This is Hammer Films’ first sequel to 1958’s HORROR OF DRACULA to feature the return of Christopher Lee as the Count (who was notably absent from 1960’s THE BRIDES OF DRACULA). It is also the last Dracula film helmed by their top in-house director, Terence Fisher, who was the man behind the camera for most of their classic films in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Made at a time when Hammer was searching for new ideas to keep their horror franchise alive, it is part of a second wave that briefly reinvigorated the studio before it gradually descended into rehashing its familiar fiends. The productions values and the performances are as strong as ever, and the script does an imaginative job of resurrecting Dracula, but the film is not quite up to the level of its predecessor, the latter half turning into a bit of a mechanical thriller (albeit still an exciting one).

This is Hammer Films’ first sequel to 1958’s HORROR OF DRACULA to feature the return of Christopher Lee as the Count (who was notably absent from 1960’s THE BRIDES OF DRACULA). It is also the last Dracula film helmed by their top in-house director, Terence Fisher, who was the man behind the camera for most of their classic films in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Made at a time when Hammer was searching for new ideas to keep their horror franchise alive, it is part of a second wave that briefly reinvigorated the studio before it gradually descended into rehashing its familiar fiends. The productions values and the performances are as strong as ever, and the script does an imaginative job of resurrecting Dracula, but the film is not quite up to the level of its predecessor, the latter half turning into a bit of a mechanical thriller (albeit still an exciting one).

After a prologue that features the Count’s demise from HORROR OF DRACULA (reflected in the misty surface of a mirror, to help cover the fact that the old footage is in standard format while the new footage is widescreen), the story picks up with a pair of English couples vacationing in Transylvania. Mishaps lead them to Castle Dracula, where the Count’s servant Klove (a deadpan ghoulish Philip Latham) kills one of the men to use his blood to revive the vampire. Dracula then vampirizes the dead man’s wife, while the other couple manages to escape to a monastery presided over by Father Sandor (Andrew Keir), who helps them defeat Dracula, fending him off when he invades the monastery and tracking him back to his castle, where he sinks into the running waters of his moat.

The new film makes excellent use of widescreen photography to show off the beautiful sets. The format seems perfect for director Terence Fisher, who often avoided fancy camera moves and montage in favor of letting his actors move about the frame, performing separate actions in the foreground, background, left, or right. In one of the film’s moody highlights, Fisher even manages to suggest the unseen spirit of the departed Dracula with a few simple tracking shots down empty hallways, brilliantly foreshadowing the Count’s eventual return.

The first half of the story has a built-in hook: how will the film bring back Dracula (who was turned to dust at the end of HORROR OF DRACULA). The answer is fairly ingenious, with Klove killing one innocent victim and stringing up his body over the Count’s coffin with all the solemnity of a religious sacrifice. The scene of blood dripping onto the ashes turned a few stomachs in its day, and the special effects that follow are nicely done in a subtle way (a layer of mist obscures details of the body’s reformation). In a nice touch of — shall we call it realism? — Dracula is not reborn fully clothed; instead, his servant has a new suit waiting for him (this also explains any change in the Count’s attire from the first film to this one).

The first half of the story has a built-in hook: how will the film bring back Dracula (who was turned to dust at the end of HORROR OF DRACULA). The answer is fairly ingenious, with Klove killing one innocent victim and stringing up his body over the Count’s coffin with all the solemnity of a religious sacrifice. The scene of blood dripping onto the ashes turned a few stomachs in its day, and the special effects that follow are nicely done in a subtle way (a layer of mist obscures details of the body’s reformation). In a nice touch of — shall we call it realism? — Dracula is not reborn fully clothed; instead, his servant has a new suit waiting for him (this also explains any change in the Count’s attire from the first film to this one).

There are some nice thematic ideas underlining the action. The sacrificial victim and his wife are an uptight, repressed couple, which apparently makes them more vulnerable to Dracula’s allure. In a sense (as David Pirie points out in A Heritage of Horror), they are reborn as Dracula and his vampire bride — their bloodlust a dark inversion of their former prudery.

There are some nice thematic ideas underlining the action. The sacrificial victim and his wife are an uptight, repressed couple, which apparently makes them more vulnerable to Dracula’s allure. In a sense (as David Pirie points out in A Heritage of Horror), they are reborn as Dracula and his vampire bride — their bloodlust a dark inversion of their former prudery.

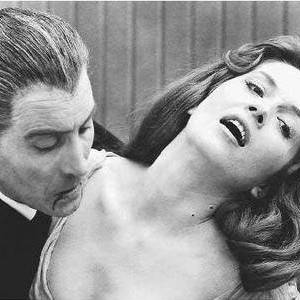

Unfortunately, once the resurrection of Dracula has been achieved, the film does not know what to do with him, except have him pursue the film’s other female lead back to the monastery. Despite the “Prince of Darkness” phrase used in the film’s title, the Count is never seen engaged in any major metaphysical evil; he acts mostly like a snarling if seductive animal. In fact, Dracula speaks not a word of dialogue, leaving all the talking to his servant and to Barbara Shelley as the victim-turned-vampire. Even without words, Christopher Lee manages to give a powerful performance, commanding and imposing. Andrew Keir as Father Sandor is a strong substitute for Doctor Van Helsing. Francis Matthews and Suzan Farmer are appealing as the young couple. But the real standouts are Latham and Shelly.

