It’s not easy being the self-proclaimed King of the World. How do you live up to the grandiosity of your own proclamation, after captaining TITANIC (1997) not only to the top of the all-time box office chart but also to multiple Oscar wins, including Best Picture and Best Director? The simple law of averages, the ebb and flow of life, with its inevitable ups and downs, almost assures beyond doubt that your next film cannot possibly top its predecessor and will, most likely, be perceived as a disappointment.1 If you’re James Cameron, and you’ve tucked away enough money to support yourself for a decade, you take so much time getting your next feature film to the big screen that, when it finally arrives twelve years later, it is virtually a come-back effort. This clever career move allows AVATAR to be judged as it deserves to be – on its own considerable merits, rather than a follow-up to the biggest blockbuster ever made.

AVATAR is an enormously entertaining piece of screen spectacle that goes a long way toward redeeming the somewhat debased concept of a Hollywood blockbuster: It is epic in scale and lavish in production, filled with qualities that can only be purchased with big bucks, and yet it never feels like a hollow money pit. It is loaded conventional commercial elements guaranteed to sell tickets worldwide, yet it does not feel “targeted” in the sense of simply throwing in a sop here or there to a particular demographic, regardless of whether it improves the film as a whole. Its scenario is built around familiar and easily accessible storytelling tropes, yet the film never feels dumbed-down or calculated. And though there may be merchandising tie-ins (including a videogame), AVATAR feels like a self-contained entity with its own internal integrity, not a two-hour-plus commercial.

In short, AVATAR aptly demonstrates the difference between Cameron and, say, Roland Emmerich: both are capable of piecing together the elements required to create a box office blockbuster, but Cameron knows how to make the result look like a seamless whole, conceived and painted on a canvas of its own dimensions, rather than a jig-saw puzzle of bits cut to fit together into a pre-sized frame.

WHITE MAN’S BURDEN

The story focuses on Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), a paraplegic former marine who takes the place of his dead brother on a scientific mission on another planet, Pandora. The goal of the mission is to win the hearts and minds of the local population (the Na’vi) by interacting with them through “avatars” – bodies genetically engineered from a combination of human and Na’vi DNA. Jake, being an identical twin, is a perfect match for the avatar that was created (at great expense) for his late brother; also, being new to the mission, he is completely ignorant, which allows Cameron to fill him – and thus the audience – in on the details.

It soon becomes apparent that the Avatar project is a lame duck. Project leader Dr. Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver) may legitimately want to establish peaceful communication with the Na’vi, but the economic interests funding the project have other priorities, namely mining a mineral (rather goofily called “unobtanium” – a pun so bad you expect it to be explained away as a bad joke by the characters). If Dr. Augustine can get the Na’vi to move out of the way, fine, but the working assumption is that the ultimate solution will be enforced relocation if not outright genocide.

As you can probably guess, the film follows Sully’s path from being a disinterested grunt to being reborn as a native sympathizer with a reverence for the natural wonders of Pandora. It is only here, in the thematic aspects of Sully’s journey, that Cameron flirts with disaster. Success in Hollywood – and the freedom that comes with it – often leads to pretension; it’s as if a filmmaker feels the need to justify huge ticket sales by proving he has something to say. Cameron is certainly no stranger to this syndrome, as the THE ABYSS (1989) showed (even TERMINATOR 2 couldn’t help getting a little preachy, with its talk of men creating evil things like SkyNet because they were incapable of creating life – i.e., giving birth – like a woman). In AVATAR, Cameron once again preaches an ecological theme with little subtlety; fortunately, here the alien setting – and the computerized special effects – help sell his message.

Other critics have already noted the similarity to 1990’s Best Picture DANCES WITH WOLVES (underlined by the casting of Wes Studi as the leader of the Na’vi). AVATAR is another film about a white man who “goes native” and switches sides – a theme also explored in DISTRICT 9, earlier this year. Interestingly, unlike Wikus in DISTRICT 9, Sully does not start out as a racist who hates the alien “other”; he’s just doing his job, gathering information that will help the inevitable military solution go more smoothly, in exchange for a promise of having his legs restored. (We are told that this type of surgery is easily within grasp of medical science but outside the pay range of a working soldier – or in this case, mercenary.)

