An affection tribute to one-half of the team that brought some of the movies’ most memorable monsters to life

“Some people say Casablanca or Citizen Kane. I say Jason and the Argonauts is the greatest film ever made.”

Tom Hanks affectionately spoke these words while on stage at the 1992 Academy Awards ceremony for science and technology. It seemed fitting for him to be there and to speak as he did. After all, it was that film and the people behind it which made him want to become an actor.

Although the popular main figure behind the iconic piece of cinema was Ray Harryhausen, and the person for whom Mr. Hanks was at the ceremony to honor, there was another person heavily involved in its production, someone who was with Ray practically from the beginning of some highly influential motion picture history. He was Charles H. Schneer. His may not be a household name, but the films he made with Harryhausen stirred the imaginations of at least three generations and ignited a passionate flame within innumerable young souls – souls who would move and shake the visual effects industry.

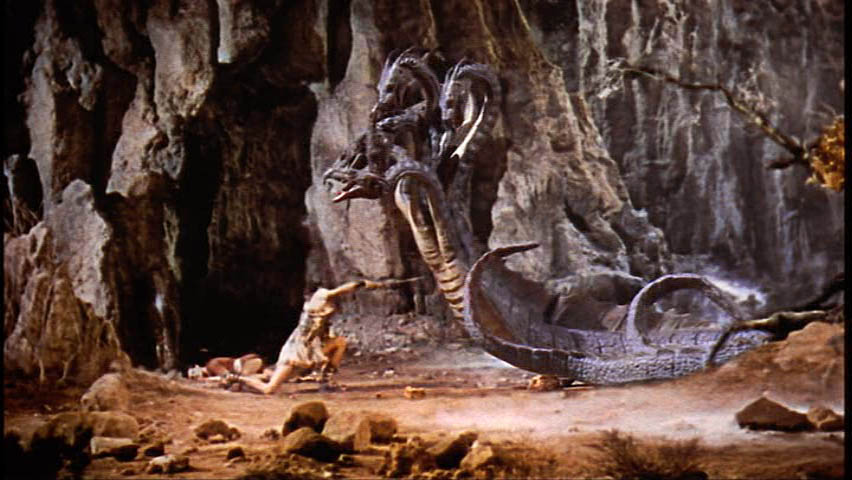

That half of a salient team passed away in Boca Raton, Florida on January 21, 2009. He was 88. Together, Schneer and Harryhausen (who were born the same year) took millions of viewers on voyages of wondrous, dreamy imagination. With them, youngsters around the world fought giant bronze Titans, seven headed Hydras, one-eyed Cyclopes, Medusa, and even a horde of skeletons! They were practically inseparable in their work and one wonders, without each one would there have been a complete other?

At the time the potential production of one of their most successful and most fondly remembered films, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, came along Schneer and Harryhausen had already worked together thrice before. All three low-budget films had turned tidy profits, but even with these recent successes under his belt, Harryhausen’s Arabian Nights pet project was turned down by several studios. But in stepped an interested party: Charles Schneer. “Ray had done these absolutely splendid charcoal drawings,” said the producer. “I thought they were the most unusual visuals I’d ever seen. I was swept off my feet by the images they conjured up. But all Ray had were these spectacular drawings. He didn’t have a story. So I hired a writer named Kenneth Kolb, and together we built a story line around Ray’s drawings.”

It was also at this time that Schneer—in a clever turn of showmanship—coined the term ‘Dynamation,’ (later also known as ‘Dynarama’) partially to separate in the mind of the public Harryhausen’s unique work style from other forms of animation. “The ‘mation’ suffix comes from ‘animation,’ of course,” Schneer reminisced. “I knew it needed something to go with it.’Dyna’ came from a Buick I once owned, which had the word ‘Dynaflow’ printed on the dashboard. The term ‘Dynamation’ had never been used before, so I immediately patented it. That’s one word we put into the film business.”

You might say that in a sense, Schneer was a modest-budget George Lucas to Harryhausen’s Steven Spielberg. Both men were deeply involved in all aspects of their films. Schneer provided the means, the support, and extra inspiration, while Harryhausen provided much of the creative elements. They made a well matched team—one needed the other in order to create a cohesive and successful whole—and it remains a bit confusing as to why Schneer is a mere and minor afterthought. He is little known for his efforts or his loyalty to the genre he helped propel forward. There is something very sad in that.

