Mater Lachrymarum, Our Mother of Tears. She it is that night and day raves and moans, calling for vanished faces. She stood in Rama, when a voice was heard of lamentation – Rachel weeping for her children, and refusing to be comforted. She it was that stood in Bethlehem on the night when Herod’s sword swept the nurseries of Innocents […] Her eyes are sweet and subtle, wild and sleepy by turns, oftentimes rising to the clouds; oftentimes challenging the heavens.

– Thomas De Quincey, Suspiria de Profundis

I, Varelli, an architect living in London, met the Three Mothers and designed and built for them three dwelling places. One in Rome, one in New York, and the third in Freiburg, Germany. I failed to discover until too late that from those three locations the Three Mothers rule the world with sorrow, tears, and darkness. Mater Suspirorum, the Mother of Sighs and the oldest of the three, lives at Freiburg. Mater Lachrymarum, the Mother of Tears and the most beautiful of the sisters, holds rule in Rome. Mater Tenebrarum, the Mother of Darkness, who is the youngest and cruelest of the three, controls New York.

– From “The Three Mothers” in INFERNO

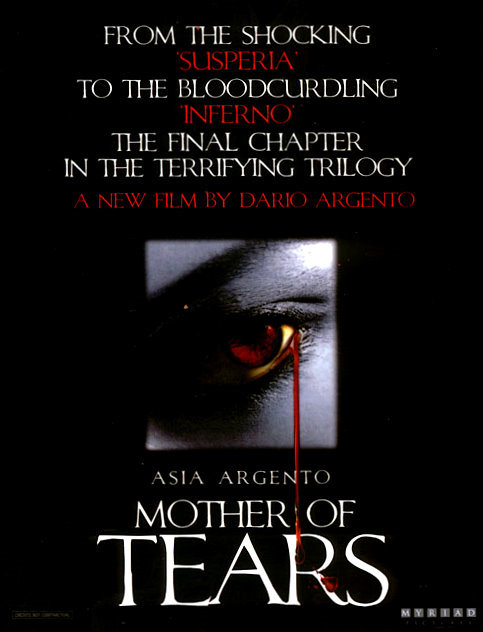

Cinematic horror has a relatively easy time portraying the visceral, but there is more to the genre than Grand Guignol gore. There is also a metaphysical aspect that might, in its simplest formulation, be distilled down to a fairy tale battle between opposing forces of Light and Darkness, Good and Evil. This second aspect of the horror genre is harder to film; after all, how do you photograph an abstraction? (It is obviously much easier to film a knife sinking into a torso.) With SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, Italian filmmaker Dario Argento took a stylized (metaphoric) stab at conveying the unseen presence of “magic…all around us, everywhere,” using deliberately artificial lighting schemes and eccentric camera angles (buildings reflected in puddles, people reflected in buildings) to suggest a parallel world of strange and sinister forces lurking somewhere behind what we call “reality.” THE MOTHER OF TEARS, the concluding chapter of Argento’s “Three Mothers” trilogy, dispenses with the overt stylization of its predecessors (which seemed to take place in some kind of adult fairy tale) in favor of a sobering dose of realism. Ironically, this more prosaic approach turns out to be even more effective at portraying a profound metaphysical horror lurking behind the physical violence on screen. Evil is no longer confined to one of Varelli’s architectural monstrosities; it walks the streets of Rome by daylight, infecting those it touches, creating a eruption of senseless violence that seem to signal the coming of the Apocalypse.

Cinematic horror has a relatively easy time portraying the visceral, but there is more to the genre than Grand Guignol gore. There is also a metaphysical aspect that might, in its simplest formulation, be distilled down to a fairy tale battle between opposing forces of Light and Darkness, Good and Evil. This second aspect of the horror genre is harder to film; after all, how do you photograph an abstraction? (It is obviously much easier to film a knife sinking into a torso.) With SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, Italian filmmaker Dario Argento took a stylized (metaphoric) stab at conveying the unseen presence of “magic…all around us, everywhere,” using deliberately artificial lighting schemes and eccentric camera angles (buildings reflected in puddles, people reflected in buildings) to suggest a parallel world of strange and sinister forces lurking somewhere behind what we call “reality.” THE MOTHER OF TEARS, the concluding chapter of Argento’s “Three Mothers” trilogy, dispenses with the overt stylization of its predecessors (which seemed to take place in some kind of adult fairy tale) in favor of a sobering dose of realism. Ironically, this more prosaic approach turns out to be even more effective at portraying a profound metaphysical horror lurking behind the physical violence on screen. Evil is no longer confined to one of Varelli’s architectural monstrosities; it walks the streets of Rome by daylight, infecting those it touches, creating a eruption of senseless violence that seem to signal the coming of the Apocalypse.