Among other things, what these films have in common is a tendency to invert the cliche: instead of portraying the “other” (be it an alien or an Indian) as a utterly despicable, they are idealized as utterly righteous. Thus, in AVATAR, the Na’vi (who clearly stand in for Native Americans or any other indigenous people threatened by technologically advanced invaders) may be “primitive” in their use of tools, but they are morally advanced, clearly superior to the humans in every way. Not only are they tree-worshippers motivated by spirituality rather than greed; they don’t suffer from any of the less savory aspects one might expect to see in a small, tight-knit tribal community with a single over-powering belief system. (Although there appear to be gender roles in the leadership, there is little evidence of overt sexism, with women warriors taken for granted. There is also little sign of internal dissent, nor any hint of free-thinkers being persecuted for questioning their leaders, whose pronouncements are basically accepted as if they were the Word of God.)

In other words, once Sully’s mind enters his Avatar body, there is almost literally no reason for him not to join up with the Na’vi. His switch is less a choice than an inevitability, pre-determined by Cameron’s screenplay, which could easily be faulted for the simplicity of its presentation – and in fact has been, in a thoughtful review by Annalee Newitz, titled “When Will White People Stop Making Movies Like AVATAR?”

Newitz objects to the familiar scenario: a white man, burdened by guilt, learns the errors of greedy capitalist ways and leads the oppressed racial minority to victory. In her estimation, this is simply a gloss on the old fantasies of colonization:

Sure, Avatar goes a little bit beyond the basic colonizing story. We are told in no uncertain terms that it’s wrong to colonize the lands of native people. Our hero chooses to join the Na’vi rather than abide the racist culture of his own people. But it is nevertheless a story that revisits the same old tropes of colonization. Whites still get to be leaders of the natives – just in a kinder, gentler way than they would have in an old Flash Gordon flick or in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars novels.

Seen in these terms, AVATAR is guilty as charged. Although Cameron treats corporate greed – as practised by white men – as unambiguously evil, he still focuses on a white male hero who is better at being a Na’vi than the Na’vi themselves and who ultimately saves them when they are incapable of saving themselves.

However, two points are worth making in AVATAR’s defense:

First, the film presents Jake not just as a heroic leader but also as a symbol who inspires the Na’vi to realize what they are capable of. The man himself, to a certain extent, is less important than the way he is perceived. Jake himself realizes that he, alone, is not enough to tip the balances – which is why he hitches a ride on the Great Leonopteryx, a task previously achieved only in legends of Na’vi leaders known by the title Toruk Makto. AVATAR is not saying this proves Jake is the reincarnation of a legendary figure, a hero whose destiny it is to lead the Na’vi to victory; he is still just Jake. He simply takes on the appearance of the mythical hero, and that appearance (rather than the reality) is what makes the difference.

Second, AVATAR is a fantasy. Yes, it is dressed up in science fiction finery, but underneath, it is a fantasy. Unlike films that deal with some semblance of reality – like, say DANCES WITH WOLVES – AVATAR cannot reasonably be criticized for being “unrealistic.” It is under no obligation to present a believable, warts-and-all presentation of the good and bad aspects of primitive tribal life. We may recognize parallels between the Na’vi and Native Americans (even the name suggests a similarity), but the film is violating no truth by presenting an air-glossed view of its aliens.

In fact, one might argue that a large part of the reason for making a film about aliens (instead of one about Indians) is that it allows the filmmaker the latitude to avoid the messy complications and ambiguities of reality. Instead, it can reach for the mythical grandeur that can only by achieved when dealing with larger-than-life archetypes. Part of what makes Sully’s journey so moving is that he is not merely switching sides; he is ascending to a higher order of being, becoming something better than he was. Whether or not this is believable, it is tremendously moving, and Cameron knows how to milk it for the emotional impact that makes AVATAR more than a special effect spectacle or a simple slam-bang action movie – all while serving up as many special effects and as much action as you will see in any other blockbuster.

