All too predictably, this remake of the Hong Kong horror film THE EYE (“Gin Gwai,” 200) recreates the original story with slick but anonymous Hollywood production values replacing personal vision. By now, the formula has become so mechanical that one wonders whether the filmmakers could be replaced with some kind of device, the cinematic equivalent of Photoshop, which would take the existing work and “retouch” it according to a programmed set of parameters: The dialogue must be translated into English. The location must be shift to the United States. The story should be presented more or less intact even if it makes less sense in its new language and location. To compensate for anything lost in translation, a few extra jump-scares should be added at arbitrary moments. The horror scenes should be enhanced with more elaborate makeup and/or special effects. The cast should be young and beautiful but not necessarily talented or famous. The script should spell everything out in letters as big as those on top of an eye-exam chart, lest viewers be too short-sighted to spot subtle details; and just in case, the actors should read the chart loudly, slowly, and clearly, so that the audience will hear everything they failed to see on their own. In the case of THE EYE, the result feels like a case of the blind leading the (presumed) blind – the filmmakers keep point to details that we see coming from a mile away.

All too predictably, this remake of the Hong Kong horror film THE EYE (“Gin Gwai,” 200) recreates the original story with slick but anonymous Hollywood production values replacing personal vision. By now, the formula has become so mechanical that one wonders whether the filmmakers could be replaced with some kind of device, the cinematic equivalent of Photoshop, which would take the existing work and “retouch” it according to a programmed set of parameters: The dialogue must be translated into English. The location must be shift to the United States. The story should be presented more or less intact even if it makes less sense in its new language and location. To compensate for anything lost in translation, a few extra jump-scares should be added at arbitrary moments. The horror scenes should be enhanced with more elaborate makeup and/or special effects. The cast should be young and beautiful but not necessarily talented or famous. The script should spell everything out in letters as big as those on top of an eye-exam chart, lest viewers be too short-sighted to spot subtle details; and just in case, the actors should read the chart loudly, slowly, and clearly, so that the audience will hear everything they failed to see on their own. In the case of THE EYE, the result feels like a case of the blind leading the (presumed) blind – the filmmakers keep point to details that we see coming from a mile away.

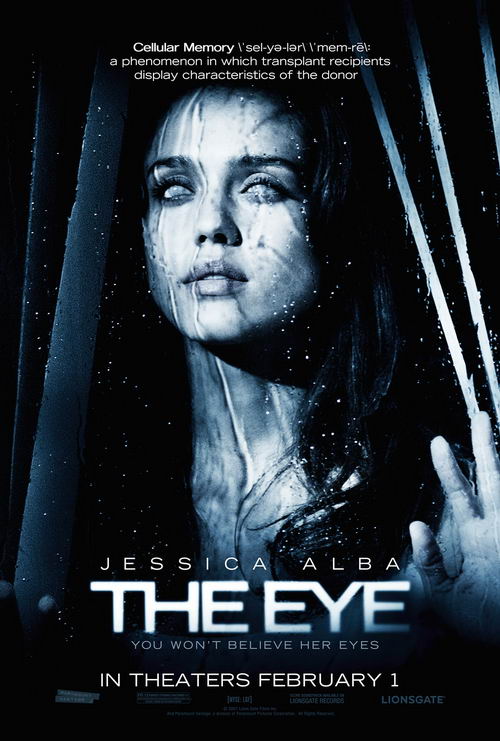

The story features Jessica Alba as Sydney, a blind violinist who is able to see again after a corneal implant. Unaccustomed to vision, she cannot account for some of the strange sights she sees, including frightening figures who arrive to collect the souls of the dead at her hospital. Later, a series of visions and nightmares (including a rather lame haunted oven – shades of GHOSTBUSTERS’ haunted refrigerator) leads Sydney to discover the identity of her donor. This turns out to have been a young woman in Mexico, branded as a witch because she could forsee impending death (which she was powerless to prevent, because her warnings went unheeded). On the way back from Mexico, the violinist and her doctor are trapped in a traffic jam: visions of flaming explosions foretell of approaching disaster, but can it be prevented…?