[NOTE: minor spoilers contained herein. Details are vague, but you might be able to figure things out from what is hinted.]

The plot is built around the hoariest of cliches: an ancient urn is accidentally unearthed, containing mysterious objects that empower the Mater Lachrymarum (the Mother of Tears, played by Moran Atias), who has apparently been dormant since INFERNO twenty-seven years previously. A museum assistant, who opens the urn, is brutally murdered by Mater Lachrymarum and a trio of demons. The only witness, Sarah Mandy (Asia Argento), becomes a target. She evades both the police (who want to question her) and the witches (who are arriving at Rome in alarming numbers), while seeking an explanation for what she saw. As riots and random violence spread throughout the city, Sarah tracks down various experts, who fill her in on the back story from the previous films and reveal details connecting her personally to what is happening.

Sarah initially seems to be the archetypal Argento protagonist: an innocent, in the wrong place at the wrong time, who has her eyes suddenly opened to the brutality and horror lurking behind the pleasant facade of normal life. However, a difference soon becomes apparent: Sarah is the daughter of the late Elisa Mandy (Daria Nicolodi), a powerful white witch who decades previously fought and wounded Mater Suspiriorum (the Mother of Sighs), the ancient old crone eventually killed off by Suzy Bannion in SUSPIRIA. This adds an unaccostomed but effective layer of melodrama: Sarah is not merely fighting for her own survival; because of her parentage, she is the only with the power to confront the Mother of Tears. This leads to a wild, orgiastic conclusion in which Sarah (like Suzy in SUSPIRIA and like Mark in INFERNO) must descend through hidden passages into the bowells of the Third Mother’s lair. But what hope does this neophyte witch have of defeating an evil as ancient as time itself?

Sarah initially seems to be the archetypal Argento protagonist: an innocent, in the wrong place at the wrong time, who has her eyes suddenly opened to the brutality and horror lurking behind the pleasant facade of normal life. However, a difference soon becomes apparent: Sarah is the daughter of the late Elisa Mandy (Daria Nicolodi), a powerful white witch who decades previously fought and wounded Mater Suspiriorum (the Mother of Sighs), the ancient old crone eventually killed off by Suzy Bannion in SUSPIRIA. This adds an unaccostomed but effective layer of melodrama: Sarah is not merely fighting for her own survival; because of her parentage, she is the only with the power to confront the Mother of Tears. This leads to a wild, orgiastic conclusion in which Sarah (like Suzy in SUSPIRIA and like Mark in INFERNO) must descend through hidden passages into the bowells of the Third Mother’s lair. But what hope does this neophyte witch have of defeating an evil as ancient as time itself?

Although the plot description may sound uninspired, the experience of watching MOTHER OF TEARS is like a delirious descent into primordial chaos, where the powers of darkness hold sway. Argento has seldom been praised for his storytelling skills, but the critical consensus that he expends his extraordinary visual pyrotechnics on weak screenplays is a bit off the mark. Argento’s approach is essentially an operatic one, in which the libretto serves to link together a series of arias. Instead of fleshing out his stories with the prosaic elements of characterization and plot development, he relies on the visual poetry of cinema, backed by thundering music (in this case by Claudio Simonetti, formerly of Goblin), to create a series of set pieces that convey the “meaning” of the film (whatever that may be).

In MOTHER OF TEARS, this manifests in the form of the most gruesome violence that Argento has ever depicted. In this respect, the film feels like Argento’s equivalent of BAY OF BLOOD, the 1971 proto-slasher film from director Mario Bava, in which the elder statesman of Italian horror proved that he could deliver explicit violence as effectively as any of his young competitors (including Argento himself). Decades later, things have come full circle; now Argento is the elder statesman who has to prove himself the equal of young upstarts, delivering more than enough murder and mayhem to put the purveyors of “Torture Porn” in their place. (The film feels like one, big, long, loud “f.u.” to Eli Roth and company: “You think you’re tough? Well, I’m gonna show you what it’s all about, you bunch of pussies!”)