So, sure, in AVATAR, killing and gutting animals is presented not as a leftover bit of barbarism but as almost a religious rite. As an animal rights activist and a vegetarian, I object to sanctifying this sort of behavior, but as a viewer I see it as part of the film’s fairy tale nature, and let’s be honest – it’s not as if they animals being killed are real – or even look particularly real.

LIVING IN THE DIGITAL WORLD

For all the talk about technological advances, AVATAR’s motion-performance capture and digital effects create the same old glossy sheen we have been seeing for well over a decade, rendering the characters in terms that usually look beautiful but not always believable. This becomes immediately obvious when Jake first awakens in his Avatar form: lying on a bed in the human hospital, he resembles an over-sized cartoon pasted on top of the live action. Fortunately, this has the (perhaps unintended) side effect of removing the story one more step from reality and thus attenuating the questionable aspects of the storyline, which become part of the film’s fantasy world.

To be fair, the effects often do look quite realistic, but usually this happens when the Na’vi are seen blending into their native surroundings. Especially in close-up, with shadier lighting that softens the bright blue of their skin tone, Jake and the Na’vi do look as convincing as any actors in makeup ever did.

The computer-generated imagery assist Cameron in achieving something seldom seen in his previous films: true visual beauty. As a director, his strength has always been the muscular way he presented strong action-packed story lines, using the camera to capture the narrative and the pyrotechnics without ever displaying much in the way of recognizable vision. Admittedly, there were a few flashes in TITANIC (a drowning victim floating in a silent underwater ballet, dress billowing with a beauty that belies the sadness of the image), but in AVATAR, for the first time, Cameron presents a film loaded with breath-taking imagery that overwhelms the senses on an immediate, primal level, regardless of how it advances the plot. The miracle here is that Cameron achieved this pictorial beauty without falling into the trap of letting it overwhelm the story-telling; the balance creates a near perfect piece of audience-pleasing entertainment.

LOVE AND WAR

Part of that balance involves a love story – an element that has been a part of Cameron’s films since THE TERMINATOR (1984). Canny commercial filmmaker that he is, Cameron knows that women will patronize action movies if they are given some emotional anchor; however, he has gotten into trouble in the past when he pushed the love story more into the foreground. THE ABYSS’s death-and-resurrection scene – with Virgil Brigman refusing to give up on the apparently drowned Lindsey Brigman – pushed histrionics to the point of bathos; TRUE LIES combo of marital discord and anti-spy terrorist was a muddled mess. No one thinks TITANIC’s Romeo-and-Juliet storyline was the most well-written cinematic love story, but at least there Cameron had the wisdom to ground it in a real-life disaster that lent the love story a gravitas it otherwise would have lacked.

You always suspected – and dreaded the suspicion – that Cameron was pushing toward the day when he could abandon the action altogether and simply tell a love story. With AVATAR, for the first time, you start to view this possibility with anticipation rather than dread. The romance between Jake and Neytiri (STAR TREK’s Zoe Saldana) is engaging on its own terms, regardless of the anticipated third-act conflict.

But don’t fear, action aficionados; we have not reached that point yet. A large part of the reason AVATAR holds interest is that Cameron continues to abide by the rules of his unwritten contract with the audience. He knows that romantic subplots and thematic concerns can increase audience identification and heighten rooting interest, but he also knows how to use that identification and interest to involve you in the battle scene you know is coming. Sure, it’s heart-warming to see Jake fall for Neytiri; it’s even more fun to imagine right-wing pundits suffering an epidemic of exploding heads as they see their former favorite war-monger2 go all Al Gore on them, but in the end we know that our patience for sitting through the love story and pro-ecology talk will be rewarded with a big bang (well, many big bangs) in the third act.