Ripped from its cultural context, the story seems contrived and artificial, a curious spooky tale worth being retold at a slumber party sleepover but lacking much conviction. For example, in the original, the dark and placid figures who escort souls to the afterlife are based on the Buddhist equivalent of the Angel of Death; here, they are rendered as generic scarey boogeymen, who snarl a lot because they do not appreciate being observed by the living. Without the underlying belief system to buttress the story, the film wobbles with uncertainty. Sydney objects that her doctor does not believe her visions, but it is not clear what she believes them to be; she merely says that what she is seeing is “impossible,” imlying a certain lack of belief on her own part.

This uncertainty weakens the character, a problem exacerbated by the film’s attempt to play up her emotional distress. In a silly piece of melodrama that stalls the story midway, Sydney decides she has had enough of visions, breaks all her lighting fixtures, and wraps a cloth over her eyes, recreating her former blindness. In the context of a genre piece, the film simply is unable to sell the “drama,” which seems forced and contrived. (Curiously, Sydney’s whining self pity more closely resembles the ill-conceived characterization from THE EYE 2, which also short-circuited the story.)

Although Alba tries hard, she fails to overcome this limitation in the writing. She ably conveys Sydney’s emotional reaction to regaining her sight, but the script expects the impossible: Sydney is supposed to be simultaneously freaked out by her condition and also strong and determined enough to overcome it. This leads to some bizarre moments, such as an early scene wherein Sydney attempts to convince her doctor of her sincerity by taking his face in both hands – a ridiculously intimate gesture at far too early a stage in their relationship. (As dubious as the gesture is, far more amusing is the reaction – or non-reaction – of her doctor, played by Alessandro Nivola, to being touched by his ravishingly beautiful patient: no conflicting waves of attraction and guilt, of romantic desire checked by professional ethics. At most, he looks vaguely uncomfortable, like a teen-aged boy receving an unwanted kiss from his Great Aunt Tilly.)

To be fair, if you have not seen the original, the new version of THE EYE works well enough as a technically competent but artistically uninspired scare show; it faithfully recreates the original scares (including the famous elevator scene) and adds one or two new jumps. There are even one or two instances where, rightly, the filmmakers attempt to correct flaws in the original vision.

We see a bit more of Sydney adjusting to life with vision. One very nice shot displays her adjusting to walking down crowded sidewalks, bumping into pedestrians who expect her to do her share in avoiding collisions – something she never had to worry about when her white can tipped people off to her blindness. There are other nice details: watching Sydney learn to sight read musical notation or falling back on her old habit of using an index finger to judge when a glass is full.

The screenplay also attempts to improve upon the ending. As good as the original EYE was, its story did feel a bit arbitrary; its full-circle structure left you feeling as if you had gone on a journey only to return to the same place, wondering what was the point. The remake goes for a SIGNS-type approach, implying that all the suffering and confusion was a thorny path leading to a decisive moment when Sydney can come to the rescue. It’s a laudable attempt to re-think something that did not quite work the first time, but it comes across as too pat. The closing narration, which spells it all out, only aggravates the problem.

As expected THE EYE ends up looking like a glassy imitation of its progenitor. It’s a bit dull and colorless; adding a nifty set of contacts or a stylish pair of shades is not enough to hide the deficiency. At least the film is not much worse than THE EYE 2, and it is considerably less ridiculous than the misguided THE EYE 10. The next time someone returns to this franchise, instead of a little cosmetic surgery, they should try a complete transplant.

TRIVIA

Patrick Lussier is listed in the credits as “Visual Consultant,” a job description that is not defined by any guild; Lussier previously had this credit on DARKNESS FALLS and WHISPER. Lussier’s more traditional credits include editing several films for Wes Craven (including SCREAM) and directing several direct-to-video films (including DRACULA 2000 and WHITE NOISE 2).

THE EYE (2008). Directed by David Moreau & Xavier Palud. Screenplay by Sebastian Gutierrez, based upon the the screenplay for GIN GWAI by Jo Jo Yuet-chun Hui, Oxide Pang & Danny Pang. Cast: Jessica Alba, Alessandro Nivola, Parker Posey, Rade Serbedzija, Fernanda Romero, Rachel Ticotin, Obbat Babatunde, Danny Mora, Chloe Moretz, Brett Haworth, Kevin K. Tamlyn Tomita.

FILM REVIEWS: The Eye – The Eye 2 – The Eye 10

ARTICLES: Remaking Asian Horror – A Brief History

17 Replies to “The Eye (2008) – Horror Film Review”