In fact, the very first murder (which includes broken teeth, a slit stomach, and looping entrails) is so far over-the-top that it very nearly yanks the viewer out of the film; it has the vaguely desperate air of filmmaker trying to shock a restless audience into submission before there is any risk of their growing bored and walking out. After the initial shock of revulsion wears off, we see that this opening (which is clearly meant to top the gruesome first reel of SUSPIRIA – much like the H-bomb makes the A-bomb look like a firecracker) is part and parcel of the new film’s no-holds-barred approach. Argento is not kidding around here; he wants you to feel that you are facing something that is not simply violent but actually off the scales of any conceivable human behavior – a force that glories in death and destruction as if they were joyous pastime to be savored sweetly, with the refined taste of a true aesthete.

In fact, the very first murder (which includes broken teeth, a slit stomach, and looping entrails) is so far over-the-top that it very nearly yanks the viewer out of the film; it has the vaguely desperate air of filmmaker trying to shock a restless audience into submission before there is any risk of their growing bored and walking out. After the initial shock of revulsion wears off, we see that this opening (which is clearly meant to top the gruesome first reel of SUSPIRIA – much like the H-bomb makes the A-bomb look like a firecracker) is part and parcel of the new film’s no-holds-barred approach. Argento is not kidding around here; he wants you to feel that you are facing something that is not simply violent but actually off the scales of any conceivable human behavior – a force that glories in death and destruction as if they were joyous pastime to be savored sweetly, with the refined taste of a true aesthete.

Again and again Argento will push the boundaries of good taste and ruthlessly overturn them. Not only will he top the opening murder in terms of graphic gore (in a deliberately vulgar scene that takes the phallic symbolism of violent penetration to new depths of atrocity); he will go even further in terms of breaking sacred taboos: we all know that sexed-up teenagers and/or naive tourists are fair game, but how many horror films have the nerve to kill off innocent babes? Not one or twice but thrice: one death depicted on screen, another body found in a pool of blood, and a third mercifully assumed as an off-screen event.* This “Slaughter of the Innocents” is like a visual slap in the face to the audience; coupled with the widespread rioting briefly glimpsed throughout the film, it creates an oppressive sense of danger – a world overrun by Evil, where no one is safe.

As effective as the violence is, the film has much more to offer in terms of interesting imagery. Being an Argento film, there are the typically eccentric touches, including Mater Lachrymarum’s monkey accomplice (not a witch’s familiar but an actual witch, if Argento is to be believed in this interview). Fortunately, this primate’s actions are not nearly as ludicrous as those of the chimp in PHENOMENA: occasionally, this well-trained animal actor conveys something like a sinister intelligence. There are other moments when the weirdness packs more punch than visceral bloodshed. Watch Mater Lachrymarum laciviously licking the face of one victim: at first glance, it appears to be a simple stroke of sexual innuendo, a crude way to make the villainess appear revolting, but then you realize that the Mother of of Tears is literally lapping up her the tears of her victim – that is, feeding on the sorrow and pain she creates.

From the opening credits, Argento manipulates these images and symbols like a card-sharp manipulating a deck to create a winning hand: backed by Simonetti’s ominous score, a series of paintings depict Hellish visions of Pandemonium and Sorcery, evoking the infernal powers that will overtake Rome. Against these powerful depictions of Satanic majesty (which become manifest in terms of the violence described above), mere mortals seem helpless, and indeed the side of Good fares poorly. We see various priests, alchemists, and psychics who may have useful bits of information, but they are disorganized, working separately, unable to mount a unified defense against the emerging threat. The world of spirits is invoked, including Sarah’s mother Elisa, but they can offer only limited assistance. In the world of witchcraft and paganism, there are no useful allies who can aid Sarah, and the ultimate battle between Good Witch and Bad Witch is almost a non-starter. In the end, it is Christian imagery that offers the only salvation. When Detective Marchi (the aptly named Cristian Solimeno) is captured and virtually crucified (down to having a spear impaled in his chest), it is his blood, falling from his head as if from a crown of thorns, that will “resurrect” the unconscious Sarah, giving her one last chance to deliver the coup de grace to the apparently triumphant Mater Lachrymarum.

Despite this virtuoso tour de force– and many others like it (including a nifty “invisiblity” scene achieved not with CGI but with clever staging and camera angles) – MOTHER OF TEARS has not earned universal adulation from fans of SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, who wanted more of the same, instead of the radically different approach on display here. Argento’s concluding chapter of the “Three Mothers” trilogy parallels producer-director Roger Corman’s final Poe film, THE TOMB OF LIGEIA (1965). Up to that point, Corman’s Poe series (which influenced SUSPIRIA) were deliberately artificial, usually limited to one isolated setting (an old mansion or a castle) that was rendered in almost expressionistic terms with sets and lighting meant to convey not physical reality but the inner psychological state of the decaying lead characters; this approach extended to the exteriors, which were often filmed on sets or used matte paintings to create a dreamy Gothic ambiance. LIGEIA broke with that tradition, using beautiful location photography that took the horror out of the shadows and put it into something resembling the real world. Argento does something similar here, setting the horror (as he told me) “in the real world […] in the airports, in the train station, on the streets – everywhere.” Those looking for another excursion into a mesmerizing fantasy land of fairy tale dangers would inevitably be disappointed.