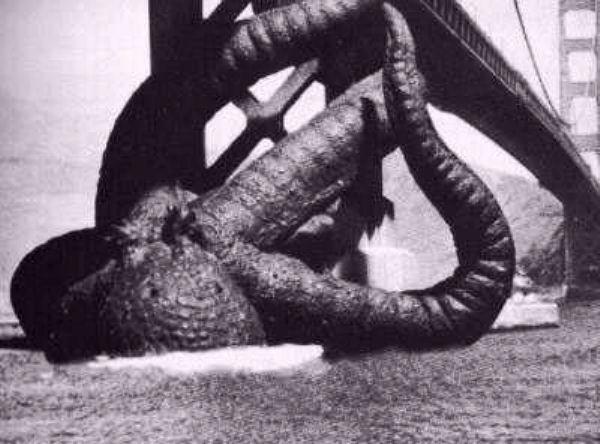

Mr. Schneer sole-produced his first film in 1955 (under the Columbia Pictures banner, for which he worked). Rather prophetically, it was the first of the aforementioned films, It Came from Beneath the Sea and would be a Harryhausen effort. A year later both men teamed up a second time on the rather unique and gutsy effects endeavor, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers. And in the next year they sent a Venusian creature on a trip that would be 20 Million Miles to Earth.

But something different had occurred in relation the production of 20 Million Miles to Earth. Schneer had decided to go solo as a producer and moved away from Columbia Pictures and his long-time boss and mentor of sorts, producer Sam Katzman, to set up his own production company called Morningside Pictures. This move would come to allow Schneer and Harryhausen a sense of autonomy concerning their films.

Interestingly, though, Harryhausen didn’t immediately think of Schneer when he was finding himself in a state of rejection time and again whilst trying to get his Sinbad project off the ground. But while all that was going on Schneer had made an advantageous arrangement with Columbia that allowed him deeper access to the studio’s costumes and sets and generally gave him a bit more money and material with which to work. The planets must have been aligning just right, for it was about at this time that Harryhausen’s project came across his desk. With Schneer’s immediate interest in it, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad became the fourth Schneer/Harryhausen collaboration. And with that, it seems an historic film union had been decreed unbreakable by the film Gods.

The duo wound up making no less than 12 movies together. Schneer produced nearly all of Harryhausen’s work, except for Animal World (which actually came not long after It Came from Beneath the Sea and was an early Irwin Allen production that wound up landing on the ash heap of history) and Hammer Films’ One Million Years B.C. (that film was as famous for what Rachel Welch’s costume did for her fame as for anything Harryhausen did).

The two men understood each other, worked well together, and from that time on they would be nearly inseparable partners. They would go on to create eight more projects together: some that were held dear to fans (Mysterious Island, The Valley of Gwangi), and some that were bitter disappointments (Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger – though less due to Harryhausen’s work than to the horrendous storyline and overall execution).

It was in 1962 that the two would make what is considered their genre masterpiece, Jason and the Argonauts (originally titled “Jason and the Golden Fleece”). And for the first time Harryhausen asked for an official associate producer credit. This had much to do with the fact that the project was an original idea of Harryhausen’s and he was crucial to the design and execution of the picture. Schneer was more than willing to give him the title, saying later, “Actually, it was long overdue. Ray asked for that credit, and I had no problem with it. If he wanted it, he could have it.” Harryhausen would also be credited as associate producer for First Men in the Moon and The Valley of Gwangi; on all of their subsequent projects together he would receive equal billing as producer.

Harryhausen had a wonderful talent and was able to work in a disciplined fashion, but that in itself was not enough to ensure a successful career in his area of expertise. Demonstrative of this are the likes of the great American pioneer of stop-motion animation, Willis O’Brien (whose 1933 King Kong is one of the most admired and successful films of all time), and individuals like Art Clokey (who did find success on the small screen with the simple settings of the low-budgeted Gumby series), Peter Kleinow (who worked with Clokey for a time), Jim Danforth (who has kept busy over the years, but still seems to be known for his work on the soft-porn sci-fi spoof, Flesh Gordon) and David Allen (also known partially for his work on Gordon, in addition to the prehistoric dino-spoof Caveman). Talented men all, but none had a strong producer and supporter like Charles Schneer to fully propel their work into the public consciousness.