If there is a weakness here, it is that Cameron seems oblivious to the subject of collateral damage. Yes, we enjoy seeing Jake and his comardes turn the tables on the invaders, and we want to see them destroy the enemy airships, particularly the big one targeting the Tree of Souls (the center of the Na’vi’s spiritual life). Unfortunately, the fact remains that the ship crashes and blows up in a mass of flames in the middle of the Na’vi’s beloved forest – a monumental piece of destruction that is shrugged off without interest. We’re simply supposed to cheer, not stop and think, “But wait a minute – what about all the trees and animals that just got torched down there?”

To his credit, Cameron uses the action to comment on current events. The felling of the Na’vi’s homeland may recall uncomfortable memories of 9/11. More interestingly, the battle between the technologically superior humans and the natives defending their homeland stirs up interesting ideas about the morality – or lack thereof – involved in occupying someone else’s land, without ever specifically referencing Iraq or Afghanistan.

If anything, Cameron does not go far enough in this direction. After the initial battle has been won by the humans, you might expect Jake to conclude that straight-foward conflict is a no-winner and instead encourage the Na’vi to engage in guerrilla tactics, hitting soft targets in night-time raids and causing so much trouble that the greedy capitalists eventually decide it’s not worth their trouble to stay.

That, however, is a long-haul strategy not conducive to a quick, slam-bang finish, so Cameron opts for more of a ZULU DAWN approach, with the primitive local relying on sheer numbers to outweigh their opponents’ technological advantage. (As an added plus to balance the two sides, the planet of Pandora itself seems to chip in, with the local fauna – some of it enormous and quite ferocious joining forces with the Na’vi; as cornball as it sounds, it works like a charm on screen – not only exciting but even tear-jerking.) The David-and-Goliath battle, with viewers rooting for the out-matched little guy fighting off the big, bad invaders, may stretch credibility, but we are so invested in the outcome that we believe it anyway. (It is also amusing to imagine, as I often did while watching the locals defeat the superior forces of the invaders, that Cameron had made the whole film simply to remind us of how ridiculously unconvincing is the final battle between the Ewoks and the Empire in RETURN OF THE JEDI.3)

CONCLUSIONS

With all this thematic quibbling, why does AVATAR work so well? Because in a very real sense, these details do not matter, except as fodder for after-screening discussion. While the film is unspooling on the screen, it holds you under its spell because, whatever his weaknesses as a philosopher, Cameron is a master filmmaker who knows how to manipulate the elements to involve the audience, and once you’re engaged in the story, small flaws become eclipsed by the emotional impact achieved through a combination of engaging characters and exciting action.

Cameron is aided here by strong performances. Worthington initially looks a little bland to play a lead, but this turns out to be a clever gambit; he’s a bit of a blank, an unknown, who grows on us as we get to know him better. Giovanni Ribisi and Stephen Lang give good turns as the insenstive corporate drone and his military enforcer, respectively; so much so that you almost wish Cameron had injected a little ambiguity into them, allowed at least a touch of sympathy. Sigourney Weaver is stalwart as Dr. Augustine; she works through the cliched arc of disliking Jake (the newcomer who has not properly trained for the mission) to respecting him while making it seem natural, not an obligation of the script. (I will continue to object to the Na’vi avatar of Weaver, however, whose thin frame and elongated limbs suggested an awkward teenager with even more awkward facial expressions.) And I must say it is nice to see Joel Moore graduate from the low-budget little-seen horror of HATCHET (2006) to a solid supporting role in a major nationwide release.

James Horner is back on board, providing the score, which is as big and bold as the images require. If the closing credits song suggests a deliberate reprise of TITANIC’s Oscar-winning formula (your ear keeps expecting Celine Dione’s voice to break through), well, at least this is the only time AVATAR falls prey to looking like an imitator that fails to match its enormous predecessor.

James Cameron faced a virtually impossible task: fashioning a follow-up to the biggest motion picture blockbuster of all time. Somehow, he succeeded, on both a critical and commercial level. AVATAR is too riddled with small imperfections to be reckoned a cinematic masterpiece; nevertheless, it is one of the most impressive science fiction films ever made. We may admire its glossy CGI and marvel at Cameron’s ability to beat the apparently unbeatable odds, but these are relatively minor achievements. What’s truly great about AVATAR is not that it’s a career achievement or a technological breakthrough. The real miracle is that we can forget all that baggage and simply enjoy it for the artistry visible on screen.