There are other reasons to be disappointed. Chief among these is actress Moran Atias. She cuts a striking figure in the title role, but her acting evokes unwanted memories of Michell Bauer in just about any Fred Olen Ra exploitation opus – which is to say that her seductive look is the performance, and that’s about it. Hopefully, the audience (at least the men) will be distracted by the sight of her naked body and not worry too much about the dialogue, whether in English or Italian.

The early scenes of unearthing the urn look lackadaisical; showing little sign of Argento’s usually vivid visual skills, they might as well have been directed by a second unit team. (They are hardly aided by the bad dubbing of the English-language print.**) Later, a flashback explaining the history of the urn is rendered in drawings instead of live action (presumably for budgetary reasons). The ending does not offer the promised pay-off. After all the talk of Sarah’s having inherited her mother’s powers, you might be expecting a final duel depicting the powers of sorcery, realized with high-tech visual effects, but you would be wrong.

On a plot level this makes sense: Sarah has not had time to train herself to use her new-found powers, but one cannot help wishing for a MATRIX-style ending in which she suddenly, intuitively masters her arts and goes mano-a-mano with her opponent. Instead, the ending suffers from a flaw that marred SUSPIRIA and INFERNO, in which monstrous evil seems peculiarly vulnerable once its hiding place has been discovered. On top of that, the final image borders on the risible. (Jessica Harper’s smile of relief at the end of SUSPIRIA was a model of subtlety by comparison.)

At least Sarah’s witch powers do serve one function. In the time-honored tradition of horror films, she receives a Final Girl dispensation that allows her to survive while everyone around her is viciously cut down. Audiences are trained to accept this kind of thing as a a piece of dramatic license, but here we know that Sarah’s status as a white witch, aided occasionally by the spirit of her mother, is keeping her alive.

Elisa Mandy’s ghostly materialization is conveyed with some nice if not entirely convincing computer-generated imagery. In other cases, CGI is to compliment the prosthetic effects, taking gore to new levels. (Well, maybe not exactly new: Argento previously filmed a pointed stake bursting from a victim’s mouth in his “The Black Cat” episode of TWO EVIL EYES. However, the digitally enhanced version in MOTHER OF TEARS is more effective.) There is also a brief, startling moment when one of Mater Lachrymarum’s henchmen stretches his face into a furious roar, jaw dropping impossibly low. To U.S. viewers, this may look like a rip-off of I AM LEGEND, but MOTHER OF TEARS was actually released in Italy six weeks before the Will Smith film made its debut in the U.S. More significantly, Argento uses the effect only once, for its shock value, instead of overusing it to the point where it becomes ridiculous.

As a long-awaited coda to Argento’s “Three Mothers” trilogy, THE MOTHER OF TEARS may not be exactly what was expected, but it is perfectly satisfying resolution (at least to viewers not demanding a retread of the previous films). Although the continuity is occasionally fudged (Mater Lachrymarum has lost her affection for cats, seen in INFERNO), the screenplay works hard to weave together leitmotivs from its predecessors. The effect is enhanced by casting that feels like a reunion of old friends and family. Udo Kier is memorable as an aging exorcist; although playing a different character than in SUSPIRIA, his plot function is, amusingly, to provide the back story of the Mother of Sighs, who featured in that film. As in INFERNO, there is a wheelchair-bound alchemist (albeit played by a different actor), who shows Sarah in a copy of the book that featured so prominently in the first sequel. And Argento’s one-time domestic partner Daria Nicolodi (who appeared in INFERNO) is back on board as Elisa – which is only fair, considering that she helped create the trilogy by co-writing SUSPIRIA. She does not get that much to do, but her mere presence is plus.

Argento has never been singled out for his sensitive handling of actors, but the performances here are actually good, if occasionally over the top. In the lead, Asia Argento suffers far less humiliation and degradation than her father dished out to her in previous films, particularly THE STENDAHL SYNDROME (although he still has her perform a nude scene). It is hard to say whether Asia is a truly gifted actress, but she has an interesting look – not only attractive but insolent and vaguely troubled – that makes her interesting to watch even when there is no depth to the character. Likewise, Solimeno has little to work with as the typical cop character (who shows up in most Argento films), but his good looks and charisma are enough to hold attention when he is on screen. Adam James, as Sarah’s love interest, is essentially playing a plot device (he advances the story in the early scenes before Sarah is capable of taking over), but the English actor adds a layer of humanity that generates a little audience sympathy.