Despite the weaknesses in the story, the second half of the film includes numerous memorable scenes. In one lifted from the book, Dracula opens a vein in his chest and tries to force Farmer’s young ingénue to drink his bodily fluids. Filmed in close-ups that hide the relative position of her head to Lee’s body, the scene is loaded with suggestions or forced oral sex (which is quite amusing when seen on afternoon television).

Despite the weaknesses in the story, the second half of the film includes numerous memorable scenes. In one lifted from the book, Dracula opens a vein in his chest and tries to force Farmer’s young ingénue to drink his bodily fluids. Filmed in close-ups that hide the relative position of her head to Lee’s body, the scene is loaded with suggestions or forced oral sex (which is quite amusing when seen on afternoon television).

Even better is the staking of Shelley’s she-vampire, which takes place in the monastery, presided over by Sandor. The remarkable element of the action is that it takes place at night, with the vampire fully conscious and struggling on a table, while four monks hold her limbs down. Although the dialogue tells us that Sandor and his monks are performing a service to save the woman from the vampire’s curse and set her spirit free, the action plays out like a gang rape, with the helpless woman brutalized by a group of heartless men.

The ending is slightly less spectacular than that of HORROR OF DRACULA, with the Count slipping through broken ice to be swallowed up by the running waters of the moat around his castle, but the idea is at least loosely derived from Stoker’s novel (in which vampires can cross running water only at high and low tide). The imagery is actually fairly powerful, and it is one of the few moments that live up to the satanic implications of the film’s title. As Dracula tries to save himself, his fingers grasp the edge of the ice harder, which dooms him to sink faster as the ice melts beneath his grip. The scene seems intentionally reminiscent of the ending of Dante’s Inferno, which shows Satan trapped in the ice in the lower pit of hell, his wings flapping in a vain effort to pull him free, their icy breeze only freezing the ice that holds him more firmly, ensuring that he will never escape.

The ending is slightly less spectacular than that of HORROR OF DRACULA, with the Count slipping through broken ice to be swallowed up by the running waters of the moat around his castle, but the idea is at least loosely derived from Stoker’s novel (in which vampires can cross running water only at high and low tide). The imagery is actually fairly powerful, and it is one of the few moments that live up to the satanic implications of the film’s title. As Dracula tries to save himself, his fingers grasp the edge of the ice harder, which dooms him to sink faster as the ice melts beneath his grip. The scene seems intentionally reminiscent of the ending of Dante’s Inferno, which shows Satan trapped in the ice in the lower pit of hell, his wings flapping in a vain effort to pull him free, their icy breeze only freezing the ice that holds him more firmly, ensuring that he will never escape.

Whatever the flaws that prevent it from fully achieving classic status, DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS is probably Hammer’s last great Dracula film — a solid, sometimes imaginative effort that remains exciting and entertaining even after its best ideas have run out. Although it is easy to imagine a better film (one that gives Dracula more opportunity to live up to the sobriquet “Prince of Darkness”), the film as it exists now is one of the best cinematic vampire efforts and probably deserves to rank above BRIDES OF DRACULA (in spite of critical consensus to the contrary).

TRIVIA

In a belated nod to Bram Stoker’s novel, the film introduces us to Ludwig, a lunatic loosely inspired by Renfield. Although well played by Thorley Walters, the character fails to live up to his inspiration. Mostly he serves as a plot device: as in the book, vampires cannot cross a threshold unless invited inside; Ludwig is the one responsible for inviting Dracula into the monastery.

The screenplay is credited to “John Samson,” a pseudonym for Jimmy Sangster (who previously scripted HORROR OF DRACULA). Sangster was reportedly unhappy with changes made to his script and therefore removed his name from the final credits.

Christopher Lee has said that Dracula remains mute because the actor refused to speak the dialogue in the script. Some people have theorized that this may be the reason for Sangster’s objection to the finished film. However, no one has ever found a draft of the screenplay with dialogue for Dracula; today, the consensus is that the Count was always intended to remain mute, as he did throughout the later portions of HORROR OF DRACULA.

Although the interior of Dracula’s castle looks similar in its decor to that seen in HORORR OF DRACULA, the layout is clearly different.

DRACULA, PRINCE OF DARKNESS was shot back-to-back with RASPUTIN, THE MAD MONK. Much of the cast reappears (including Christopher Lee in the title role), and many of the sets were re-used. In fact, RASPUTING plays fairly fast and loose with historical authenticity, portraying the monk as someone with hypnotic powers similar to Dracula’s.

Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1965). Directed by Terence Fisher. Screenplay by “John Samson” (Jimmy Sangster), from a story by John Elder (Anthony Hinds). Cast: Christopher Lee, Barbara Shelley, Andrew Keir, Francis Matthews, Suzan Farmer, Charles Tingwell, Thorley Walters, Philip Latham