Allen, for example had a project that he’d been trying to get off the ground for years. Finally, in 1978 he began production on it with producer Charles Band. The film was the subject of a cover story in Cinefantastique Magazine that year, but despite the interest, the production was shut down. Examples like this are why the importance of Schneer’s contribution to Harryhausen’s success, as well as the fantasy & science fiction film genre, and film history itself, should not be undermined. He was a man who had illusory prowess, like his partner, and he knew his business.

Producer Paul Maslansky (Damnation Alley, Return to Oz, the Police Academy films,), who began his career with Schneer, once said of the seasoned producer, “Charlie was very particular about things. He was from the old Harry Cohen tradition; though much nicer, from what I hear about Cohen. His methods often weren’t exactly the way mine would be, but the biggest lesson I learned from Charlie was being tenacious, persistent. His brief was to make movies economically. If he got ‘No’ for an answer, he’d find another way of asking the question. That first price you get from someone is not necessarily the best price. You negotiate with technicians, with actors, everyone. Negotiate with strength, to find a better price, then hold up your end of the bargain. He taught me to be specific, not vague. Have facts and figures to back up your pitch. Don’t just say, ‘Oh, I think we’d need about six weeks to make this picture.’ Never be abstract. Have everything broken down; figures and boards, and say, exactly, ‘Here’s our schedule. We need precisely this much money and this much time.’” Schneer was a man who could make things happen in a tough industry—and he could do so on affordable budgets. It was why he was able to continue making fantasy films while the efforts of many others stalled.

Schneer produced several films unrelated to Harryhausen over his near three-decade long career (Half a Sixpence, Good Day for a Hanging, Hellcats of the Navy – with future president, Ronald Reagan), but it seems fitting that 1981’s Clash of the Titans would be his—and, up to now, Harryhausen’s—last film. Both men essentially retired after that (though Harryhausen is reported to be serving as a producer for an old Merion C. Cooper story, titled War Eagles, set for a 2010 release). Titans was one of Schneer’s most ambitious projects, attracting some of the most respected actors in film, with Sir Laurence Olivier, Maggie Smith, Burgess Meredith and Claire Bloom among them. A remake of the film is currently in progress, with a screenplay penned by Lawrence Kasdan (The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark).

Mr. Schneer truly was a pioneering and visionary producer within the fantasy & science fiction genre. Harryhausen understood this better than anyone, writing in the preface of his book with film historian & archivist Tony Dalton, Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life, that Schneer was the “the unsung hero” of their films and Harryhausen’s own career. “He is a man I respect immensely. …He would supply the practical element, backed up with copious amounts of memos, and always knew what would work and what wouldn’t,” wrote Harryhausen. “Without his help and foresight, much of what we planned together would not have seen the light of day. …Thank you, Charles.”

The projects he and Harryhausen generated together inspired many of cinema’s greatest artisans: George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson, Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, Rick Baker, John Dykstra Richard Taylor and, yes, Tom Hanks, to name just a few. These individuals are giants in their fields, and Schneer had a noteworthy, albeit indirect, hand in that. He has essentially been relegated to two-sentence footnotes in film history; however, he deserves far more recognition for what he helped make possible. And though Charles H. Schneer has largely remained a man in shadows, he is an important part of cinematic annals and someone of whom we should take note. I, for one, will miss his presence on this little dust ball of ours.

Filmography of producer Charles H. Schneer

- Clash of the Titans (1981)

- Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977)

- The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1974)

- The Executioner (1970)

- Land Raiders (1969)

- The Valley of Gwangi (1969)

- Half a Sixpence (1967)

- You Must Be Joking! (1965)

- First Men in the Moon (1964)

- East of Sudan (1964, executive producer – uncredited)

- Jason and the Argonauts (1963)

- Siege of the Saxons (1963 – uncredited)

- Mysterious Island (1961)

- Wernher von Braun (a.k.a., I Aim at the Stars – 1960)

- The Three Worlds of Gulliver (1960)

- Good Day for a Hanging (1959)

- Face of a Fugitive (1959 – executive producer)

- Battle of the Coral Sea (1959)

- The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958)

- The Case Against Brooklyn (1958)

- Tarawa Beachhead (1958)

- 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957)

- Hellcats of the Navy (1957)

- Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956)

- It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955)

- The 49th Man (1953 – associate producer)

Note: Ted Newsom kindly offered some statistical information in relation to this article.