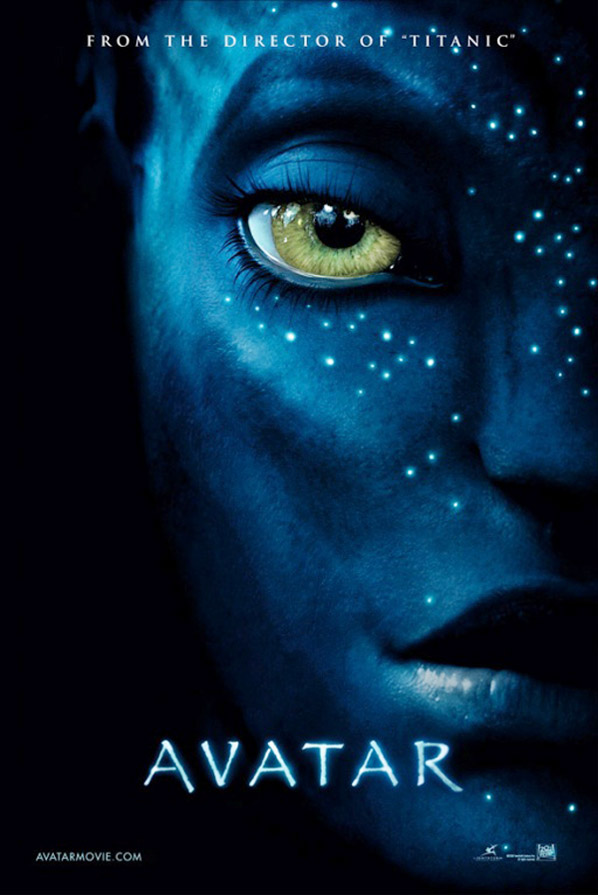

AVATAR (2009). Written and directed by James Cameron. Cast: Sam Worthington, Zoe Saldana, Sigourney Weaver, Stephen Lang, Michelle Rodriguez, Giovanni Ribisi, Joel Moore, CCH Pounder, Wes Studi, Laz Alonso.

FOOTNOTE:

- Cinema history is checkered in this regard. On one hand, there is Robert Benton, who followed up the Best Pic winner KRAMER VS. KRAMER (1979) with STILL OF THE NIGHT (1982), a failure in both box office and critical terms. On the other hand, there is Peter Jackson, who followed up LORD OF THE RINGS: RETURN OF THE KING (2003) with KING KONG (2005) – a film that made hundreds of millions of dollars worldwide, yet which was still perceived as a disappointment compared to the expectations it had generated.

- I’m probably not being quite fair to Cameron here. He’s not truly a war-monger, but despite giving occasional lip-service to anti-violent sentiments (as in T-2), his films portray armed conflict as being the best, quickest, and most effective way to settle a dispute. Even AVATAR, for all its ecological posturing, builds its plot around the basic assumption that negotiation and diplomacy are non-starters, on both sides; the only way to settle things is through battle.

- Some may question whether the reference to RETURN OF THE JEDI is intentional, but I suspect it is. AVATAR is loaded with similar references. Besides DANCES WITH WOLVES and JEDI, the Na’vi ride winged creatures that suggest The Dragon Riders of Pern, not to mention DUNGEONS AND DRAGONS. The concept of a primitive alien culture whose essence survives death by being absorbed into a plant-like network is lifted from George R. R. Martin’s novelette A Song for Lya. Cameron even lifts from himself; fortunately, he is clever enough to invert the repetitions, so this time we have the hero hanging off a missile on a jet plane rather than the villain as in TRUE LIES, and in the final face-off between an alien and a human in a mechanical exo-skeleton (a la ALIENS), we are rooting for the alien.

[serialposts]