Even better is Valerai Cavalli as psychic Marta Colussi. In a film where each stranger could be a threat, she emits a comforting warmth that is immediately endearing. Her character also happens to be – in the great tradition of Eurotrash cinema – a lesbian; fortunately, this turns out to be the least exploitative element of the film. Unlike the virtual cartoon characters Argento killed off in TENEBRE, Marta and her partner are a believable couple, both of whom just happen to be lovers, and their brief bedroom scene is filmed with what can only be called sensitivity: it really looks like love-making, not a guy’s fantasy of hot girl-on-girl action.

In a small role as a witch, Japanese expatriate actress Jun Ichikawa is a standout, far outshining Atias in terms of projecting evil; Ichikawa may not be Argento’s idea of the “most beautiful of the sisters,” but she would have made a much more convincingly evil Mater Lachrymarum. Argento probably had other things on his mind. Just as his use of violence seems to be a riposte to Torture Porn, the fate accorded to Ichikawa’s character seems to be the director’s comment on the popularity of J-Horror films like JU-ON: THE GRUDGE, which deliberately mimics the loosely connected plot structure of INFERNO.

In a small role as a witch, Japanese expatriate actress Jun Ichikawa is a standout, far outshining Atias in terms of projecting evil; Ichikawa may not be Argento’s idea of the “most beautiful of the sisters,” but she would have made a much more convincingly evil Mater Lachrymarum. Argento probably had other things on his mind. Just as his use of violence seems to be a riposte to Torture Porn, the fate accorded to Ichikawa’s character seems to be the director’s comment on the popularity of J-Horror films like JU-ON: THE GRUDGE, which deliberately mimics the loosely connected plot structure of INFERNO.

Once all the dust has settled – and the blood has dried and the open wounds have healed – what remains is that MOTHER OF TEARS succeeds in taking cornball cliches and bringing them to convincing life. When a wounded victim, lying on the floor, realizes she is in the presence not just of a human killer but of the Mother of Tears herself, the moment of recognition could have been – indeed, should have been – merely silly, an out-dated melodramatic flourish worthy of a second-rate adventure serial. Instead, Argento sells the scene with utter conviction.

This is the saving grace that obscures (if not quite erases) the film’s flaws: Just as STAR WARS graciously allowed you to once again to boo and hiss the villain without feeling embarrased for indulging in the childish emotional response, MOTHER OF TEARS invites you to shiver in the presence of Evil with a capital E. In SUSPIRIA, Udo Kier’s psychiatrist character told us that bad luck comes not from broken mirrors but broken minds. The whole of the “Three Mothers” trilogy contradicts this assertion, nowhere moreso than in MOTHER OF TEARS, where Kier, now playing a priest, tells Sarah, “There is nothing wrong with your mind. The world has gone mad.” Bad luck, we see, brims up from the very bowels of Hell, and if we are not careful – or blessed, or merely fortunate – it will consume us all.

THE MOTHER OF TEARS (a.k.a. La Terza Madre [“The Third Mother], 2007). Directed by Dario Argento. Written by Dario Argento, Jace Anderson, Adam Gierasch, Walter Fasano, Simona Simonetti. Cast: Asia Argento, Cristian Solimeno, Adam James, Moran Atias, Valeria Cavali, Philippe Leroy, Dario Nicolodi, Coralina Cataldi-Tassoni, Udo Kier, Robert Madison, Jun Ichikawa, Tommaso Banfi.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Interview: Dario Argento sheds the Mother of All Tears

- Cybersufring: Lambs to the Slaughter

- Book Review: Suspiria de Profundis

- Film Review: Suspiria

- Film Review: Inferno

*Actually, this death may not be off-screen. There is a shadowy cannibalistic orgy glimpsed in the lair of Mater Lachrymarum; although the victim is not clearly seen, it could easily be the missing child whose death is later assumed by its father.

**The bad dubbing afflicts mostly this opening scene, plus some crucial moments at the conclusion. The majority of the film appears to have been shot in English with the principal players speaking their own dialogue; only the supporting cast was obviously dubbed. The worst example is one of Mater Lachrymarum’s imposing acolytes, who speaks with a laubhably bad cartoon voice.

8 Replies to “Mother of Tears (2007) – Film Review”