre cinema helped his younger successor make the Italian-produced movie look as though it was set in New York, and he conjured up a wonderful scene of one of the Three Mothers of Darkness materializing out of a mirror. Appropriately, the staging of the shot recalled a similar set-up in BLACK SUNDAY, bringing the Bava horror legacy full circle.

RELATED ARTICLES:

3 Replies to “Mario Bava: Master of Illusion”